Titanic at 25: how James Cameron captured 1990s anxieties with pure golden-age Hollywood style

Titanic (1997) arrived as disaster films were experiencing a comeback. Compared to the apocalypses visited on the world in Michael Bay’s Armageddon (1997) or Roland Emmerich’s Independence Day (1996), sinking a single ship may seem like small fry.

But James Cameron’s film played on the same worries about humanity’s fragility in the face of overwhelming forces (and the hubris of our technological prowess) that many films of the 1990s were exploring.

And yet, despite using pioneering techniques (computer animated figures, virtual environments), Titanic structurally harks back to older models of film making.

For all the film shares with other late-1990s blockbusters, as well as disaster movies of the 1970s, the genres Titanic most aligns with are from decades earlier still.

Titanic’s cinematic catastrophe reflected the pre-millennium anxieties that abounded towards the end of the century, from millenarianism (the fear that the year 2000 would bring about the end of days) to more mundane worries about the millennium bug.

In his 2016 documentary, Hypernormalisation, filmmaker Adam Curtis interprets the spate of late 1990s Hollywood disaster films as a “dark foreboding” His memorable movie montage, set to Suicide’s Dream Baby Dream, of upturned faces gawping at oncoming obliteration does not include Titanic. But, the film’s Edwardian setting aside, it would have fit right in.

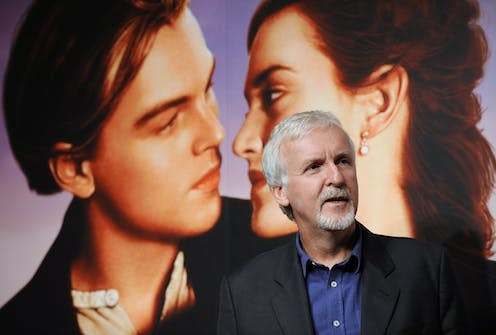

Titanic is explicitly structured as a microcosm of wider society. The story takes Rose (Kate Winslet) and Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio) to all ends of the ship, from the first class dining room, through steerage class in the lower deck, to the cargo hold and even the infernal engine rooms. James Cameron crammed a world into his giant floating metaphor – then sent it to its destruction.

The director had already considered the threat of worldwide apocalypse in his Cold War era Terminator (1984) and The Abyss (1989).

Despite the historical setting, Cameron imbues his film with the feel of epic science fiction. He wows audiences and characters alike with the technological marvel of Titanic, the ship and the film, as it heads towards its doom.

Yet for all of the movie’s end-of-millennium unease, the scale of Titanic’s production in its narrative, budget and run time most clearly recalls the roadshow pictures of the 1950s and 1960s. These blockbuster productions were designed to wring the maximum experience from films, deploying widescreen formats, new colour film processes, stereo sound and extensive spectacular visual effects.

Roadshow pictures encompassed historical and biblical extravaganzas, lavish broadway musicals and other grand productions. Charging premium ticket prices and playing exclusively in upscale theatres, they featured overtures and intermissions with run times designed to justify their expense.

Titanic’s runtime is over three hours, but the ship does not hit the iceberg until 90 minutes in. In this manner the film resembles such roadshow epics as the nearly three hour musical, The Sound of Music (1964). Though remembered as a film about the Von Trapp family fleeing the Nazis, it is – for the first half – a light musical comedy in which Nazis feature little beyond some mild foreshadowing.

The woman’s film and the final girl

Framing scenes set around modern exploration of Titanic’s shipwreck aside, Titanic’s first hour and a half largely foregrounds Rose, the teenage daughter of a wealthy American family.

Rose struggles against the oppressive expectations of her family, especially her mother. In this regard she initially resembles the heroine of the “woman’s film”, a “phantom genre” name coined by film critic Molly Haskell to describe those golden age films which aimed to appeal to the fears and fantasies of an adult female audience.

With its plot of escape from the cosseting of a traditional marriage (Rose chafes against etiquette, family duty, traditional gender roles and even her clothing) Titanic replicates the woman’s film for the first 90 minutes. That is, until Rose’s world is overturned – and then destroyed – by the slowly sinking ship.

This disaster transforms Rose into a version of what professor of American film Carol Clover calls the “final girl”.

More common to horror films, the final girl is the plucky tomboy who survives the onslaught wrought by the monster. She was an archetype familiar to Cameron, having co-created Sarah Connor for the Terminator franchise and Ellen Ripley for Aliens (1986).

In the path Titanic set for the technological, digitally powered film making that went on to dominate 21st century production, it looked forward to the new millennium. But with its subject matter, structure and archetypes, Titanic kept one watchful eye firmly in the past.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dylan Pank does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News