Trump Copies New Orleans’ Tragic 1853 Yellow Fever Playbook

After two weeks of skyrocketing coronavirus cases, Orleans Parish—the Louisiana county that includes the city of New Orleans—on Friday recorded the highest per capita death rate in the U.S. from COVID-19, according to The Times-Picayune/ The New Orleans Advocate.

With 997 cases and 46 deaths (more than half of the state’s total fatalities) reported by health officials, the city where jazz began has seen deaths surge to 11.76 deaths per 100,000 people, almost twice that of the second highest ranking American county, Richmond, which includes Staten Island, N.Y. with 28 mortalities.

The news came five days after Gov. John Bel Edwards starkly warned that Louisiana was on a trajectory as bad as Italy’s and issued self-distancing and quarantine orders for the state, as New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell had already done in the city. Edwards’ appeal to the White House for the declaration of Louisiana as a disaster zone bore fruit on Thursday, clearing the way for federal assistance.

As warm weather settles over this tropical city, and people huddle as social distancing sets in, the chilling hindsight shared by public officials and researchers is that the coronavirus rolled through the three-week Mardi Gras season of parades, balls, concerts and dawn-rocking parties which culminated Feb. 25, leaving a trail of human damage which the grim daily data belatedly now reflect.

New Orleans is no stranger to epidemics. Yellow fever ravaged the city throughout the 19th century. Some years were particularly bad, and 1853 was the worst, when yellow fever killed 8,647 people out of a population of 116,000. Although public knowledge of the virus’s cause, and cure, lay far in the future, a big part of the mortality rate could be blamed on the city’s leaders, who for decade after decade, epidemic after epidemic, persistently ignored the known benefits of street sanitation, proper drainage, and clean water. The mosquitos that carried the virus never had to look far to find a home.

The Pandemic Is Too Big for Trumpworld to Spin

The Crescent City’s current crisis was not hatched here, but the cyclical nature of human folly, embodied by President Donald Trump, registers in the jaded indifference to a virus in its early stages and a refusal to heed medical experts or respect empirical science until the crisis crashed into America, matching the political mindset that so damaged New Orleans in the 19th century. The difference, of course, is the enormous scale of human suffering.

“We have the greatest experts in the world,” President Trump boasted on Feb. 26, having previously said, “The virus will not have a chance against us.” But on Feb. 10, 16 days earlier, just before the World Health Organization (WHO) labeled coronavirus a global health emergency, the Trump administration sent its 2021 budget to Congress with a 16 percent cut in funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Trump’s war on scientific truth is the chief contagion of the yahoo politics spread by the Republican Party, Fox News, and the “alternate facts” machine of media mendacity. Fueled by a Christian triumphalist worldview hostile to scientific research they deem at variance with scripture, this movement and The Chosen One [as Rick Perry calls Trump] have systematically ignored or destroyed outright scientific expertise throughout federal departments and programs.

Last year, the Trump administration killed a USAID program called PREDICT, which for 10 years had tracked animal-borne, or zoonotic viruses with pandemic potential—in other words, viruses identical or similar to coronaviruses, which are common in people and animal species including camels, cattle, cats, and bats, the presumed source of the global outbreak “from an animal reservoir” in China, according to the CDC. ABC News reports that the program identified “nearly 1,000 new zoonotic viruses” transmitted to people. Programs like this are a cutting edge in thwarting epidemics and developing vaccines.

A month ago, as Italy followed China into quarantine and U.S hospitals and clinics faced epic uncertainties without testing kits, Trump tweeted, “The Fake News Media and their partner, the Democrat Party, is [sic] doing everything within its semi-considerable power (it used to be greater!) to inflame the CoronaVirus situation, far beyond what the facts would warrant.”

What the facts warrant is that we should salute people like Rear Admiral Tim Ziemer, a global health expert who, in 2018, as a National Security Council member assembled a team of infectious disease and public health experts to forge a policy with other agencies for emergency preparedness on biological warfare and epidemics—like COVID-19, the disease caused by coronavirus. But John Bolton, then Trump's National Security Adviser, sacked Ziemer and disbanded the group. Admiral Ziemer’s position is still vacant.

“Firing Zeimer was a stupid thing to do,” says Dr. William F. Bertrand, Wisner, professor of Public Health at Tulane University, an epidemiologist with long experience on response to AIDS and Ebola in Africa. “We need to know the threats of potential disease. I worked with some of the people in [Ziemer’s] group. The planning was based in part on the Famine Early Warning System I helped develop in the 1980s—a surveillance system for famine that looked at agricultural and meteorological data to the point where we can now predict mosquito outbreaks. We don’t know why influenzas slow down in summer; but you get the kind of protection that wasn’t there in yellow fever epidemics.”

In 1853 New Orleans was a booming port, the fourth most populous U.S. city, with 116,375 people, and America’s largest slave market. Rich northerners came south, building white-pillared mansions upriver from the French Quarter. The clannish white Creoles disdained arriviste Anglos settling in today’s Garden District.

