The Truth Behind Claims Black People Couldn't Buy Vanilla Ice Cream Under Jim Crow

We often encounter history repeated as folklore and vice versa. Firsthand encounters are retold so often, details get lost or rewritten in the process. One particular claim made its way from oral and literary retellings to the internet: that Black people living in Jim Crow South couldn't have vanilla ice cream except on the Fourth of July.

Why Vanilla Ice Cream?

The claim has gone viral on TikTok, and numerous articles have circulated versions of it for several years. As to why Black people were denied this flavor specifically, social media users presented numerous theories. A viral 2023 TikTok post with more than 2 million views said vanilla ice cream was "a privilege that some white Southerners didn't believe Black people deserved to have."

Another post on TikTok claimed, "It was seen as pure and for white people only during slavery and after through the Jim Crow segregation era." The same post connected Black people's love of butter pecan ice cream as having grown out of necessity and accessibility — pecans were reportedly native to the South and in the absence of being able to get other flavors, Black communities gravitated toward it.

Other TikTok posts highlighted the irony of the development of vanilla ice cream — it became possible due to the ingenuity of an enslaved Black boy named Edmond Albius from the French island of Réunion. In 1841, he discovered a method to hand pollinate the vanilla bean that became used worldwide.

Historical and Oral Accounts

Many examples of Black people being denied vanilla ice cream emerged from family lore and memoir.

Maya Angelou's 1969 memoir "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings," detailing her life as a child in Stamps, Arkansas, documented one such instance of discrimination through secondhand accounts. She wrote: "People in Stamps used to say that the whites in our town were so prejudiced that a Negro couldn't buy vanilla ice cream. Except on July Fourth. Other days he had to be satisfied with chocolate."

Writer Audre Lorde discussed her childhood summer trip to Washington, D.C., in her autobiography "Zami: A New Spelling of My Name." In a passage titled "The Fourth of July," she described being denied vanilla ice cream at a white establishment:

Two blocks away from our hotel, the family stopped for a dish of vanilla ice cream at a Breyer's ice cream and soda fountain. Indoors, the soda fountain was dim and fan-cooled, deliciously relieving to my scorched eyes.

Corded and crisp and pinafored, the five of us seated ourselves one by one at the counter. There was I, between my mother and father, and my two sisters on the other side of my mother. We settled ourselves along the white mottled marble counter, and when the waitress spoke at first no one understood what she was saying, and so the five of us just sat there.

The waitress moved along the line of us closer to my father and spoke again. "I said I kin give you to take out, but you can't eat here. Sorry." Then she dropped her eyes looking very embarrassed, and suddenly we heard what it was she was saying all at the same time, loud and clear.

Straight-backed and indignant, one by one, my family and I got down from the counter stools and turned around and marched out of the store, quiet and outraged, as if we had never been black before. [...]

The waitress was white, and the counter was white, and the ice-cream I never ate in Washington, D.C., that summer I left childhood was white, and the white heat and the white pavement and the white stone monuments of my first Washington summer made me sick to my stomach for the whole rest of that trip and it wasn't much of a graduation present after all.

Culinary historian Michael Twitty wrote about his father's experience being denied vanilla ice cream in a 2014 article for The Guardian. In the article, titled "Black People Were Denied Vanilla Ice Cream in the Jim Crow South – except on Independence Day," he wrote about how this practice was "custom" rather than "law." He also argued for its truthfulness because of the way it communicated to Black children about the rules of living in that time period. He wrote:

My father, for instance, first learned the rules when he first visited South Carolina with my grandfather in the 1940s. In our family's home county of Lancaster, Daddy asked the general store owner if he could buy some candy and ice cream, referring to the white man as "Sir". The store owner promptly grabbed my father by the collar, and yelled at him in the presence of my grandfather. Then he informed the elder man, "You'd better teach this little [N-word] to say 'Yassuh', boy! 'Sir' ain't good enough!" My grandfather grabbed his son and sped off.

At the end of the article, however, he wrote, "Perhaps the memory of being denied vanilla ice cream is not a literal memory for most: maybe it is just commentary. [...] The racism of the time period was not just about dignity and self-esteem – it was embodied and mythologized in physical terms."

