Tim Burton on cancel culture and his Beetlejuice sequel: ‘I used to think about society as like the angry villagers in Frankenstein’

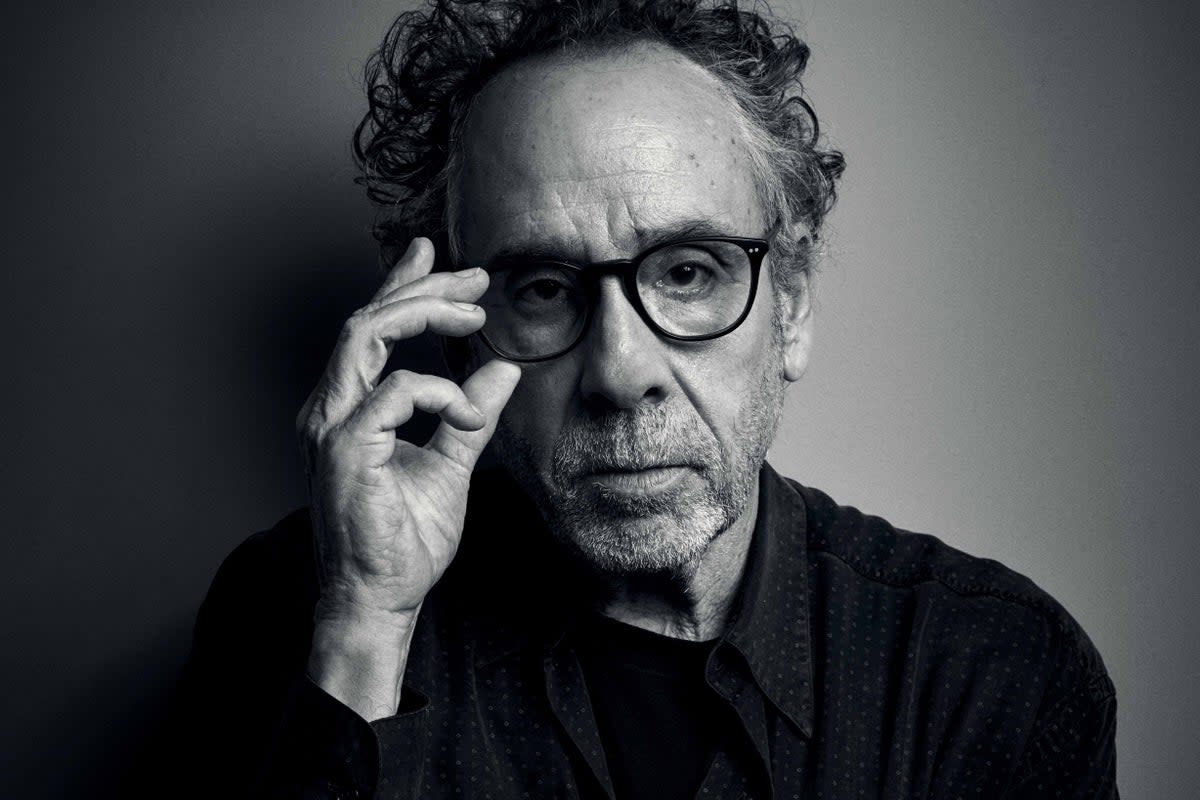

Tim Burton is waving, not drowning. The genius behind Edward Scissorhands, Corpse Bride and the Netflix hit Wednesday has an unusual approach to speaking to the press. He accentuates his remarks with extravagant, octopus-like rotations of his very long arms. He’s also polite, friendly, and as eccentric as one might hope. Talking to me by Zoom from what appears to be a small, dark room in his London home, he cuts a reassuringly gothic figure. He is dressed in black, his hair sticks upward (“A comb with legs would have outrun Jesse Owens, given one look at this guy’s locks,” Johnny Depp remarked after first meeting him), and he could still pass for an extra on a Universal horror film from the Thirties.

