The Voyager spacecraft will probably last a billion years, says a scientist on the mission for nearly 5 decades

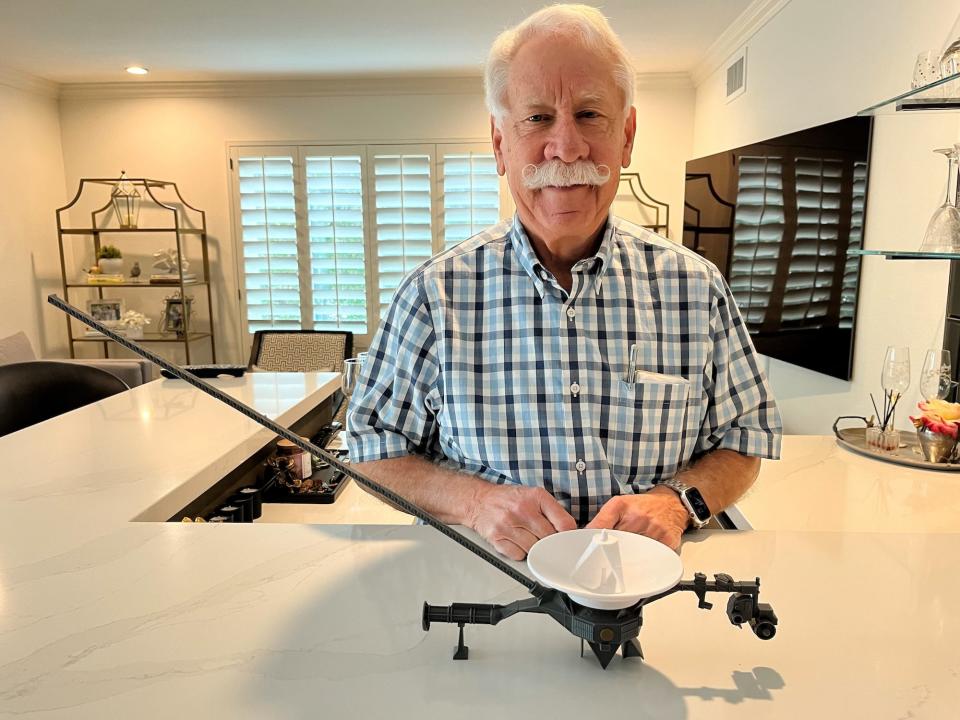

Alan Cummings has worked on the Voyager mission for over 50 years.

Since their launch, the two Voyager spacecraft have made breakthrough discoveries that keep Cummings engaged.

Cummings thinks they will continue traveling for a billion years.

