Voices: You don’t need to worry about the New York Times making Elizabeth Holmes look good

Elizabeth Holmes got a profile in The New York Times and a lot of people are mad about it. Holmes — now known by friends and family as “Liz” — is awaiting transfer to prison to serve 11 years, and in the meantime, she’s been going to the zoo with her boyfriend (Billy Evans) and two children (William and Invicta), renting vacation homes near the sea, volunteering for a rape crisis line, and spending time with her dog. In an intimate feature, one Times journalist describes how she spent days with the young family, joining trips, sharing breakfasts and joking about that weirdly low voice Holmes used to put on back when she was a Silicon Valley grifter in her early twenties. The reporter marvels at just how normal Holmes seems, sitting on her sofa with her baby at her breast or wiping dog slobber off her companion’s shoe. Despite the fact that she and her husband clearly live on the wealthy side of normal — not everyone loads their two kids into a Tesla every morning — it’s pretty clear that neither of them are villains and Elizabeth Holmes is not, in fact, the embodiment of evil. This has led to a lot of disgruntled commentators claiming that the Times is “laundering” Holmes’ reputation.

At first, it seems like a fair criticism, considering that the author, Amy Chozick, admits to getting carried away with the quietly charismatic Holmes. In a meta moment, she even describes how her own editor told her she’d been “rolled”, and how defensive she got about it (“You don’t know her like I do”.) Holmes clearly feeds her a lot of BS that sidesteps the damage she did by setting up a fake biotech firm that delivered erroneous blood tests results on the regular. “I made so many mistakes and there was so much I didn’t know and understand, and I feel like when you do it wrong, it’s like you really internalize it in a deep way,” she says at one point. To which most normal people might respond: Yeah, but what about the woman who got falsely diagnosed with HIV by a Theranos test? Or the guy who stopped taking his blood thinners after being told his blood wasn’t clotting like normal?

But that’s why Chozick’s detailing of how she was almost fully taken in by Holmes is an important read. It’s a big person who is able to admit that they were fooled, and it’s clear that in some of the time the reporter spent with Holmes and her family, she was. Holmes is not a flashy, stereotypical scammer. She’s quieter, more considered, yet she’s very convincing. Rupert Murdoch parted with hundreds of millions of dollars after meeting her. So did an eye-watering number of other established, experienced investors. The Elizabeth Holmes story is fascinating precisely because we all want to know how on earth that happened in the first place.

Chozick gives us a microcosmic view of that dynamic. She charts exactly how easy it is to be taken in. “Ms. Holmes’s story of how she got here — to the bright, cozy house and the supportive partner and the two babies — feels a lot like the story of someone who had finally broken out of a cult and been deprogrammed. After her relationship with Mr. Balwani ended and Theranos dissolved, Ms. Holmes said, ‘I began my life again,’” writes Chozick. “But then I remember that Ms. Holmes was running the cult.” Clearly, Holmes can spin a believable narrative and deliver it in an authentic-seeming way. Surprise, surprise — one of this decade’s most famous con artists is good at conning.

Holmes still thinks she has something to give the world of biotech innovation, apparently. She tells Chozick she’d love to get back into that space — after her 11 years in prison. Such asides give the impression that she’s so good at scamming because she’s fueled by self-delusion. When she talks about what happened at Theranos, she lumps all the blame on her partner, Sunny Balwani (also in prison for 11 years for his part in the fraudulent operation of the company.) She was the CEO, so that’s not very convincing. Equally, there are shades of grey in her story. She was 19 when she founded Theranos. Balwani was her romantic partner as well as her business partner, he’d already founded and sold a successful startup, and he was almost 40 years old.

That context matters, even if it doesn’t excuse her for what she did. In the same way, it matters that she’s famous, wealthy and white, and she’s getting to spend her last few days before her sentence with her children at the zoo rather than locked up in a jail cell like so many of her poorer, less privileged counterparts. The fact that Silicon Valley routinely rewards behavior like hers and Balwani’s — “faking it til you make it” with a startup, even when that startup involves risky forays into the medical sphere — also matters. In Chozick’s article, she asks Holmes what she thinks would have happened if the media hadn’t caught up with her so fast (Holmes was hailed as a wunderkind of the industry in the early days of Theranos, pasted on front pages, interviewed relentlessly, and then eventually investigated and shown to be a fraud by The Wall Street Journal.) Holmes responds that she thinks they would have achieved their aims and changed the medical landscape forever.

