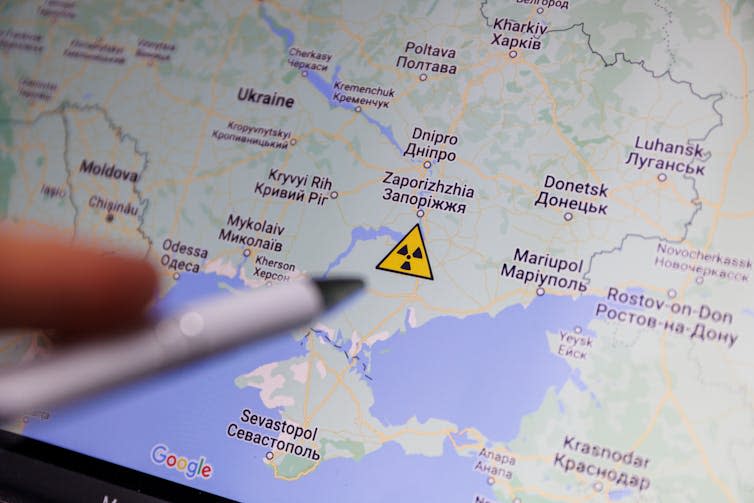

Ukraine war: Putin’s plan to fire up Zaporizhzhia power plant risks massive nuclear disaster

Recent reports of a series of drone strikes on Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP) have demonstrated the serious safety and security concerns at Europe’s largest nuclear power station. It has not been confirmed who is responsible for the strikes. Both Russia, which occupied ZNPP in March 2022, and Ukraine have pointed the finger at each other.

But Russia has recently announced plans to restart the plant. This would greatly increase the danger of a nuclear accident, as operating reactors allow much less time before an accident occurs if they are damaged or their safety systems are interrupted. The pressure and temperature inside an operating reactor are also much greater, creating the potential for large explosions and the widespread dispersal of radioactive material.

Read more: Ukraine war: the dangers following Russia's attack on the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant

The drone strikes started on April 7, in the first direct military action against ZNPP since November 2022. International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspectors deployed to monitor the site reported three drone impacts. Fortunately, none resulted in structural damage to critical nuclear safety or security systems.

The IAEA board of governors held an emergency meeting on April 17, passing a motion to call for the immediate return of control of the plant to Ukraine and the urgent withdrawal of unauthorised military and other Russian personnel.

Drones strike targets

Attacks have included a drone strike on the oxygen and nitrogen production facility, two on the training centre and a drone shot down above a turbine hall. The training centre, which was first attacked by Russian forces in March 2022, is a useful target for anyone seeking to emphasise the threat posed by the plant without actually sparking a disaster. It is clearly part of the power plant, yet is isolated and likely contains little to no nuclear material, meaning the risk of resulting nuclear accident is relatively low.

Who launched the attacks has yet to be determined – and their intention remains unclear. The IAEA has repeatedly stated that there can be no benefit to any party from a nuclear disaster at the plant. But the unstable security situation at the plant may hold value for Russia as it could be used to pressure Ukraine and its international allies to accept an resolution to the conflict that favours Moscow. Ukrainian personnel still working at ZNPP have claimed that Russia has turned the plant into a military base.

During the second half of 2022, after ZNPP was captured by the Russians, the plant was subject to regular shelling, for which – as has happened recently – Russia and Ukraine blamed each other. Since Russia gained control of ZNPP, Ukrainian staff have remained at their posts to prevent accidents, despite indications of mistreatment, kidnap and even torture by Russian occupiers.

Like any modern nuclear power plant, ZNPP possesses a wide range of safety and security features, allowing it to weather occasional relatively minor attacks – such as the ones launched so far in this conflict. But it is far from invulnerable. A major attack would have the potential to cause a serious nuclear accident.

The IAEA continues to call for restraint and for all military activity to be halted in the vicinity of the plant.

A risky restart

The Russian president Vladimir Putin has reported to the IAEA that he wishes to see ZNPP restarted. But the skeleton crew of Ukrainian experts who have remained at the site, and have been coerced into accepting Russian passports and signing Russian contracts, would not be sufficient to do this safely. Meanwhile any Russian nuclear experts charged with restarting the plant would be challenged to understand the specifics of ZNPP, given the many changes made to it since its construction.

Ukrainian staff recently placed the final ZNPP reactor into a state of “cold shutdown”. This means the cooling water in the reactor is below 100°C and at atmospheric pressure. This is safer than the previous state of “hot shutdown”, but a restart would be far worse than either of these. If the reactor or associated equipment and its containment were to be breached, cooling water and potentially nuclear material could be ejected with great force into the atmosphere and spread over huge distances.

ZNPP has struggled through the past two years with unreliable access to cooling water, back-up electricity, staff numbers and more. Putting ZNPP, a plant still on the front line of an armed conflict, into operation would therefore be highly risky.

Critical safety systems and resources at the plant are severely strained. The plant relies on access to large volumes of cooling water to remove heat from its nuclear fuel, even in shutdown conditions. The destruction of the Kakhovka dam last year greatly reduced the ability of ZNPP operators to draw cooling water from the Dnipro River.

Is there any benefit that makes this risk worthwhile? It does not appear so, primarily because there is very little demand for the energy the plant could produce. The nearby population has largely evacuated, and Ukraine currently refuses to accept power from Russia. That said, Russia has recently redoubled its efforts to target Ukraine’s energy infrastructure and may be trying to engineer a situation where Ukraine has to accept energy supplied from power plants in regions of the country occupied by Russian forces.

Another possibility is that Putin, who has an eye for the historical gesture, wants to reactivate the plant in time for the 40th anniversary of its connection to the Soviet power grid in December 1984. In either case, the risks seem hard to justify.

Another noteworthy anniversary is on April 26. Chernobyl Remembrance Day commemorates the world’s worst nuclear disaster, which occurred in 1986 in what is today Ukraine. Thirty-eight years later, Moscow officials are risking creating another major nuclear disaster for the Ukrainian people.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ross Peel is affiliated with the Centre for Science & Security Studies at King's College London.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News