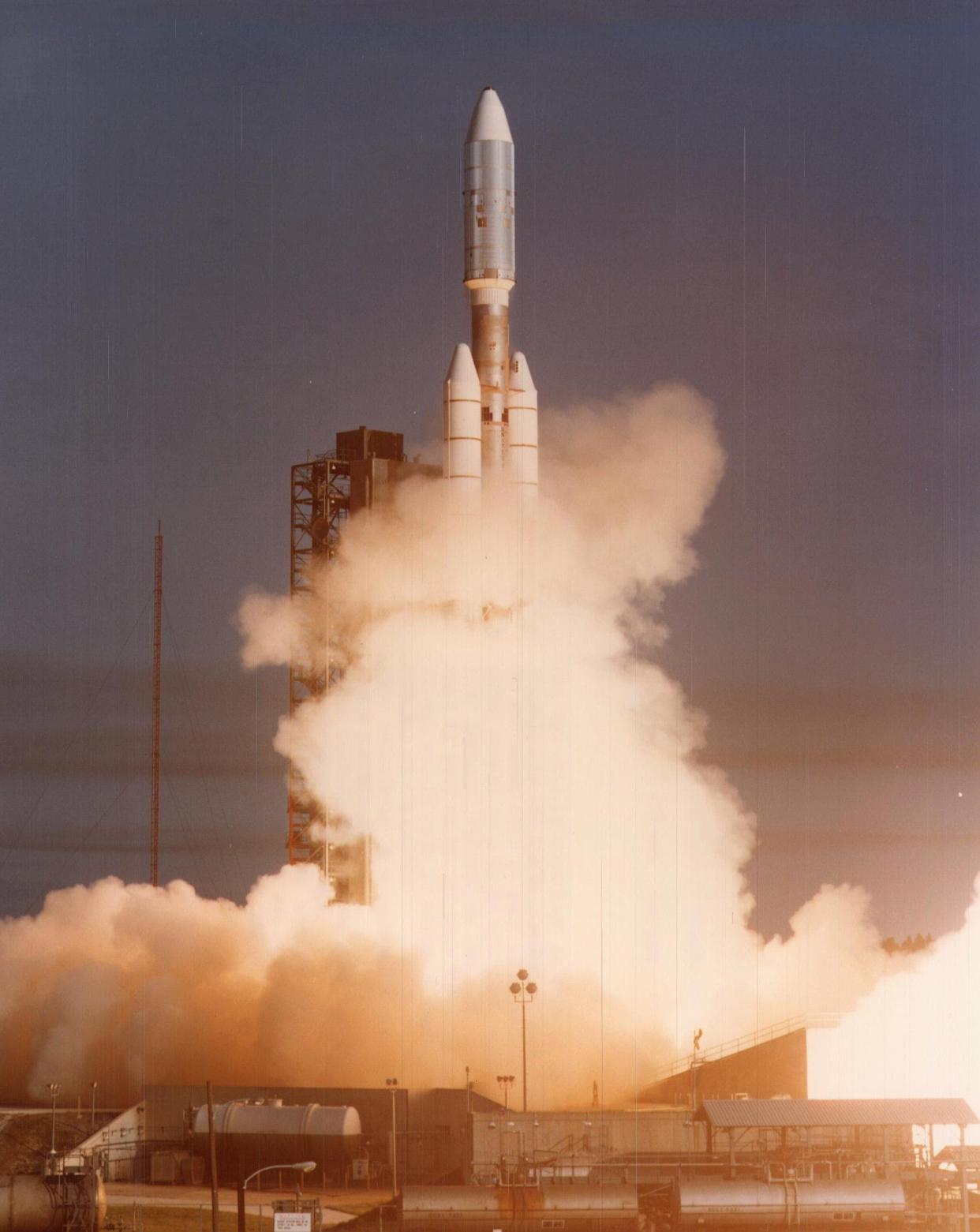

The twin Voyager spacecraft launched almost five decades ago, and there's no reason they shouldn't keep going for a billion years, one of its scientists, Alan Cummings told Business Insider.

Cummings started working on the Voyager mission when he was a graduate student at Caltech in 1973, about four years before the two spacecraft launched.

Now a senior research scientist at Caltech, Cummings has seen the program dwindle from over 300 people to fewer than a dozen.

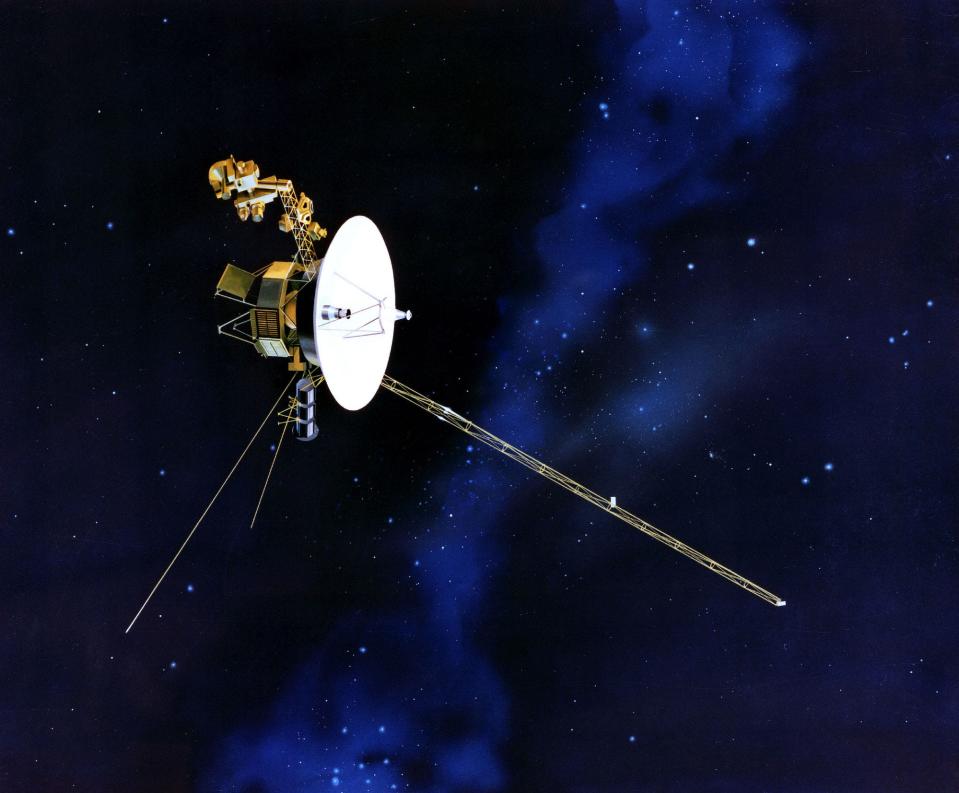

Voyagers 1 and 2 have traveled over 10 billion miles into space, further than any human-made object. Cummings said being a part of this historic mission for so many decades has been the backbone of his career.

