True story of Rochdale satanic abuse scandal as children taken from homes on Langley estate

A chilling tale of 'satanic panic' unfolded on a council estate in Greater Manchester, casting a long shadow over the community.

In the early hours of a May morning in 1990, a convoy of official vehicles ascended the hill from Middleton to the sprawling Langley council estate. Upon arrival, police officers and social workers descended upon five residences.

Children were abruptly woken up, hastily dressed, and whisked away amidst tears, as their bewildered parents watched helplessly. This marked the beginning of an unimaginable nightmare for six families who were accused by social service workers of participating in the satanic ritual abuse of children.

Approximately 20 children were taken into care, relocated to foster homes, and prohibited from any contact with their families, reports the Manchester Evening News.

For some, it would be a decade before they were reunited with their parents. Dave Edwards, a reporter for the Middleton Guardian at the time, recalled the events.

"The first indication we had that something was amiss was when a High Court injunction was served on the Middleton Guardian," he penned in 2006. "It was a list of names of individuals which the newspaper was forbidden from reporting on."

"Simultaneously, reports of the early morning raids began to surface, but initially, these were assumed to be drug-related operations. The local police remained reticent, directing us to the council, which was equally hesitant to provide any clarification."

"In those days, council committee meetings were conducted behind closed doors, and agendas and committee papers were classified documents. It was only when Langley councillor Kevin Hunt stormed into the office that the truth began to dawn."

Indeed, upon meeting councillor Kevin Hunt who presented a determined front, the unbelievable reality started unfolding. And the truth was that a form of modern witch-hunt was underway.

Akin to a contemporary witch-hunt, it soon emerged that something truly sinister was occurring. The families were accused of crimes so depraved they would have seemed far-fetched even in the most stomach-churning horror film.

They included killing babies, digging up corpses, and deliberately aborting foetuses as part of occult rituals involving their own children. Social workers were reported to be looking for crosses and wooden cages, long black robes and the remains of fires.

An example of the bizarre cross-examination the parents were subjected to is highlighted in this extract from an official transcript. In it, a police officer is questioning a father.

Q. X (his six year old son) has told us about things that happen to him during the night.

He says a ghost comes to him and after giving him sweets and lemonade he is taken somewhere else where, what I would say, weird things happen. What do you have to say about that?

A. I don't know what happens during the night. Only that we put him to bed.

Q. Do you know what Black Magic is?

A. No.

Q. Do you know what I mean by devil worship and cult meetings?

A. Sorry, no.

Q. What about capes and hood?

A. I have seen some of them on TV and video.

Q. This is the sort of thing we believe to be going on with your children.

A. Not in my house, we don't do no such thing as that.

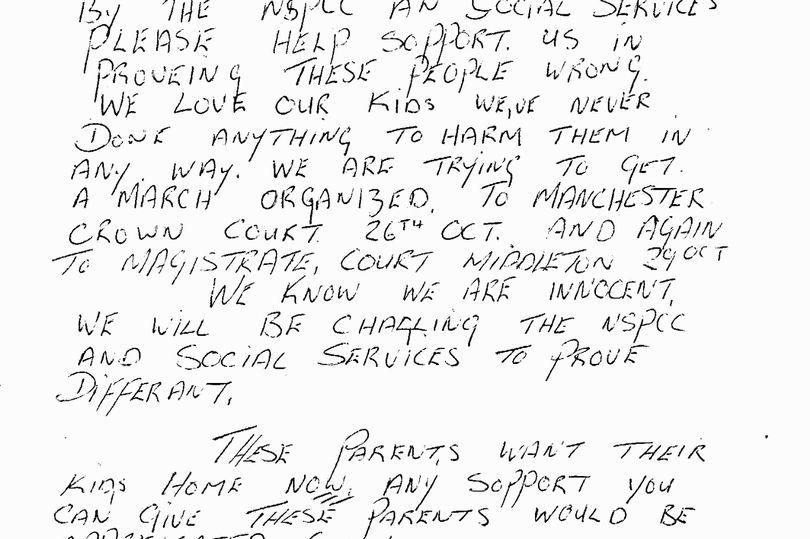

By September 1990, news of this scandal started appearing in national press and television platforms. The Mail on Sunday campaigned for the families, challenging the severe injunction against them.

