UK ‘strongly’ calls on China to reconsider Hong Kong’s new national security law

David Cameron has “strongly” called on Hong Kong to “reconsider” their proposal for a new national security law, which he said will inhibit freedom of speech, expression, and the press.

The British foreign secretary said Hong Kong’s new security legislation breaches its obligations signed under the British government’s handover deal of the former UK colony.

Hong Kong’s chief executive John Lee proposed the legislation on 20 January which is aimed at addressing what city officials call deficiencies or loopholes in the national security regime, which was bolstered just four years ago by another national security law imposed directly by China.

The one-month consultation period to pass the law ended on Wednesday and the Hong Kong legislature, which is dominated by pro-Beijing lawmakers, is expected to approve it.

The law, known as Article 23, will target crimes including treason, sedition, theft of state secrets, espionage, and "external interference" including from foreign governments.

Authorities have proposed harsher penalties for “seditious intention” and “possession of seditious publication”, an addition some lawyers say is concerning, as many journalists, activists and media outlets in recent years have been charged with sedition before being jailed or shut down.

Mr Cameron raised concern over the various features of the law, saying there is a “lack of clarity” and risks the work of international organisations in Hong Kong being labelled as “foreign interference”.

“My officials have raised our concerns privately with the Hong Kong authorities and through the public consultation process,” Mr Cameron said.

“I strongly urge the Hong Kong SAR (special administrative region) government to reconsider their proposals and engage in genuine and meaningful consultation with the people of Hong Kong,” he added.

The Chinese embassy in London on Thursday furiously pushed back against what it said was “groundless attack”.

It added that Hong Kong’s domestic legislation was “fully in line with international law and common practice in various countries and regions” and the declaration that Mr Cameron referred to did not give Britain the right to intervene in Hong Kong’s affairs.

In a separate and longer statement, China’s Foreign Ministry office in Hong Kong called the British government statement “irresponsible remarks” and “malicious smear”.

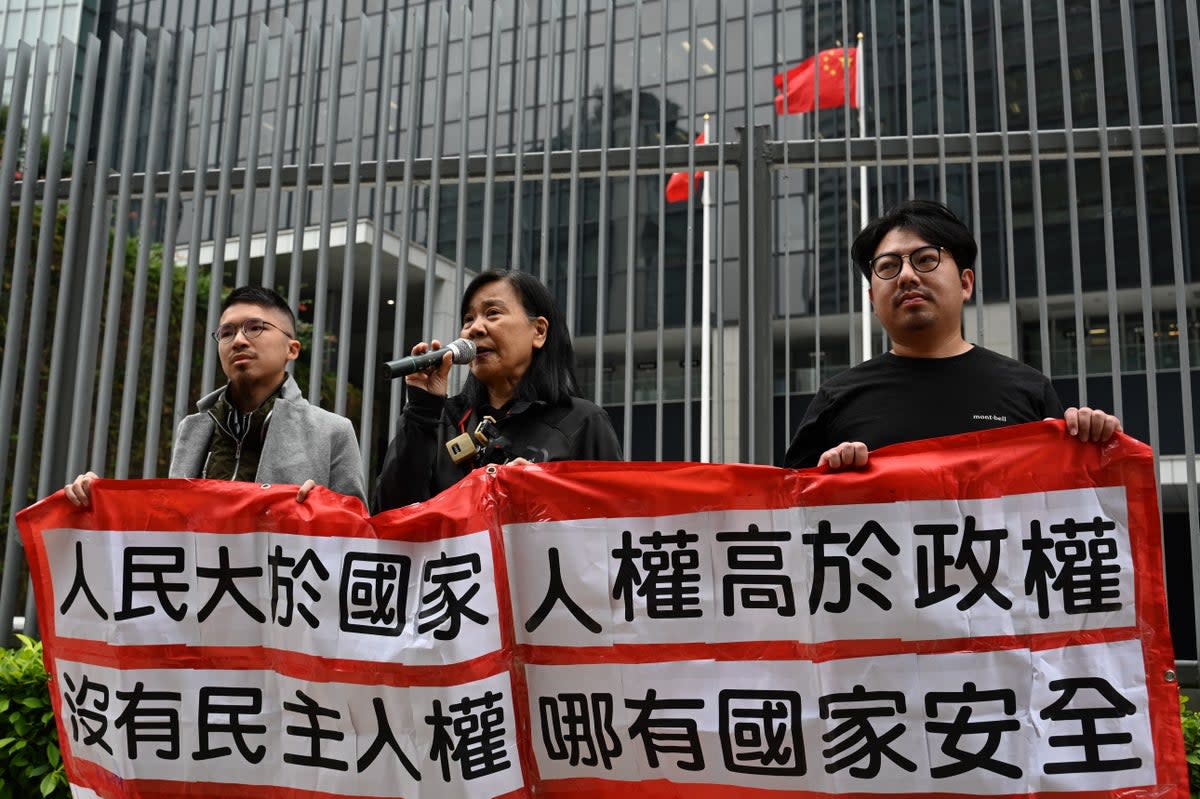

Activists and lawmakers have said the new law criminalises basic human rights such as freedom of expression.

"Many of these proposed provisions are vague and criminalize people’s peaceful exercises of human rights, including the rights to freedom of association, assembly, expression and the press," a group of 80 civil society groups, including British-based Hong Kong Watch, wrote in a joint letter.

"The United Nations Committee of human rights experts already concluded in 2022 that the sedition provisions should be repealed and Hong Kong should refrain from using them to suppress the expression of critical and dissenting opinions," said Mark Daly, a Hong Kong based human rights lawyer.

The Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA) said in its submission that "sedition should be abolished", adding the scope and definition of what constitutes "state secrets" was very broad and vague, especially in relation to newly added categories that include economic and social development.

In 2003, a prior endeavor to implement Article 23 was abandoned following approximately 500,000 people protesting against it. This time, there had been no significant protests, and the majority of public submissions received thus far endorse the legislation.

Additional reporting by agencies

Yahoo News

Yahoo News