Trump Leans Into an Outlaw Image as His Criminal Trial Concludes

Over the past week, Donald Trump rallied alongside two rap artists accused of conspiracy to commit murder. He promised to commute the sentence of a notorious internet drug dealer. And he appeared backstage with another rap artist who has pleaded guilty to assault for punching a female fan.

As Trump awaits the conclusion of his Manhattan trial — closing arguments are set for Tuesday and a verdict could arrive as soon as this week — he used a weeklong break from court to align himself with defendants and convicted criminals charged by the same system with which he is at war.

Sign up for The Morning newsletter from the New York Times

The appearances fit neatly into Trump’s 2024 campaign, during which he has said he is likely to pardon those prosecuted for storming the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, and lent his voice to a recording of the national anthem by a choir of Jan. 6 inmates.

There was a time when so much confirmed and alleged criminality would be too much to tolerate for supporters of a candidate for president, an office with a sworn duty to uphold the Constitution. That might have been especially true in the case of a candidate who has been indicted four times and stands accused of rank disregard for the law.

Yet with less than six months until Election Day, Trump, who has long pushed messaging about “law and order,” is leaning into an outlaw image, surrounding himself with accused criminals and convicts.

“I don’t think people appreciate the degree to which Trump has embraced the image of lawlessness in this campaign,” said Tim Miller, a former Republican strategist who worked for Jeb Bush’s presidential campaign and has been deeply critical of Trump.

Miller described Trump’s recent guest appearances as “a vetting decision that would have been unthinkable in past campaigns.”

Aides to Trump did not respond to an email seeking comment about what message he intended to send with these appearances.

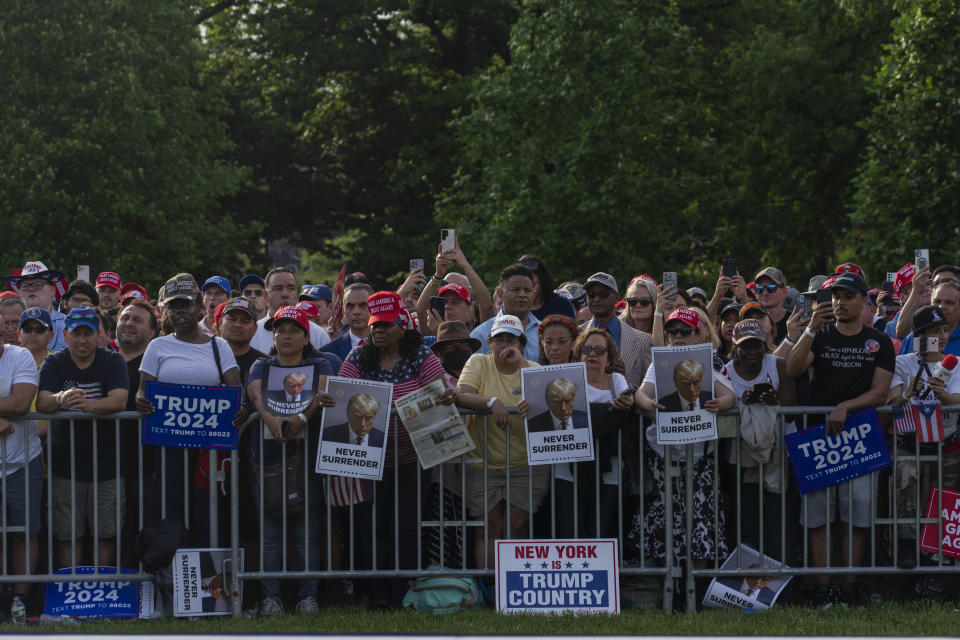

Trump’s rally last week in the Bronx wound down with appearances from the two rappers, Sheff G and Sleepy Hallow, whose real names are Michael Williams and Tegan Chambers. Both were charged in a conspiracy that Brooklyn prosecutors say led to 12 shootings. Williams also faces two counts of attempted murder. Both men pleaded not guilty and are out on bail.

Trump, from the rally stage, presented the two men to the crowd for a brief comment. Chambers kept his message short and to the point: “Make America great again.”

Two days later, as Trump spoke to an unfriendly crowd at the Libertarian Party’s national convention in Washington, he promised to commute the sentence of Ross Ulbricht, the founder of the black-market website Silk Road, who was sentenced to life in prison in 2015. At the same event, Trump took a photograph with the rapper Afroman, whose real name is Joseph Edgar Foreman and who pleaded guilty in 2015 to punching a woman attending one of his concerts.

