Why Byron’s a punchline in Britain – yet a god in Greece

Athens, where I have spent much of my adult life, is home to a Byron Street, and a neighbourhood, Vyronas, also named after the poet. Unique among the philhellenes who aided in the struggle for Greek independence, Byron even has a public statue in Athens in his honour: a bare-chested female personification of Greece, crowning the poet with a palm branch. All are reminders of the unalloyed admiration in which he was and is held in Greece – where he died 200 years ago, in April 1824 – in contrast to the Anglophone world, where his reception has ever been more uneven and “complicated”.

Scandals which dogged him in his lifetime – such as his incestuous relationship with his half-sister Augusta – still dominate many readers’ ideas about him today. The British Library’s online potted biography introduces him as “the 19th-century bad boy”, and his name tends to be followed by “mad, bad, and dangerous to know”, in Lady Caroline Lamb’s phrase (though one suspects she was at least partly projecting).

This Anglophone blind-spot is nothing new. Writing 60 years after Byron’s death, Swinburne, attacking Byron’s “pretentious and restless egotism”, found it “curious” that he nonetheless had so many significant “admirers in foreign countries”. The condescension sometimes extends even to his poetry. Imagine dismissing Byron to Russian speakers, for instance, when Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin would not exist without the model of Don Juan! Yet I recently read a review of Andrew Stauffer’s delightful new Byron: A Life in Ten Letters in which the reviewer rounds on Byron: “The author probably makes too high a claim for the poetry – Byron surely was no more than a first-rate second-rater.” Reading this, I gasped aloud, before taking to social media. (“Byron will have the last laugh,” I typed into the void, furiously.)

Nowhere, of course, is Byron more admired than in Greece. As is possibly an occupational hazard for an English-speaking expat poet living in the country, I have an ever-burgeoning shelf of books by or about Byron. But one of my most treasured remains a Greek children’s book I had bought as a joke: Lord Byron: The Supreme Philhellene (1999), by Petros Bikos, part of a series about the Greek War of Independence.