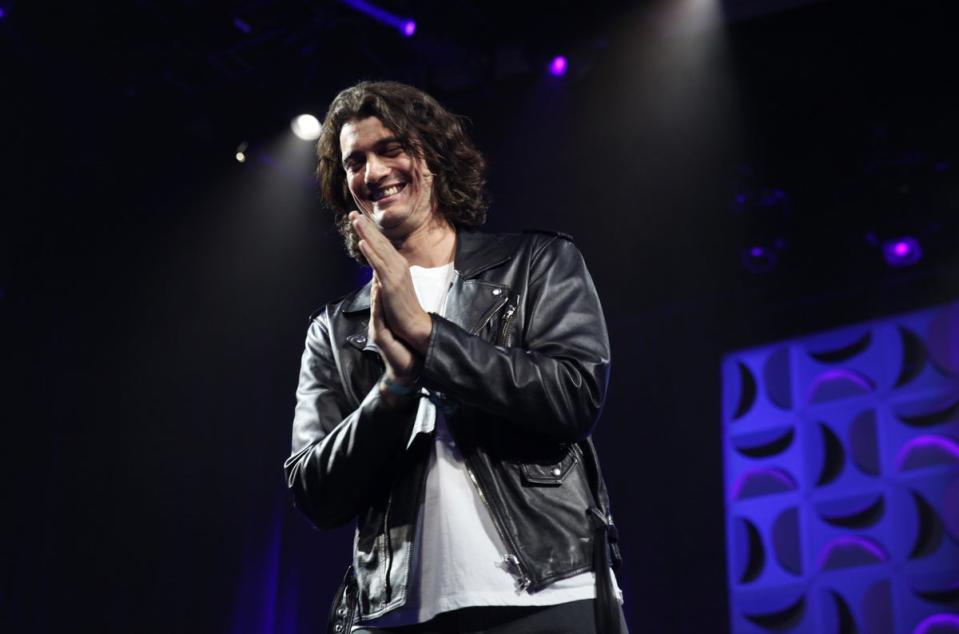

Chozick dismisses this kind of thinking as fantastical, but it isn’t in the context of how so many west coast VC firms and startups work. Many have begun with an idea that isn’t fully developed, or isn’t profitable, or isn’t workable, and endeavored to simply “make it up as we go along”. Uber has never made a profit. Netflix decided at its inception that it would do something with the internet and movies, but hadn’t really worked out what yet (and it didn’t work out that connection until it pivoted to streaming, years after spending time sending out DVDs to customers.) People poured money into Fyre Festival. WeWork was the darling of the industry for years, sucking up investor funding and convincing everyone it was a tech startup with a promising future — until everyone realized it was actually just a business that bought up real estate and used its investment funds to rent out offices for cheap. There was no way it was ever going to make a profit after the financial backing ran out.

WeWork’s former CEO, Adam Neumann, was widely mocked in the media after his business collapsed. Like Holmes, he had a miniseries made about him — WeCrashed, made by Apple TV — in which he was portrayed as another modern grifter who destroyed the lives of the people he promised to elevate. He was parodied on unrelated shows. There was even a movie: WeWork, or The Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn, on Hulu.

But where is Neumann now? Back in the game, with a new startup called Flow that wants to build high-quality housing promising “a sense of community” for young professionals. It sounds like the residential version of WeWork. It sounds like, once again, it’s just a business, not a tech startup. It sounds unsustainable. That doesn’t matter to the big players of Silicon Valley, who just cut him a check for millions of dollars.

Neumann didn’t commit any crimes, of course. But he proved himself an inadequate businessman who made bad calls. He lost a lot of people their jobs and their money. His career took a minor hit and is now resurrected in almost identical form. So is Holmes saying that she wants to re-enter the biotech space really that unrealistic? Is she really so out of touch?

One slightly sympathetic profile isn’t going to change Holmes’ sentence, or change many people’s minds about what Theranos was all about. But even if it did and Holmes walked free tomorrow, the Silicon Valley mindset would still be a problem. So long as people like her — charismatic, slightly deluded, ambitious beyond their abilities, willing to put on a black turtleneck and play to a crowd of moneyed men who also don’t have that much of a clue themselves — are handed millions of dollars for saying the right combination of west coast buzzwords, then the risk will still seem worth it to the grifters of the future.

Don’t worry about whether Elizabeth Holmes is a dog person now, according to one journalist who was honest to a fault. Worry about who comes after her.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News