"The Hubble Telescope is a great mission," he said. "JWST is a great mission, but I think Voyager's in that kind of category."

Voyagers' endurance

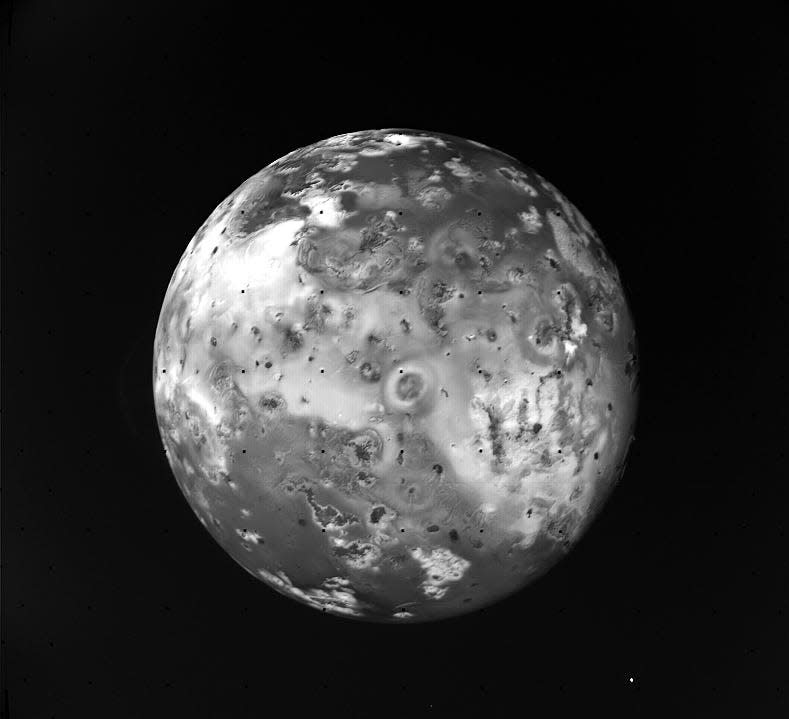

The Voyager mission has been gathering groundbreaking data and photos since the beginning.

The first time Cummings saw Jupiter's moon Io in 1979, for example, he thought it was a joke. "It looked like a poorly made pizza," he said.

Its colorful, volcano-covered surface looked so different from Earth's gray, pockmarked moon. "This can't be real," he said, "and it was real."

The Voyagers offered us a new perspective on our outer solar system, unlike anything we could have imagined.

They discovered Saturn wasn't the only planet with rings — Jupiter has them too. They revealed new moons around Jupiter and Saturn.

In total, the two spacecraft snapped 67,000 images of our solar system, the final of which was the "pale blue dot" photo made famous by Carl Sagan who said:

"To my mind, there is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world."

"It rewrote the textbooks," Cummings said of the mission.

Both Voyagers were initially planned as five-year missions, but Cummings said, from the beginning, he expected the spacecraft to last at least 30 to 40 years.