We searched for first-hand historical accounts that corroborated the above custom of denying Black people vanilla ice cream (and permitting it on July 4). We reached out to numerous historians of Jim Crow and food culture, and will update this story as we learn more.

We also found a photograph on Getty Images of writer James Baldwin standing outside an ice cream parlor in 1963 in Durham, North Carolina. The door behind him said, "Colored entrance only," and a white man can be seen looking out the parlor window. It seems that the parlor was accepting Black customers while enforcing segregation, but whether they actually served them ice cream (or vanilla flavor) is up for debate and would require firsthand accounts from Black people in that parlor.

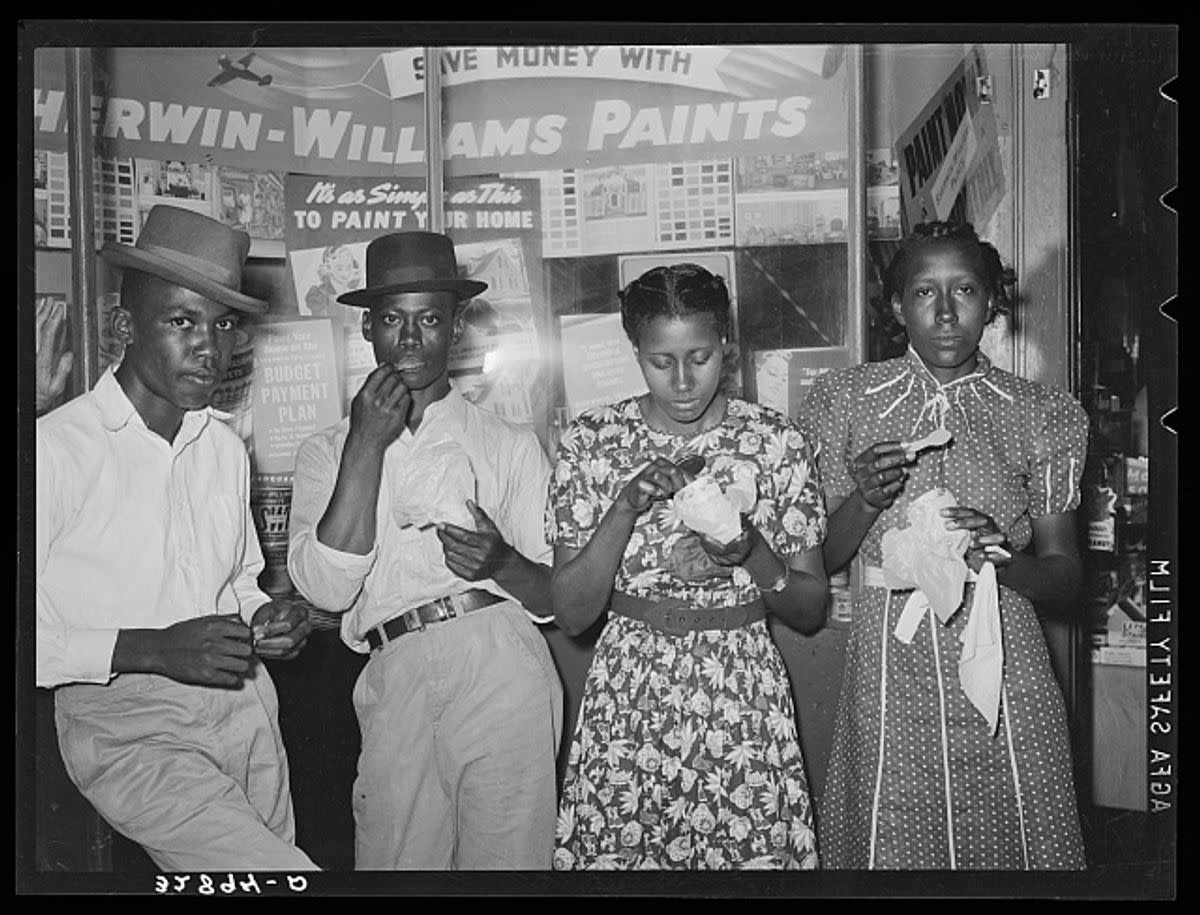

A 1939 Library of Congress photograph also shows a group of Black people eating ice cream in a public space, though the exact flavors are unknown.