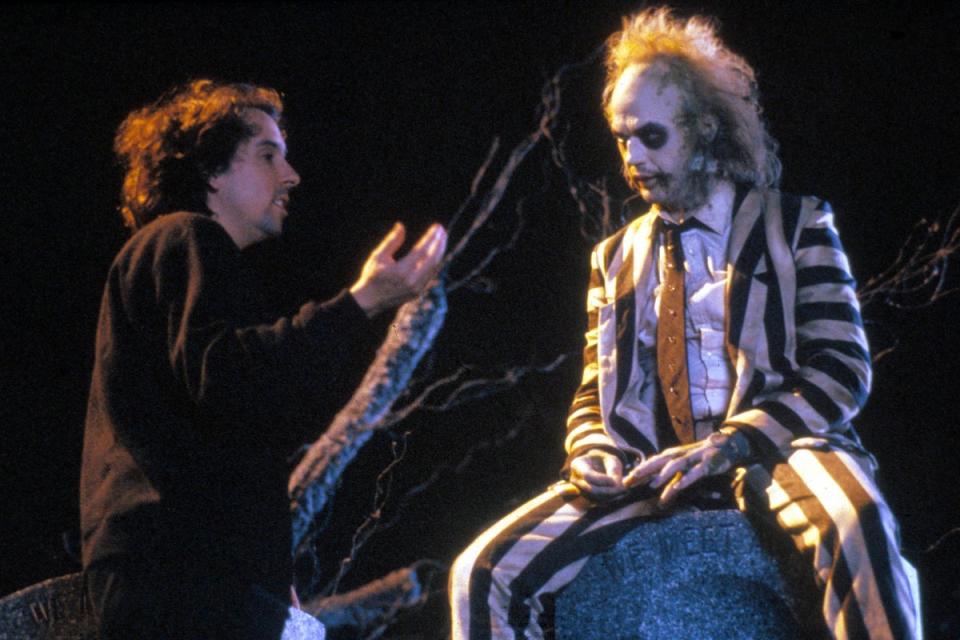

He has just had to down tools on his new movie, Beetlejuice 2, because of the Hollywood actors’ strike – a frustration given that he was less than two days away from completing shooting on the long-awaited film (which brings back Michael Keaton and Winona Ryder from the 1988 classic horror comedy).

Burton talks of trying to do the new Beetlejuice “in the same spirit” as the first film. Yet it’s not the only one of his old movies he has been thinking about recently. The filmmaker and artist strikes a wistful, melancholic note when remembering Paul Reubens (aka Pee-wee Herman) the anarchic comedian who died at the end of July. Reubens gave Burton his big break, hiring him to direct Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985). But the comic’s career was derailed after controversy in his private life involving pornography and drugs. Burton, however, always stayed loyal to him.

“I worked with him,” Burton says. “I had him in Batman Returns and he did some voices in The Nightmare Before Christmas. I’d always send him a Christmas card. And I did speak to him a few months ago. I talked to him for about 45 minutes... but I had no idea what his situation was.” (Reubens had privately been diagnosed with cancer.) The director had had “a weird idea” for a project on which they might have collaborated once more – but that obviously won’t happen now.

There’s a poignant moment at the end of Edward Scissorhands (1990) when the mob turns on the innocent young hero who has scissor blades for hands. I put it to Burton that the same thing has happened in symbolic fashion to the film’s star Depp and to Reubens, who both had very public falls from grace.

“Here’s the thing,” explains Burton. “When I was a child, I always had an image of the angry villagers in Frankenstein... I always used to think about society that way, as the angry village. You see it more and more. It’s a very, very strange human dynamic, a human trait that I don’t quite like or understand.”

The friendship between Burton and Depp once ran very deep. “He was a bit similar to me, kind of suburban, white trash, whatever – we connected on some kind of level,” the director told Deadline in 2022. Burton himself has never had to face the wrath of the public. He’s just turned 65, but his numerical age, it seems, works in reverse to how he’s always seen himself. “Listen,” he says. “When I was a child, I felt like Roderick Usher from [Edgar Allan Poe’s] The Fall of the House of Usher. I always felt old. I feel like I am kind of reversing in a way. When I was 10 years old, I felt like I was old and dying. In my mental state, I am reversing my process.” Burton sounds a Benjamin Button-like note, suggesting that he actually feels younger with the passing of the years.