New Orleans was a city of migrants, a crossroads of different colors, different tongues. Roughly a quarter of them were Irish immigrants who had come to the U.S. to escape their famine-hit homeland. But the city's social elite shared a jaded civic ethos, averse to helping newly newcomers by paying for adequate public services. The wretched system of sanitation for streets and water had dire consequences.

Yellow fever is an arbovirus spread by a mosquito, Aëdes (Stegomyia) aegypti, which carried the pathogen from African primates, infecting people. The virus spread on ships, particularly those carrying the enslaved to New World plantations. “The female of the species needs the protein found in human blood to ovulate,” Benjamin H. Trask writes in Fearful Ravages, a history of yellow fever in Louisiana. “After the virus has spread and incubated in the mosquito for a couple of days to a few weeks, the mosquito can infect other humans for the rest of [its] short life.”

The worst epidemics hit warm-weather ports where the insect thrived, such as Charleston, Mobile, and—worst of all—New Orleans. An NIH study estimates that 100,000 to 150,000 people died of yellow fever in America in an era before sophisticated data tabulation.

The yellow fever virus assaulted New Orleans in waves: as one crashed down, the impact receded, a few years on another hit with lethal force. The first epidemic, in 1796, killed 638 people out of 8,756, according to historian Laura D. Kelly. During the century that began in 1800, the epidemic hit in 67 summers, the worst years being 1847, 1853, 1854-55, and 1858.

New Orleans was vulnerable because of its wretched street sanitation and compromised water supply, allowing stagnant patches for festering mosquitoes.

The poor were yellow fever's principal victims, but no one was immune. In the summer of 1804, shortly after William C.C. Claiborne took office as Louisiana's first territorial governor, both his wife and 3-year-old daughter died of yellow fever, as did the governor's secretary. Claiborne too was stricken with the hacking coughs, hard vomiting, exhaustion, chills, and jaundice, but survived. He remarried two years later, but in 1808 his second wife also fell prey to the virus.

By mid-century, several physicians suspected moisture and crowded ships as a cause of the fever but had no proof. But while the health benefits of public sanitation were an acknowledged fact by that time, poor neighborhoods still endured unpaved streets, where pigs and mules died in the muck after heavy rains, and street-cleaning jobs were merely patronage lard in a municipality of scant oversight.

Why was city government resistant to infrastructure maintenance? “Many of the civic and commercial elite were acclimated—they had survived bouts of yellow fever,” Stanford history professor Kathryn Olivarius, author of the forthcoming Necropolis: Disease, Power and Capitalism in the Cotton Kingdom, told The Daily Beast.

“They didn’t care about immigrants shoved into this terror. They saw water pumps and quarantines as expensive, a drag on the economy. They would have to pay more in taxes. They had come to the conclusion, very mercenary, that public health was private acclimation—you either survived or avoided getting the virus. In 19th century New Orleans, if you got yellow fever, you had a 50-50 chance of surviving.”

Data on the fever death rates were flawed, understating the threat, says Olivarius. “Science, quote-unquote, was a great trump card for slaveowners to tell northerners, you don’t know the climate here or our needs. We require black slavery as a tool of public health. It distances white people from labor and spaces that would kill them.”

Reflecting that mindset, newspapers downplayed the fever deaths as those rose in June 1853. The Daily Crescent called yellow fever “an obsolete idea in New Orleans.” With 204 fever-attributed deaths in the week ending June 16, the Orleanian reported “no prevalent diseases or epidemics.” But the living saw people dying before their eyes. Death hit particularly hard among Irish and German immigrants in swollen tenements.

On July 25, Mayor A. D. Crossman urged the city’s aldermen to provide emergency funds for a board of health. After more delays, with 100 people a day dying from the outbreak, the aldermen approved $10,000 for the health board—and then left town en masse, joining the exodus of people with the money to pack off to the Gulf Coast, Grand Isle, or upcountry woodlands.