The judge decided that, whilst day-to-day interaction with children and authorities was still banned, the press could interact with parents and share their stories. However, their children's identities had to be protected.

This case created international headlines. Many journalists and TV crews flocked to Langley, and the event was brought up in Parliament discussions. Under the title 'Satan's Garden Suburb', an article issued by the London Evening Standard painted Middleton as a hive of crime, sexual misconduct and substance abuse.

Despite heavy media scrutiny, authorities stood by their actions.

Gordon Littlemore, Rochdale councils director of social services, stated confidently during a press conference: "It is the view of social services and the police that the abuse the children describe is real and not the product of their imaginations, fuelled by watching video horror films."

He also praised the staff who handled these cases, "The social workers dealing with these cases are experienced and skilled in work with children. I have every confidence in their ability to deal with these sensitive matters."

However, not all were swayed by his assurance. Tony Heaford, ex-Mayor of Rochdale and a Langley councillor, was amongst the first individuals to voice doubts. At the time, he expressed his outrage, stating: "Families have been destroyed and those officials involved have barricaded themselves in the town hall, refusing to admit what they've done is a huge mistake."

"It's a disgrace. The lives of these innocent children and their parents have been irreparably ruined."

Steve Hammond, who was the editor of the Moston, Middleton and Blackley Express at the time, also had his reservations. In 2006, he wrote: "In various reports the two social workers most involved in the case said children had talked of ghosts, of being taken to haunted places, being dressed up and put in cages, chained to walls, seeing ghosts kill sheep and eat them, of killing pigeons, of killed babies."

"On the face of it, the parents of these children had committed acts that made the Moors Murderers look like minor offenders. So, we asked ourselves, what were the police doing? We were told in an off-the-record briefing by a senior officer on the local child protection teams that, basically, no arrests had been made and, that though inquiries were still being pursued, no arrests were likely to be made."

"This seemed to be a very crucial development. Would the police take the risk of failing to pursue a group of psychotic adults, addicted to Satanism and ritual murder? Of course not. These were the conclusions we reached, but they were conclusions that seem to escape social workers and council officials."

Even Barbara Brandolani, a white witch from Moston, had her doubts. She derided the reports as unfounded rumours, believing they were instigated by fundamentalist Christians in the United States where similar paranoia is ongoing.

Even amongst local clergymen, there was no consensus on whether Satanism was prevalent in Langley. While most stayed quiet on the issue, one clergyman took drastic action such as sprinkling holy water at bus stops and other spots frequented by the missing children.

The police, however, started distancing themselves from these assertions soon after. Greater Manchester Police's then Chief Constable, James Anderton stated: "A lengthy police investigation in respect of the children involved has not produced evidence to justify the institution of criminal proceedings."

Despite growing scepticism, the children remained in care. The case made its way to the High Court the following year.

On 11th March 1991, after a 47-day hearing, Mr Justice Douglas Brown declared that Rochdale social services had committed a 'gross error of judgement'. He directed that most of the children who were detached from their parents be immediately returned home.

The judge ruled that only four children, all from the first family that was raided, should remain in care but his decision had nothing to do with the allegations previously mentioned. In his judgment, the act of removing the children was termed as a 'lamentable start to a lamentable series of events'.

He opined that the interviews had been 'appallingly mishandled', asserting that information had been collected based on 'Chinese whispers' rather than factual evidence. The judge indicated that the fault heavily lay with an "unhealthy degree of professional single-mindedness" shown by the two involved social workers, pointing directly towards the senior social services department level. However, he believed that the social workers acted with 'good faith'.

Gordon Littlemore resigned the following day. In his statement, he noted: "Following criticism by the judges in the wardship case of the practice of the social workers, as chief officer of social service department I have today tendered my resignation, which has been accepted."

The press gag, in place despite the judge's ruling, barred families from sharing their own accounts. It took 15 years for this order to be lifted, following legal challenges from the BBC and the Middleton Guardian, preceding the broadcast of documentary 'When Satan Came to Town' and multiple articles revealing the true horror magnitude.

During the hour-long film, hosted by Fiona Bruce, a victim shared his ordeal of telling his teachers odd stories about ghosts, children caged, sheep slaughter and infant murders at age six. Such childhood imagination resulted in him and his siblings, his sister and two brothers being put into care.