They had AI do my versions of Disney characters... It reminded me of when other cultures say, ‘Don’t take my picture because it is taking away your soul’

He’s likely referring to the 1960 Roger Corman version of The House of Usher, in which Vincent Price plays Roderick, but the Poe story has always had a huge resonance for him. He once tried to adapt it for the screen, only updated to the California of his childhood, from a script by British playwright Jonathan Gems. That didn’t get off the ground – and now a rival Netflix version is being released next month.

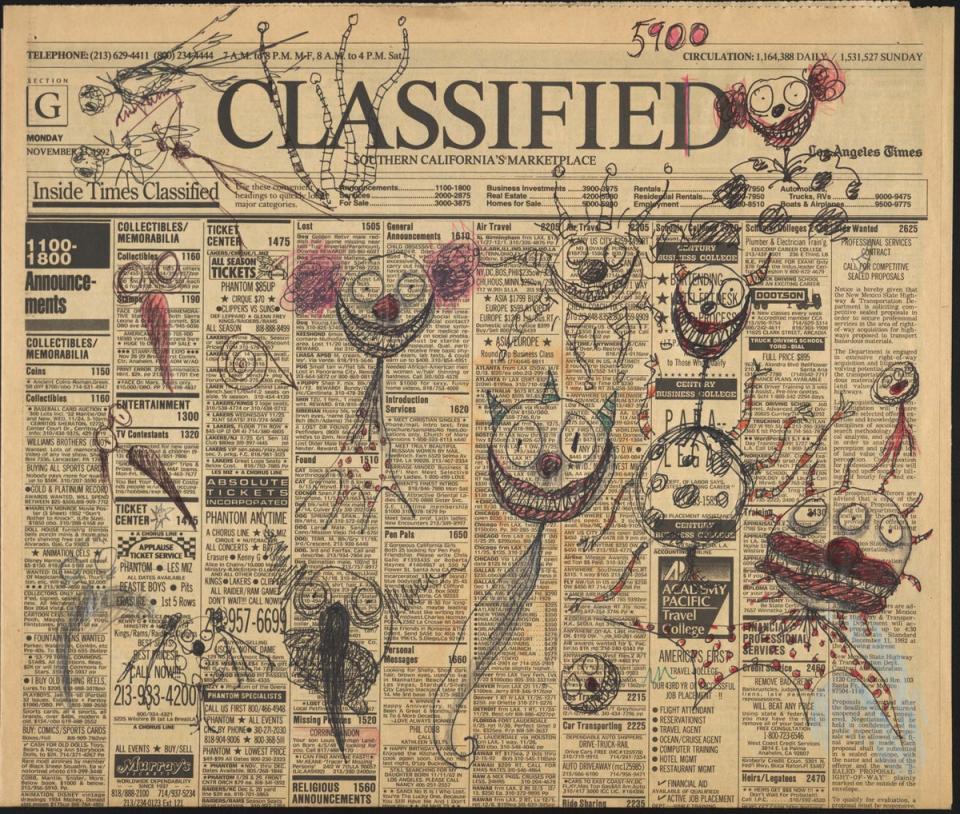

Burton, meanwhile, is getting ready for an exhibition of his sketches, paintings, drawings, photographs, concept art, storyboards, costumes, moving-image works, puppets and, who knows, maybe his toenails too, at the National Museum of Cinema in Turin next month.

The new show is described by the museum’s president Enzo Ghigo and its director Domenico De Gaetano as “a journey into the visionary universe and creativity of Burton”. It features a wealth of material from the filmmaker’s own personal archive.

So just what does Burton do with all those thousands of artefacts assembled from a career that now stretches back almost half a century and encompasses such modern-day classics as Ed Wood and the Keaton Batman movies? Does he keep the old bric-a-brac in drawers in his bedroom?

Burton laughs at the question. Back in 2008, when the Museum of Modern Art (Moma) in New York was first planning a similar exhibition (which eventually took place in 2010), he went searching for the material that he had left in drawers and boxes in his grandmother’s house. “I didn’t know where the hell the stuff was, but [the curators] spent a couple of years finding it all. I just finally realised I never threw anything away,” he says. “It’s kind of disturbing, but that is what happened.”