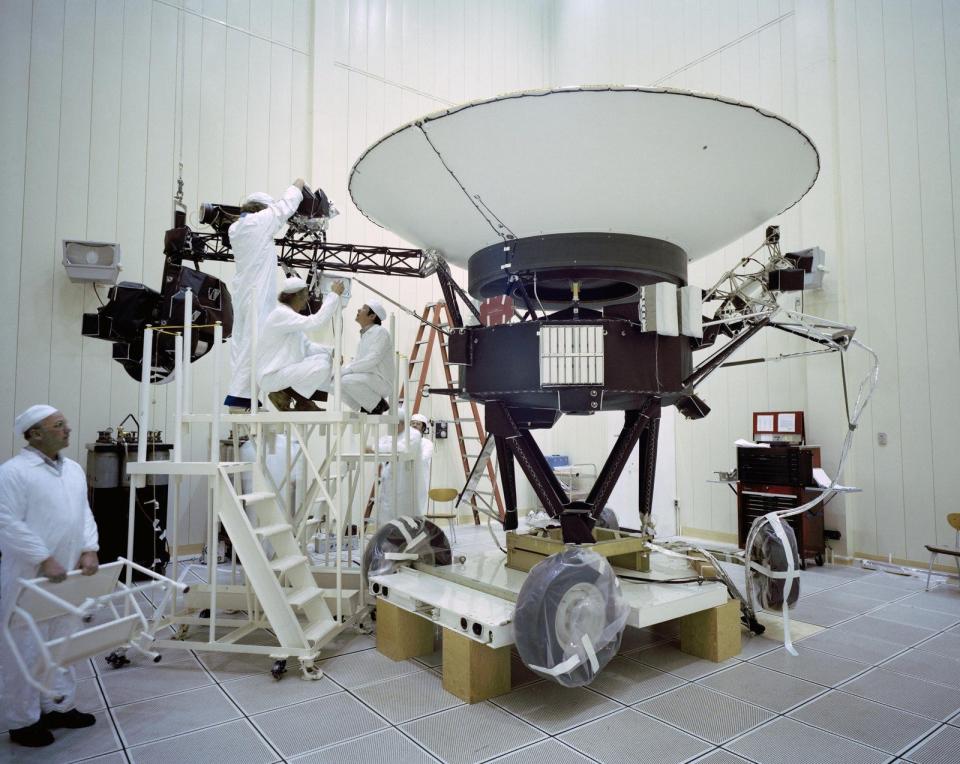

"A remarkable engineering team has kept this thing going," Cummings said.

Now, as the two spacecraft approach their 50th anniversaries, they're running low on fuel.

Engineers have had to shut down different instruments to keep them going and the data coming in.

Cummings said once the Voyagers lose power and communication, they'll continue traveling. "I think it's going to go for a billion years," he said. "There's nothing to stop it."

Joining Voyager

If it weren't for an unfortunate accident, Cummings may never have joined the Voyager mission.

Before Voyager, Cummings was part of an experiment to measure cosmic rays using a balloon.

For several summers, he had released the balloon from northern Manitoba, Canada.

But during its final flight, the balloon didn't descend as expected and ended up over Russia, instead.

By the time Cummings got to Russia, the instrument was destroyed.

"It was very fortunate for me," he said, because he was able to then join the Voyager mission.

He put his cosmic ray experience to use, working on telescopes for the mission's experiments.

"I have my little initials scratched on one of those" telescopes he said, "so I guess I'm going to be immortal."

Interstellar space

Cummings has worked on other projects over the decades, but Voyagers' continual transmission of new data has kept him excited and involved.

"There's always some new phenomenon that you see," he said.

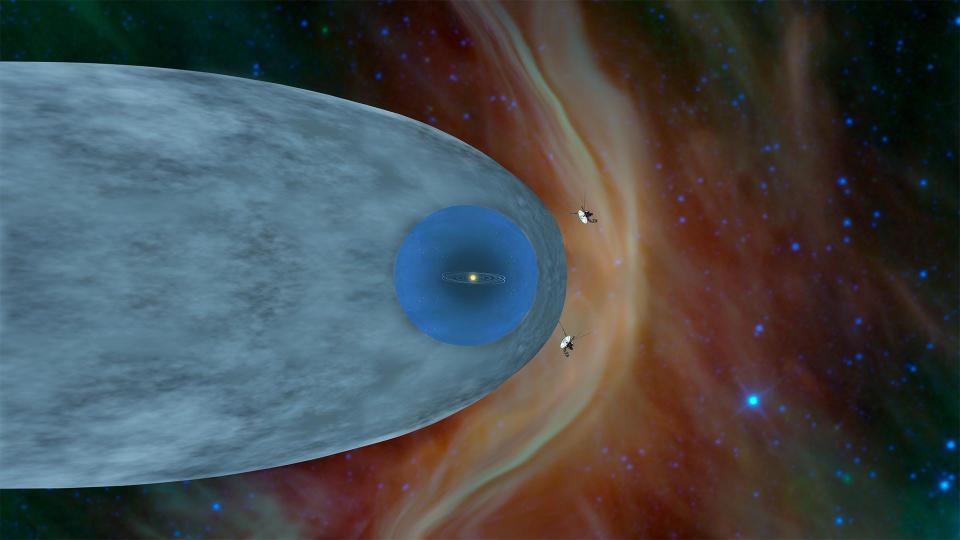

In fact, Voyager's data has become increasingly more interesting to Cummings in recent years because the two spacecraft are now in interstellar space, the region of space beyond our sun's influence.

After passing by the four giant planets of Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, and Uranus, many of the instruments were still in working order. So, the spacecraft transitioned to an interstellar mission.

In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made spacecraft to enter interstellar space and Voyager 2 followed six years later.

"That is really what I was most interested in anyway," Cummings said, since cosmic rays are his field of expertise and in interstellar space, those rays aren't disrupted by the sun, Earth, and other obstructions in our solar system.

Voyager is "making its most interesting measurements in some ways right now," he said.

Currently, Voyager 1 is having issues with one of its onboard computers that could compromise the mission.

Cummings hopes the Voyagers can hang on a little longer, especially since interstellar space is a long way off for any other spacecraft.

Read the original article on Business Insider

Yahoo News

Yahoo News