(Russell Lee/Library of Congress)

Given that we could find no direct accounts that proved a connection between stories of discrimination from the Jim Crow era and the practice of denying vanilla ice cream except on July 4, it is likely they may fit into a wider pattern of white establishments generally denying services to Black patrons. In other words, the stories may have had little to do with the exact ice cream flavor, or the decision to only serve vanilla ice cream on July 4.

What Really Happened?

Did the above instances of discrimination never take place? Twitty's father's memory, along with Lorde's firsthand account of being denied ice cream of any flavor, certainly may have occurred (along with numerous stories of Black people being denied other services at establishments).

Were they connected to an unspoken rule of specifically denying vanilla ice cream except on July 4 to Black people? Even Twitty admitted to us that this may not have been the case, but it doesn't make the experiences of racism in general any less impactful.

When we asked Twitty for details around his vanilla ice cream claim, he expressed regret that his article had been taken literally. "I have some regrets about the story," he said, "But I forgive myself because I ask better questions now."

"With my father, I didn't hear the July 4 part [of the social media claim], but did hear about him being denied vanilla ice cream in South Carolina," he said.

He added that such histories are "colloquial and discretionary." He said, "Jim Crow wasn't logical, Jim Crow wasn't nice. It was about lynching children and putting men in their place. [...] Custom was worse than written law, and Jim Crow was about customs, where a Black man could not look a white woman in the eye [for example]."

He also brought up Angelou's reference to the lore in Arkansas. "That's where we get ideas of this apocryphal folklore that comes from real trauma in people's lives. This passes from person to person and turns into a commentary on American jingoism [referencing July 4]."

He also thought elements of the claim about Black people turning to butter pecan as an alternative as somewhat illogical. "When I wrote my commentary [in The Guardian], other readers connected it to butter pecan, while forgetting that [Black families] could make vanilla ice cream at home. It was the favorite ice cream in my household. Both my grandmothers had ice cream makers, there was no reason why they couldn't have made their own vanilla ice cream."

Darryl Goodner, co-owner of Louisville Cream in Kentucky and creator of the Butter Pecan Podcast, found that the vanilla ice cream story proliferated as folklore but remained unverified. "We don't have a definitive answer from the research, but it seems to be Black people chose whatever was the other things around," Goodner told the Louisville Courier Journal. "Looking at the South particularly, the flavor butter pecan makes sense. So many pecans are grown in Georgia." We reached out to Goodner to learn more.

Jennifer Wallach, professor of history at the University of North Texas, told us internet stories of Black people being denied vanilla ice cream were drawn from oral histories in Black families, but she had never run across any evidence showing this to be a widespread practice.

"I certainly would not want to refute those family histories, and I would guess that this kind of thing may have happened before. In this case, the core truth about inequality and discrimination, even over very trivial matters, is, of course, unambiguously true," she said.

However, she added, it was not a widespread practice simply because of economics:

I don't think the practice of denying vanilla ice cream was widespread for the fundamental reason that white business owners typically seemed content, or perhaps to put it more plainly, eager, to take Black money. In the drugstores, for instance, where many of the sit-ins took place in the 1960s, Black people could shop. They could spend money. They just couldn't sit at the lunch counter on equal terms with white customers. Restaurants, of course, often had separate seating areas or take-out windows for Black customers. These practices were designed to be humiliating and discriminatory but not to deny Black customers an opportunity to spend their money on goods. (There were exceptions, of course, like, famously, the Pickrick in Atlanta that would not serve Black customers at all.)

In general, Black and white southerners ate similar foods, and white supremacists relied on spatial cues to signal racial difference and Black inferiority, rather than refusing to eat the same foods or policing what could be eaten. There is, of course, an argument to be made about "white foods" as symbols of purity, etc. that could map onto white supremacy, but why would vanilla ice cream be singled out? Were Black people supposedly denied other white foods like historically coveted white bread or milk?