Now, he tries “to organise it a bit more... whether it’s drawings or things from films, it means a lot. I am now a bit better at keeping it and archiving it a bit more. But at the beginning, I was more of a hoarder, a pack rat. I guess I never threw anything away. I felt like I did, but I guess I didn’t!”

He’s all for exhibitions of his work like the ones at Moma and in Turin. “With the Moma thing, people went to a museum who never went to a museum, especially kids.” He hopes that many of the young visitors to the event in Turin will be inspired to draw, just as he still does every day.

He’s acutely conscious of the way that artificial intelligence poses perhaps a greater threat to animation than any other art form. It’s almost as if it’s coming after him personally. “They had AI do my versions of Disney characters!” the director exclaims in mock horror. “I can’t describe the feeling it gives you. It reminded me of when other cultures say, ‘Don’t take my picture because it is taking away your soul.’”

The AI-generated examples were created by Buzzfeed for an online feature. They included a Sleeping Beauty with a pale white face and long blonde tresses who is dressed in black and has stitches in her cheeks; a Pocahontas running through a Sleepy Hollow-like haunted forest; and a Snow White with jet black hair and ghoulishly big eyes. Burton acknowledges that some of them were “very good”. But that didn’t mean he enjoyed the experience of seeing his own artistry cloned and imitated. “What it does is it sucks something from you. It takes something from your soul or psyche; that is very disturbing, especially if it has to do with you. It’s like a robot taking your humanity, your soul.”

He refers to his work, whether drawing, writing or indeed making movies, as “a therapeutic thing”, a way of making sense of the world. As a kid, Burton was trapped in the suburban wilderness of Burbank in Los Angeles, the home of Disney Studios but not, as he has repeatedly made clear in scathing remarks in past interviews, an inspiring place for a would-be artist to grow up. “It could be Anywhere USA,” he told author Mark Salisbury, describing the town as “a blank environment”. He referred to Burbank as “the pit of hell” to another journalist. Nonetheless, later this month he will be returning there. The Burbank city council has declared that Sunday 24 September will be “Tim Burton Day”, and he’ll be back in his home town to accept a new “Visionary” award.

“Everything I’ve said I’ve meant,” Burton insists of all those withering observations he has made over the years about Burbank. “But at the same time, it’s where you’re from. Those experiences, living there and growing up there, shaped who I am. When I talked negatively, it was only from one side of my psyche. The other side is that I am from there, and if I hadn’t been from Burbank, I don’t think I would have been who I am. It definitely is a part of me, even though I don’t live there any more. It’s like anything. Nothing is only positive in your life.”

Burton sounds wary about the reception he’ll be given back in his home town. “Will they give me the key to the city? I don’t know...” he says, cautiously. “I went to my 10-year reunion in high school only because I didn’t really know anybody in high school. That was many years ago. I don’t think I know anybody in Burbank, I am not sure... we will see.”

Burton’s father, who worked for the town’s Parks and Recreation department, was a minor league baseball player. I ask if any of the Babe Ruth genes have come down to him. He doesn’t seem like a jock, but once broke his hand playing water polo and says that as a kid he had some sporting ability. “The way the newspaper article wrote it, it was like I was a star water polo player who was out for the season because of his broken hand, but I never recalled myself being that good... he [my father] had more of it [sporting ability] than I did. But I dabbled in sports, yes.”

In the end, though, he went down the artistic route, winning a scholarship to attend the California Institute of the Arts animation programme, which was sponsored by Disney. Pixar’s John Lasseter was a fellow student at CalArts. So were various other luminaries, such as the writer/director of The Incredibles Brad Bird, John Musker (of Moana fame), and Henry Selick (director of the Burton-conceived 1993 stop-motion feature The Nightmare Before Christmas), who all went on to become major figures in Hollywood animation. “It was an expensive school, and I couldn’t have gone there unless I had gotten a scholarship,” he says.

Burton waxes nostalgic about the days when he used to “wander around naked in the hallways”. The other students regarded those studying character animation as “geeks and freaks”, but he found many kindred spirits among his peers. “It felt like a bunch of slightly outcast people all put in together, which was nice.” He reminisces about the “camaraderie, rivalry, friendship, espionage and intrigue” between the students.

