Where do all the parties stand on tax cuts and spending – and are their manifestos fully costed?

With the general election only days away, all the major parties have now released their 2024 manifestos which outline their policy agenda for the country.

Topping many people’s priority list is what any new government could mean for their income. The cost of living crisis has hit the UK hard over the past two years, and has resulted in much less spending power for most.

As such, the Conservatives and Labour have both avoided measures that raise personal taxes in their offerings. And while other parties have looked at raising taxes on businesses or investments, none are proposing rises to income tax or national insurance.

A key question for any manifesto document is whether the government will be able to afford what they are offering. The general rule is that at least as much money must be raised (from increased taxes, for instance), as is proposed to be spent.

There is some debate about this, however, with some parties far more comfortable to borrow and increase the national debt than others.

Here’s everything you need to know about where all the parties stand on tax cuts and spending – and how they’ve costed their manifestos:

Labour have ruled out tax raises, promising a there will be no increase to income tax, national insurance or VAT if they secure victory in July. The party has also pledged to cap corporation tax at 25 per cent – the level it was increased to in 2021.

On the economy, the party says it is guided by ‘securonomics’, a fiscal principle spearheaded by shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves. Their manifesto draws a direct contrast between this approach and Liz Truss’ disastrous 2021 ‘mini-budget’ which saw immediate and long-lasting economic repercussions.

The party says it would strengthen the role of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), which was a bugbear of Ms Truss’ during her time in power.

Labour’s manifesto says it is the ‘party of wealth creation’. Their approach is to improve the prosperity of the country with ‘sustained economic growth’, rather than many increased revenue raising measures.

However, the document commits to the lowest revenue raising and spending of all party manifestos, at just £4.74bn from £4.77bn. This figure is raised from measures such as closing non-dom tax loopholes, applying VAT to private schools, and £3.5bn of borrowing.

Paul Johnson, director of the respected Institute for Fiscal Studies called the manifesto’s public spending promises “tiny, going on trivial”.

“Delivering genuine change will almost certainly also require putting actual resources on the table,” he said. “And Labour’s manifesto offers no indication that there is a plan for where the money would come from to finance this.”

The Conservatives have similarly ruled out increasing taxes: income tax, VAT and corporation will stay the same should they secure another term. But, unlike Labour, they have pledged an additional 2p cut to national insurance, which would bring it down to 6 per cent (by 2027).

The party’s headline economic goals are to reduce borrowing and debt, and backing businesses to invest and trade in the UK. Their accompanying costing document says the party plans to raise £18bn and spend £17.7bn annually by 2029-30.

The IFS’s Mr Johnson says he has a “degree of sceptiscism” about the Conservatives’ costing strategy as “definite giveaways paid [are] for by uncertain, unspecific and apparently victimless savings.”

“This manifesto remains silent on the wider problems facing core public services”.

Meanwhile, the Lib Dems have said they will cut income tax by increasing the tax-free personal allowance, which was frozen at £12,570 by the Conservatives in 2022.

Sir Ed Davey’s party also plans to reform capital gains tax and make it ‘fairer’. They would do this by introducing three rates, similar to how income is taxed, raising the personal allowance from £3000 to £5000, and ensuring earnings made soley from inflation aren’t taxed.

The party also says it would reverse tax cuts for big banks and implement a one-off windfall tax on the ‘super-profits’ of oil and gas companies.

For the wider economy, the Lib Dems say they will protect the independence of the Bank of England and ensure inflation remains at its 2 per cent target. They also promise to ensure all fiscal events are accompanied by forecasts from the OBR.

Outside a few substantial pledges,” says Mr Johnson, “the Liberal Democrats are promising a long list of small additional things they want the state to do. Together they would likely make it harder to address the big challenges with funding our core public services.”

The Greens have pledged the most spending and revenue raising measures of all parties. The party says they would not raise the basic rate of income tax during the cost of living crisis, but introduce a wealth tax. This would see the wealth of individuals with assets over £10 million taxed at 1 per cent, and with assets over £1 billion at 2 per cent.