In the courtroom, Trump has surrounded himself with allies turned defendants. The week that his former fixer, Michael Cohen, was set to testify that Trump had approved a plan to pay off a porn actor and cover it up, Trump marched into court accompanied by his indicted top legal adviser, Boris Epshteyn, who has attended every day of the trial since his own charges arrived in an Arizona election interference case.

Also in Trump’s entourage during Cohen’s testimony were Bernard Kerik, a former New York City police commissioner who spent time in prison on fraud charges and whom Trump pardoned, and Chuck Zito, a former actor who spent years in federal prison and was a leader of a Hells Angels chapter in New York.

Trump has insisted that every investigation into him is political, the work of opponents conspiring against him. He has tarred various representatives of the legal system — political candidates who campaigned aggressively against him and prosecutors appointed to investigate him — with the same brush, while backing his most controversial supporters.

This reflex of Trump’s — to ignore accusations if the accused is useful to him — is not new. But the scale has changed.

In his 2016 campaign, Trump put Elliott B. Broidy, a financier who had pleaded guilty seven years earlier to bribing New York officials, on his fundraising committee. It was a little-noticed move that might have raised more eyebrows had Trump not been smashing one norm after another as the presumptive Republican nominee.

Shortly after the election, Trump and his campaign were ensnared in an investigation into whether his political operation had ties to Russians. Several advisers were swept up in that inquiry, including his national security adviser, Michael Flynn; his campaign chair, Paul Manafort; his longest-serving adviser, Roger Stone; and Cohen, his fixer and personal lawyer.

Trump, who denounced that investigation as weaponized, repeatedly attacked Cohen after he pleaded guilty to a range of crimes including a campaign finance violation that he said was at Trump’s behest. But the president ultimately pardoned Flynn, Manafort and Stone, part of a wave of pardons and commutations in his final weeks in office.

Trump also granted clemency to people like Jonathan Braun, a Staten Island man with a history of violent threats who at the time was being pursued by federal officials for his work as a predatory lender. Braun used a connection to the family of Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, as he sought clemency.

Earlier in Trump’s presidency, he commuted the sentence of Rod Blagojevich, the former Democratic governor of Illinois. It was a move that some Republicans opposed, but Trump proudly had Blagojevich at a recent Republican National Committee fundraiser in Florida.

Trump’s efforts to remain in office and thwart the transfer of power resulted in multiple investigations into him and his allies.

The people indicted in those inquiries include Trump’s personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani; his White House chief of staff, Mark Meadows; his current top legal adviser, Epshteyn; his legal adviser Jenna Ellis; and a former Justice Department official, Jeffrey B. Clark.

Two other Trump advisers and allies, Steve Bannon and Peter Navarro, were convicted of contempt of Congress for defying subpoenas to cooperate with the House investigation into the former president’s efforts to stay in office.

Trump’s most recent behavior took place against the backdrop of his lawyers’ arguments before the Supreme Court that he is immune from prosecution in the federal case over his efforts to overturn the 2020 election. On social media, Trump has insisted presidents should have “absolute immunity.”

Despite arguing that he was acting within his rights, Trump has turned his criminal charges into a commodity. He sells campaign merchandise featuring his mug shot from his indictment in Georgia and aggressively raises money off claims that he is being persecuted.

One of the campaign’s recent fundraising efforts has focused on Trump’s false claims about the FBI search of Mar-a-Lago, the members-only Florida club that serves as his residence, in August 2022. The search came after he defied a grand jury subpoena requesting the return of any classified documents still at his home.

But the former president has baselessly argued that the FBI was trying to assassinate him, playing off standard language used in an operations order for the search, which was recently unsealed as part of a defense motion.

Prosecutors recently asked the judge overseeing the documents case to change Trump’s conditions of release by barring him from making any further remarks that could endanger federal agents working on the case. In response, the Trump team accused them of “unsupported histrionics” and demanded sanctions against them.

“He either does not know the truth, which is reckless, or he knows the truth and lied about it, which is abhorrent,” Chuck Rosenberg, a former U.S. attorney and FBI official, said of the standard procedures that Trump has misrepresented.

“He cares very much about wielding power, but not in service of some greater good,” Rosenberg said. “Rather, he wants power — including over the Justice Department — to benefit himself and his friends, and to harm others. He sees that power as only appropriate in his hands. That is a wretched corruption of what the rule of law means — and ought to mean — in this country, and it is deeply dangerous.”

c.2024 The New York Times Company

Yahoo News

Yahoo News