Many Black southerners were impoverished due to white supremacy, Wallach added, and did not have expendable income for luxuries like ice cream. "Focusing on the vanilla ice cream story could be a distraction from fundamentally more brutal truths about the impact of white supremacy on Black southerners," she continued.

But the story still proliferated because it struck a chord among Black people on social media.

"It's about sugar, dessert and pleasure. [...] It's about the denial of pleasure unless you have a certain skin color and privilege. [This discrimination] sounds diabolical because you are also denying a child. It does a good job of articulating what we can't otherwise say," Twitty said.

We have encountered such folklore emerging from historic moments of trauma before. In 2022, we reported on the internet claim that Black slaves would create maps in cornrows to help others escape slavery in the South. We could not definitively address the veracity of the claim but found that such stories mattered to the Black community as rich and varied tales surrounding their movement towards emancipation.

Over the course of our reporting on that story, Patricia Turner, folklorist and professor of African American studies at University of California Los Angeles, told us, "I am reticent to say anything too concrete, because I want lay people to want to know more about what life was like for enslaved people. There is no real value added to harshly saying "no" to a story."

She continued, "You can couch your language [and say] 'Well, no slave narrative covers it.' Others will say, 'Well that doesn't mean it didn't happen.'"

The same tension between history and folklore applies to this story as well. Whether Black people were denied a specific ice cream flavor over its symbolism is besides the point — the fact that they were denied similar services consistently and systematically is the underlying message of such lore that has persisted for generations.

Sources:

Angelou, Maya. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. New York : Bantam Books, 1971. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/iknowwhycagedbir0000ange_m6v8. Accessed 11 June 2024.

Cohen, Sascha. "Why the Woolworth's Sit-In Worked." TIME, 2 Feb. 2015, https://time.com/3691383/woolworths-sit-in-history/. Accessed 11 June 2024.

"Forced To Seat Blacks, Ala. Restaurant Complied With History." NPR, 13 Dec. 2014. NPR, https://www.npr.org/2014/12/13/370470745/forced-to-seat-blacks-ala-restaurant-complied-with-history. Accessed 11 June 2024.

Ghabour, Dahlia. "'Is Butter Pecan Ice Cream a "Black Thing"?' Louisville Podcast Explores How Race Impacts Food." The Courier-Journal, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/life/food/2021/01/26/black-owned-louisville-cream-launches-butter-pecan-podcast/4151700001/. Accessed 11 June 2024.

"How a 12-Year-Old Boy Made Vanilla a Global Spice." BBC, https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20240118-the-little-known-truth-about-vanilla. Accessed 11 June 2024.

Lee, Russell, photographer. "Negroes eating ice cream in front of hardware store. San Augustine, Texas." Apr. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, . Accessed 11 June 2024.

Lim, Angela. "'A Story of Survival': Food Influencer Explains the Racist History behind Butter Pecan Ice Cream." The Daily Dot, 27 June 2023, https://www.dailydot.com/irl/butter-pecan-ice-cream/. Accessed 11 June 2024.

Lorde, Audre. "The fourth of july." Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/the_fourth_of_july. Accessed 11 June 2024.

"Mississippi and Vanilla Ice Cream; a Complicated History." WJTV, 28 Feb. 2024, https://www.wjtv.com/hidden-history/black-history-month/mississippi-and-vanilla-ice-cream-a-complicated-history/. Accessed 11 June 2024.

Twitty, Michael W. "Black People Were Denied Vanilla Ice Cream in the Jim Crow South – except on Independence Day." The Guardian, 4 July 2014. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jul/04/black-people-vanilla-ice-cream-jim-crow-independence-day. Accessed 11 June 2024.

Twitty, Michael W. Phone call, 10 June 2024.

Wallach, Jennifer. Email, 11 June 2024.

"Writer James Baldwin Stands Outside an Ice Cream Parlor with a..." Getty Images, 26 Apr. 2016, https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/writer-james-baldwin-stands-outside-an-ice-cream-parlor-news-photo/525578174. Accessed 11 June 2024.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News