Why is air pollution in London so bad? 10 years on from Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah’s death

Today (15th February) marks the ten-year anniversary of the death of Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, who was the first person in the UK to have air pollution listed as a cause of death.

In the early hours of February 15, 2013, nine-year-old Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah died following a severe asthma attack.

In the three years prior, Ella, who lived near the South Circular Road in Lewisham, had visited the hospital nearly 30 times and endured multiple seizures. In December 2020, she became the first person in the UK to have air pollution listed as a cause of death.

According to a recent study, teens in London who are exposed to air pollution over an extended period of time have higher blood pressure.

The research, led by scientists from King’s College London, showed a stronger association in girls, caused by tiny air-pollution particles. The researchers theorised this could be because the boys studied were more physically active and had greater lung capacity.

Researchers examined information from more than 3,000 teenagers.

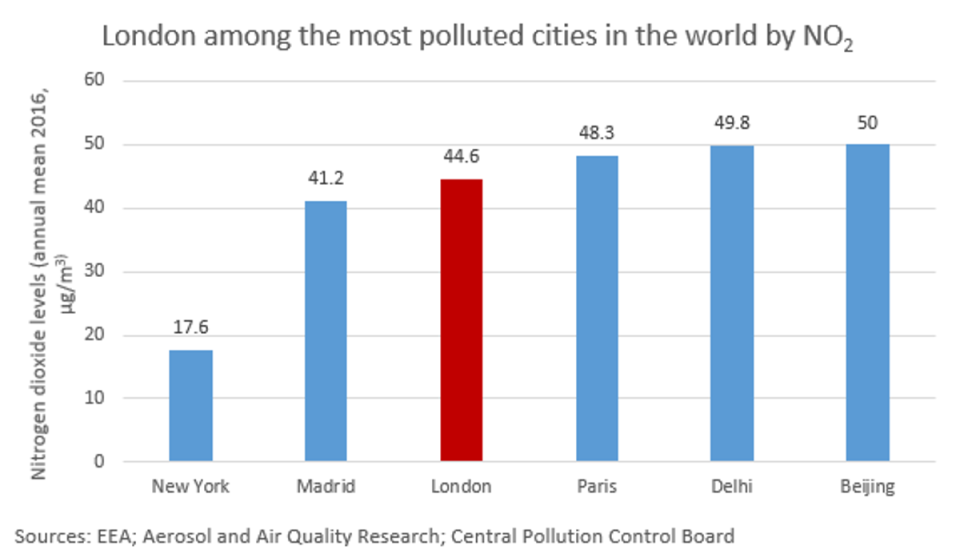

Additionally, they discovered that exposure to high concentrations of nitrogen dioxide (NO2), a pollutant from diesel vehicles, was linked to a reduction in blood pressure. Pollutants from diesel transportation include NO2.

London has reported illegal levels of air pollution since 2010 and it contributed to around 6,000 excess deaths in the capital in 2019, according to new research.

So why is air pollution such a problem in the capital, and what can be done about it?

Why is air pollution so bad in London?

The sheer size of London, combined with a dense road network and tall buildings, means central London is one of the most polluted places in the UK, according to the London Air Quality Network. Pollution builds up when it becomes trapped between buildings, especially during still weather.

Road vehicles are the leading cause of London’s air pollution, generating half of the nitrogen oxides and particulate matter that clog the air and seep into our lungs, according to TfL. They cause congestion — costing the capital billions of pounds a year — and, by emitting carbon dioxide, contribute to climate change.

Dr Audrey de Nazelle, co-deputy director of the Centre of Environmental Policy at Imperial College London, said: “Nitrogen dioxide is mostly in London due to transport emissions, which are exacerbated by congestion in the city.”

Traffic speeds in central London average eight miles per hour on weekdays, a figure that has decreased in recent years.

Although the total number of vehicles entering central London has fallen drastically since the congestion charge was introduced, the number of private-hire vehicles entering central London — which are exempt from the charge — has more than quadrupled over the same period.

How dangerous is air pollution?

In short, very. A study published in The Lancet Planetary Health in January 2022 suggested that air pollution in urban areas across the globe contributed to 1.8 million excess deaths in 2019, making it a bigger killer than tobacco smoking. Of those, 5,950 were in London, 1,330 in Birmingham, 730 in Leeds, and 670 in Liverpool.