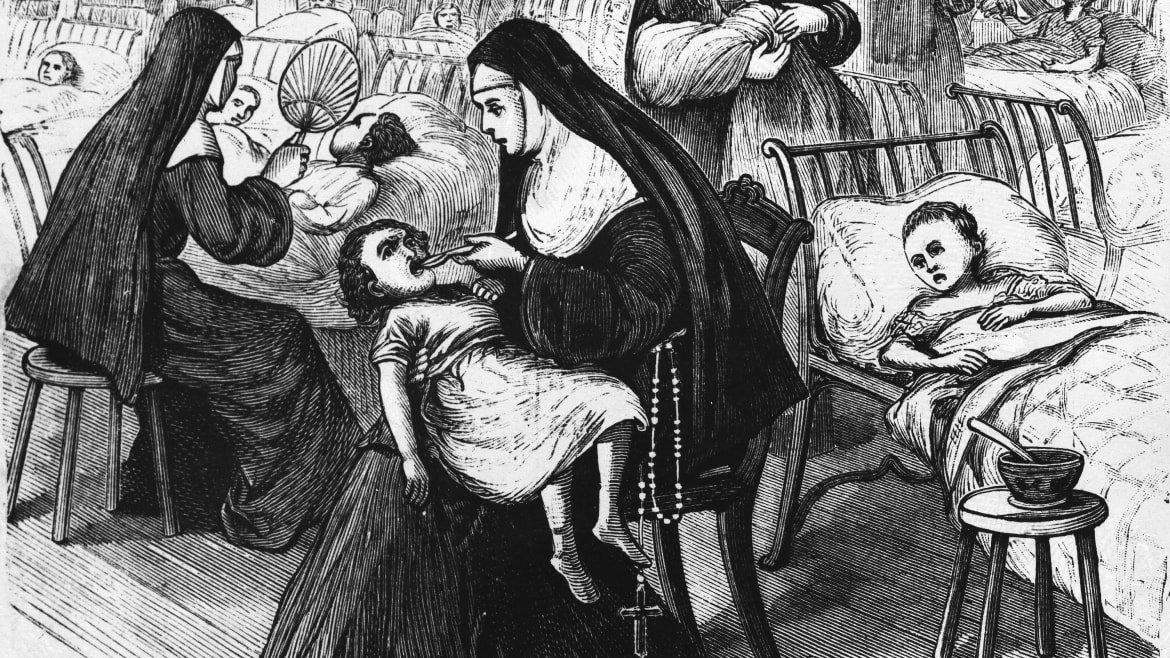

Sisters of Charity nuns worked heroically at Charity Hospital, where people lay in beds writhing with chills, throats hacking, vomiting black bile, spewing germs as they died. Cots jammed hospital halls; makeshift infirmaries opened in the local prison, insane asylum, and the Globe Ball Room, where a band played and people danced across the room from cots where people lay dying.

In the last week of July, 692 people died, including nurses, nuns, and 15 clergymen who had been ministering to the sick. In August, 4,844 people died, a staggering 4.3 percent of the population. Buggy hearses followed marching bands playing dirges, while mourners in carriages pulled up the rear. A Daily Crescent writer described cemeteries with “the odors of rotten corpses, exposed to the heat of the sun, swollen with corruption, bursting the coffin lids… What a feast of horrors! Corpses piled in pyramids!”

Sweat-lathered grave diggers wore nose-bags of camphor and spices to blunt the stench and keep from losing their wits. As a forerunner of today’s jazz funeral, the marching bands played cheerful melodies as they departed the macabre graveyards, back to life in the city. The Daily Picayune objected to upbeat music at funerals because the music preyed on “the nerves of the sick, whose homes are passed in every square, if not in every house.”

That fall, after the worst of it, the city got back to work, but the civic ethos did not change. The elite could always flee if need be. In 1861, Union troops occupying the city performed widespread street cleaning that halted outbreaks for several years (the formation of the federal sanitation commission during the Civil War was one of the high points in the history of public health in this country). But another epidemic hit in 1878 and claimed at least 4,046 lives. It would take a quarter of a century before Army surgeon Dr. Walter Reed pinpointed the mosquito as yellow fever’s source in 1900 and modern sanitation projects began eradicating the virus in America.

Donald Trump echoed those old New Orleans newspapers in initially downplaying the serious threat from the virus, until the intractable reality caught him blind in the headlights of truth. But again, Trump’s conversion to some semblance of reality may have come too late. By pandering to Christian extremists, by appointing who knows how many unqualified zealots to wreak havoc in federal health and science agencies that have historically relied on empirical research unfettered by ideology, Trump has put the nation in the sort of jeopardy that no emergency response can easily repair any time soon.

“When Christian Right leaders feel that scientific theories or practices are threatening their strongly-held beliefs, they attack the offending sectors of science with paranoid-style conspiracy theories,” writes sociologist Antony Alumkal in Paranoid Science: The Christian Right’s War on Reality. When you put those people in power, as Trump has done, you only invite the sluggish and catastrophic government response we’ve witnessed so far.

Trump is scrambling to get favorable coverage, as his medical advisers stand behind him at news briefings, trying to suppress signs of embarrassment at his wild statements while he tries to showcase a new image: he’s in charge, willing to send each of us money to get through the hard stretch. But the damage from his addictive mendacity and sacking government scientists has been done. He blew the chance to prepare us for this national nightmare and now he's using prime time news conferences in an attempt to blunt the impact of nightly news programs broadcasting information he doesn’t like. Just as the long-ago New Orleans leaders shunned projects to improve sanitation, so the Trump administration’s war on science, couched in the delusional “deep state” threat, is a virus hurting America at a time when we most need well-funded local health systems and federal departments with the best scientists to respond to the escalating crisis without fear of offending the Chosen One, and to remind us that once we were a country that sent people to the moon.

------------------------------------

Jason Berry is finishing a documentary film, using burial traditions as a narrative lens, based on his book, City of a Million Dreams: A History of New Orleans at Year 300 [2018]. Watch the section on yellow fever here.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News