From CalArts, Burton made the jump to Disney. His colleagues there claim that once, after Burton had had his wisdom teeth out, he roamed around the offices with his gums still bleeding, pretending he was a vampire, dripping blood and saliva onto his fellow students’ desks. “It was a dramatic, Vincent Price-like, tortured hero statement,” Musker told me of the stunt. “I was following him around as he did this. He ultimately lost enough blood that they had to send him across the street to the hospital. He was about to pass out. It was kind of a stunt, but Tim played it totally straight. He wouldn’t break character.”

Is that true? “I have the pictures to prove it,” Burton insists. “I should have known early on that I had a troubled relationship with Disney. That should have been the first sign.”

Growing up, I always felt like a foreigner. When I went to London... I felt it was foreign but I felt comfortable there

How does he feel about Disney today? “I guess it’s like Burbank, only worse... it’s like a family. I can look back and recognise the many, many positives of working there, and all the opportunities I’ve had. I can acknowledge each and every one of those very deeply, and very positively. Equally, on the other side, I can identify the negative, soul-destroying side. As in life, it’s a mixed bag.”

On the positive side, Burton gained valuable experience working on films like The Fox and the Hound (1981), Tron (1982) and The Black Cauldron (1985), on which he was a conceptual artist. The studio gave him opportunities. It financed his early shorts Vincent (1982), about a kid who pretends to be Vincent Price, and the short version of Frankenweenie (1984), which he made into a stop-motion feature in 2012.

One way of escaping Burbank and Disney was coming to Europe. Burton ventured to the UK in 1989 when he recreated Gotham City at Pinewood Studios for his film version of Batman. Working with the visionary production designer Anton Furst and an army of technicians, he created one of the biggest sets ever built at a British studio. He didn’t shoot the 1992 sequel Batman Returns in Britain, but many of his subsequent films have been made on these shores. His home is still in Hampstead, he was married for many years to British star Helena Bonham Carter, and he can safely be described as an Anglophile.

“Where I came from, I felt like a foreigner. Growing up, I always felt like a foreigner. When I went to London... it was very strange. I felt it was foreign but I felt comfortable there. People were more eccentric. I don’t know, there was something about it,” Burton muses. He says that he now feels “very much at home” in England.

One paradox about Burton is that he is a sensitive, UK-based loner and yet he has successfully operated for many years within the Hollywood studio system, making huge-budget films. He has produced as well as directed his own movies. How has he thrived in such a brutal, Darwinian universe?

“Honestly, I don’t really know, because I am really not that good at talking or speaking or trying to sell something, so to speak. Looking back, it’s a very, very strange journey that I can’t quite explain.” He seems stumped by his own success.

Burton has often said that making a big studio movie is such an exhausting experience physically and emotionally that he is left wrecked at the end of it. He often vows that he will never do it again but, as time passes, he will always return to the fray.

“That’s why it is hard for me to watch the movies afterwards, because I still feel the emotional whatever of it. I don’t get a release from that. But I do enjoy all the people I’ve worked with. On this last one, Beetlejuice 2, I really enjoyed it. I tried to strip everything and go back to the basics of working with good people and actors and puppets. It was kind of like going back to why I liked making movies.”

The new movie not only brings back old favourites like Keaton, Ryder and Catherine O’Hara, but its cast includes Monica Bellucci (reported to be the director’s new girlfriend), Wednesday’s Jenna Ortega, and Willem Dafoe.

The film is due to be released next September, and Burton hopes to finish it as soon as the actors’ strike is resolved. “I feel grateful we got what we got. Literally, it was a day and a half,” he says. “We know what we have to do. It is 99 per cent done.” At this point, the arm-swinging stops as the interview is brought to a sudden end by the publicists. As he signs off on Zoom, Burton looks a little like one of the characters from his movies retreating into the darkness – a friendly, ghostly figure saying a final goodbye before he disappears.

The Museo Nazionale del Cinema in Turin presents THE WORLD OF TIM BURTON, the exhibition dedicated to the creative genius of Tim Burton, conceived and co-curated by Jenny He in collaboration with Tim Burton and adapted by Domenico De Gaetano for the Museo Nazionale del Cinema. For the first time in Italy, the exhibition will be on view at the Mole Antonelliana from 11 October 2023 to 7 April 2024

Yahoo News

Yahoo News