They would also reform capital gains tax to align its rates with income tax, and scrap the upper limit of national insurance tax. Overall, the party predicts all their propsosed tax raising measures would raise between £50 and £70bn a year.

Alongside changes to how property and business is taxed, the Greens say they would have the revenue to put £40bn a year into “green economic transformation.” They are also the only party backing full privatisation of public utilities.

Unlike the other parties, the Greens have been far more comfortable about borrowing to fund their policies. Their manifesto calls conventional fiscal rules a “self-imposed straitjacket,” with borrowing proposals that would reach record levels.

“Even taking their figures at face value, overall borrowing would end up around £80 billion a year higher and we could expect debt to be rising throughout the next Parliament,” says IFS deputy director Helen Miller.

“It is unlikely that the specific tax-raising measures they propose to help achieve all this would raise the sorts of sums they claim - and certainly not without real economic cost.”

On the opposite end of the spectrum is Reform UK. The party says it would immediately lift income tax allowance to £20,000, and the higher rate to £70,000. They want to lower fuel duty by 20p per litre, and scrap both VAT on energy bills and environmental levies.

This would come alongside even more tax-cutting measures such as reducing the Stamp Duty allowance to cover properties up to £750k – up from the current £250k – as well as bringing corporation tax down to 15 per cent by their third year.

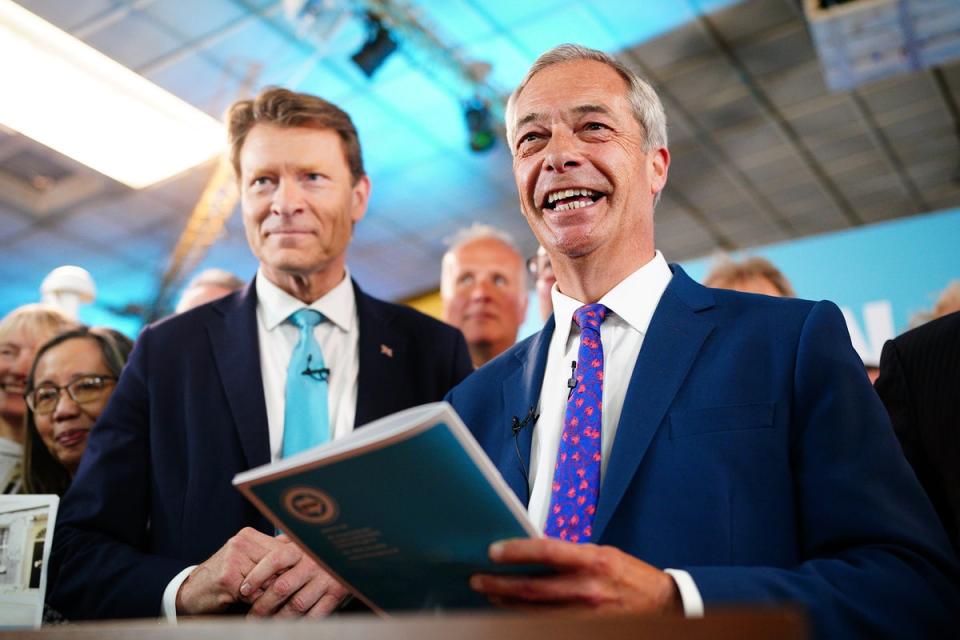

Nigel Farage’s party says it would fund this by scrapping funding which goes to managing migrants, scrapping net zero and slashing ‘wasteful government spending’.

The party’s own figures suggest they would raise £150bn annually (plus an extra £10bn after growth), funding £141bn worth of policies.

Carl Emmerson, deputy director of the IFS, has criticised Reform, saying “the sums in this manifesto do not add up”.

“In reality the package of tax cuts proposed would, if and when fully implemented, cost tens of billions of pounds a year more”

“The manifesto costing of £18 billion a year over the course of the next parliament for all its business tax cuts is less than half of what official estimates suggest the long-run cost of just this cut in the corporation tax rate to 15% would be.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News