The mum of these children openly expressed her fearfulness to the documentary team saying: "It frightened the life out of me." A glimpse of 1990 interviews involving the kids and social workers was also first-time shown during the documentary.

The children's insistence that they were unharmed was repeatedly dismissed during questioning. In one instance, a six year old girl was reduced to tears for 17 minutes as a social worker relentlessly questioned her.

In a 2006 interview with the Middleton Guardian, one victim recounted how, at the age of 11, she was taken out of her primary school class by social workers. Along with her three younger brothers, she was taken to Booth Hall Children's Hospital for a medical examination.

She recalled: "It was a terrible ordeal, they were looking for signs of sexual abuse. We didn't know what was going on and were frightened, especially because our parents were kept from us. We were under a lot of pressure from the council workers who kept insisting that they were bad parents and made us agree."

"They shoved us in foster homes and for nine months we were not allowed to see our parents. It was a nightmare. They even made me say I was interested in adoption, when all I wanted was to go home and be with my family."

However, despite the full extent of the scandal now being public knowledge, one former journalist, who reported on the story when the injunction was lifted in 2006, said it did little to alleviate the pain.

Speaking anonymously, she stated: "It was this great unspoken thing that very much still lingered over Langley and Middleton."

"I think because of the history of Langley and its geography, being out on the edge of town, there was a lot of suspicion and distrust of the authorities and a lot of historical anger. There was a deep sense of people having been wronged. There was frustration that they hadn't been able to get justice."

"I spoke to one of the survivors who had moved away to Bolton and started a new life. The thing that struck me was that all those years later he was still frustrated that no-one listened to him.

"Even after the injunction was lifted and the full story was finally told, from my perspective it didn't feel like there was a sense of celebration or relief that finally everybody knew what had happened."

"It felt more like 'So what? What have we achieved? ' The pain was still there."

Fast forward 15 years, as the aftermath continued in Langley, another child abuse scandal was about to unfold around six miles north at Rochdale council.

At Knowl View special school in Bamford, dozens of boys were sexually exploited by men, including former Rochdale MP Cyril Smith. The school would later be described as a 'sweet shop for paedophiles'.

The connections between the two cases were scrutinised during the 2018 Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse hearings, when it was suggested that the errors made in Langley led to Rochdale social services being 'over-cautious' about intervening at Knowl View.

However, Richard Scorer, head of abuse law at Slater Gordon, who represented five Langley families in their civil action against Rochdale Council and several Knowl View victims, strongly rejects that theory.

"Everything was the wrong way round," Scorer told the Manchester Evening News. "You had social workers taking these children away from their parents in Langley in actions which were later found to be completely unjustified at the same time they were ignoring the scandal at Knowl View.

""They didn't take the massive issues at Knowl View seriously, but they were concocting this theory of satanic abuse. "I don't believe Langley was the reason they didn't act on Knowl View.

"The reality was the problems at Knowl View had been building for quite some time. "I could see the argument that they were more cautious about taking children into care, but I don't see that would constrain them from dealing with what was happening at Knowl View.

"What you had during that period was total dysfunctionality in social services and in politics in Rochdale. "He added: "It was devastating for the families.

""The children were taken away from their parents in these traumatic dawn raids, and spent differing periods of time away from families. ""There is a danger, however, that if a council has been through an experience like Langley they could become too cautious in taking action against abusive parents in future.

"Perhaps that means they could make the wrong calls the other way as well as making the wrong calls by wrongly taking children away. It would mean, its suggested, that other children may get left at risk. ".

Reflecting on the scandal now, Sara Rowbotham, Rochdale council's deputy leader and Middleton councillor, suggests while strides have been made to learn from past errors, there's much room for improvement.

Coun Rowbotham, renowned for revealing the Rochdale grooming gang during her tenure as a social worker, commented: "I would like to think that our approach to vulnerable families has moved on significantly."

"I would hope that new generations of social workers come in knowing that that approach is wrong, that it's abusive and intrusive."

"But at the same time I worry about survivors. Given our history in the borough what are we doing to help survivors? Are we the gold standard of working with survivors to help them get to grips with the abuse they experienced? ""I don't think we do as well as we could with that."

Yahoo News

Yahoo News