Another study by the same researchers showed that in 2019, one in 12 cases of asthma among children worldwide were attributed to nitrogen-dioxide pollution at levels exceeding World Health Organisation guidelines. In the UK, London was again responsible for the most cases, at 10,770.

Dr de Nazelle explained to the Standard why air pollution poses such a threat to public health.

“Because of the way air pollution enters the body through our lungs and into the bloodstream, it can be carried to many different organs,” she said.

“That’s why it is linked to so many diseases, like diabetes, obesity, low birth weight, premature birth, and cognitive-development issues. It also makes us vulnerable to other diseases, as we’ve seen with Covid-19.”

Researchers cannot experiment on people and so, by necessity, many studies show significant associations between poor air quality and disease, but cannot prove cause and effect.

Particularly compelling evidence comes from China, where government action to slash pollution before the Beijing Olympics in 2008 led to a rise in birth weights in the city.

Does air pollution in London affect people equally?

In many cases, air pollution exacerbates pre-existing inequalities. Nearly half of London’s most-deprived neighbourhoods exceeded EU nitrogen-dioxide limits in 2017, compared with just two per cent of its wealthiest areas, according to data from the European Environment Agency.

Between 31 and 35 per cent of areas with the highest proportion of black and mixed ethnicities are in areas with higher levels of air pollution. Southwark, Lambeth, and Hackney are among the boroughs with an overlap of both a higher proportion of black residents and higher pollution levels.

On top of this, the people whose health is most affected by air pollution often contribute the least to the problem.

Kate Langford, director of the Health Effects of Air Pollution programme at Impact on Urban Health, told the Standard: “It’s cars from the wealthiest households that contribute the most to transport-related pollution.”

This has been the subject of recent protests over plans to expand a waste incinerator in Edmonton, north London. It sits in one of the poorest areas in the country, where 65 per cent of residents are from ethnic-minority backgrounds, and air pollution already breaches legal limits.

“It’s a poster child for environmental racism,” said Carina Millstone, the initiator of the Stop the Edmonton Incinerator coalition. “We know that poorer communities and communities of colour bear the brunt of the climate crisis. This proposal to pollute the air of Edmonton for another 50 years is inherently unfair and racist.”

Delia Mattis, founder of Black Lives Matter Enfield, pointed out the contradiction between the decision to expand the Edmonton facility and the Government’s rejection of an incinerator in a leafy part of Cambridgeshire in 2020.

“Incinerators are three times more likely to be built in areas of deprivation”, she told the Standard. “Edmonton is already over-polluted by traffic from the North Circular. If it’s not good enough for Cambridgeshire, then it’s not good enough for Edmonton.”

What does it mean when an air pollution warning is issued?

Vulnerable Londoners were warned to reduce strenuous physical activity due to high air pollution levels on January 14.

When air-pollution ratings are “high”, which means a rating of seven to nine, members of the public are told to consider reducing outdoor activity if they find themselves “experiencing discomfort, such as sore eyes, cough, or sore throat”.

Stronger advice is issued for at-risk parts of the population, which includes adults and children with lung problems, and adults with heart problems.

London saw an overall high ranking for air pollution just once last year, when UK air ranked levels at eight out of 10 on March 31. Air pollution is “particularly high” between three to eight times a year, according to city hall.

So, what can be done to tackle air pollution in the capital?

Sadiq Khan, himself an asthma sufferer, has made fighting air pollution a key priority.

His latest considerations, a possible daily levy of £2 to drive a petrol or diesel car in London, go even further. The Mayor is also considering expanding the ultra-low emission zone across all of Greater London’s 33 boroughs, well beyond the Ulez’s current boundary of the North and South Circular roads.

Dr de Nazelle said: “Tackling air pollution by reducing car journeys is key. It is also an opportunity to bring about health improvements in other ways. Reducing the number of cars on the street removes traffic injuries, creates space for safe walking and cycling, and green space and trees have health benefits.”

Research suggests that more than a third of car trips made by Londoners could be walked in under 25 minutes and two-thirds could be cycled in under 20 minutes. But recent TfL figures have shown the number of road journeys have returned to levels almost as high as were seen pre-pandemic.

“It’s unacceptable that it’s easier for Londoners to have a parking space than it is space in a bike hanger,” said Kate Langford, from Impact on Urban Health.

“We must also improve public transport, and make sure it’s as affordable and efficient as possible. If buses can travel just 1mph faster than they do today, it could potentially save TfL £100-£200m per year.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News