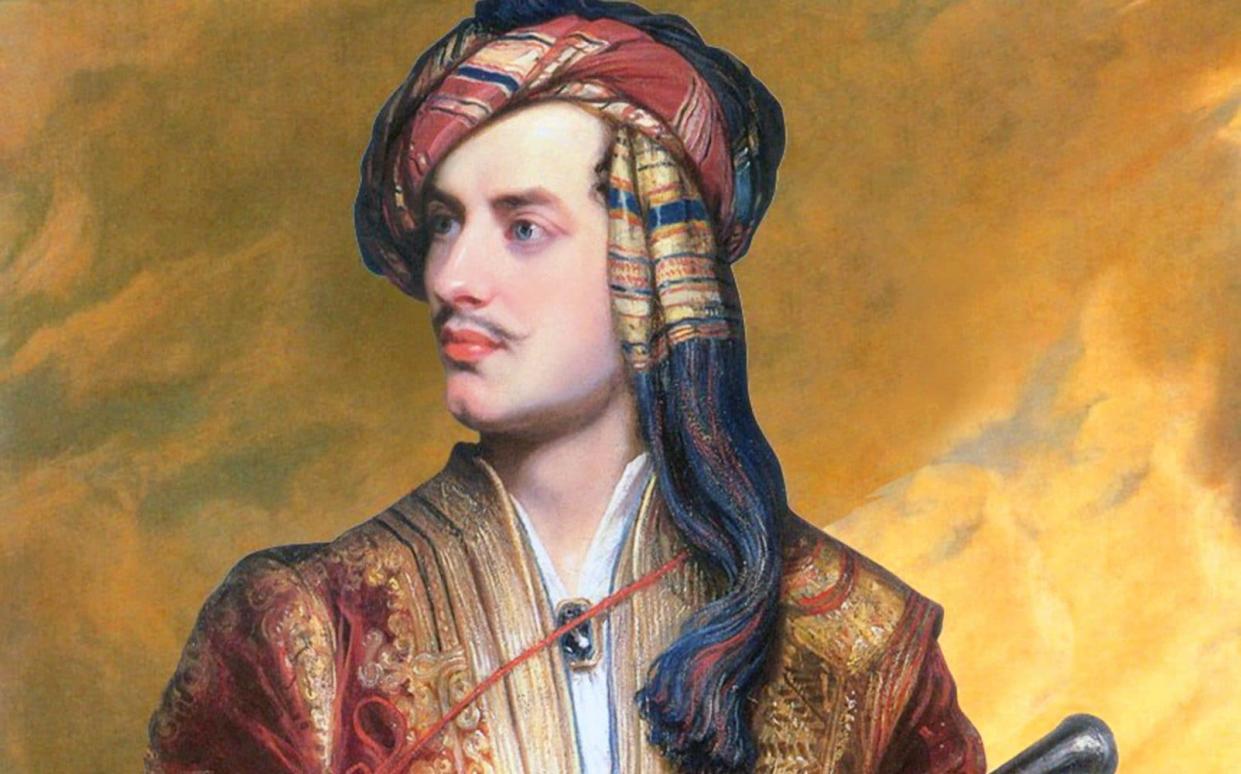

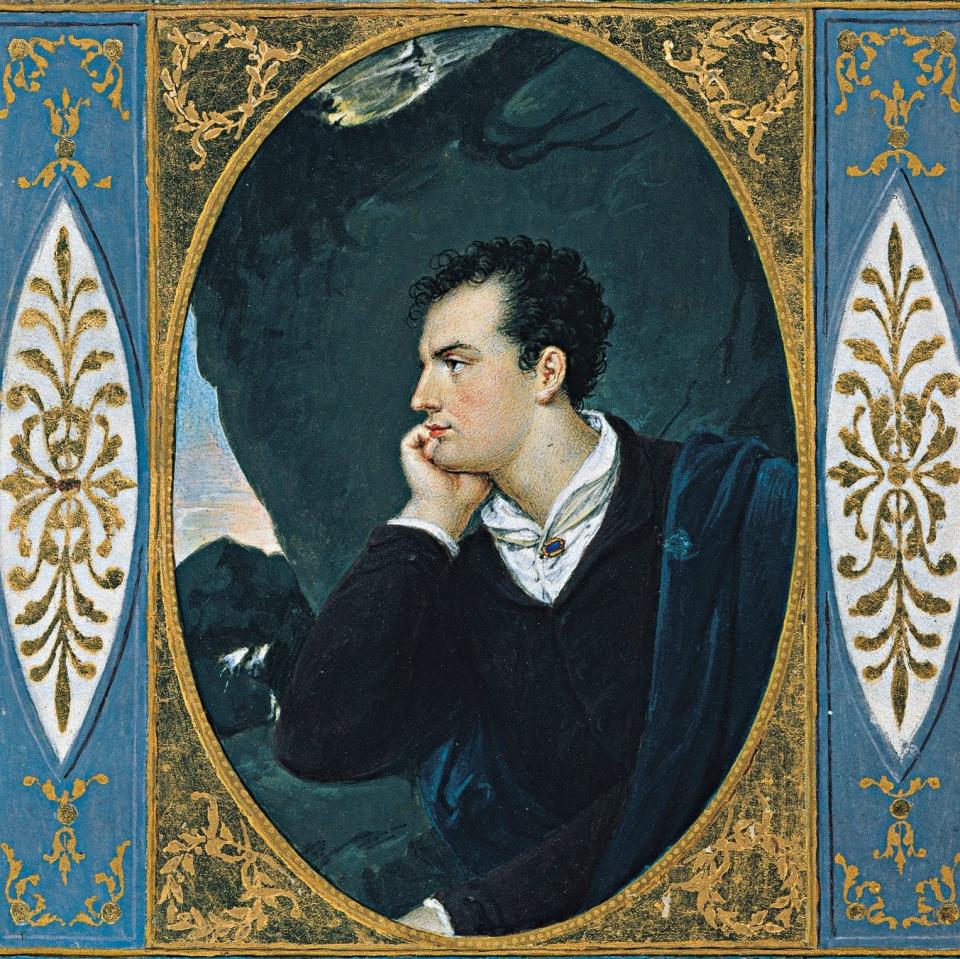

The Byron on the cover little resembles the figure we normally imagine – the glamorous Byron, say, of Thomas Phillips’s 1813 portrait, arrayed in exotic Albanian dress. The illustration on the cover has rather something of the impish mirth of a middle-aged Roger Moore playing 007; perhaps most strikingly, he has reddish blond hair and light blue eyes. The thing is, though, Byron did have “auburn hair”, according to contemporary accounts. In effect, I realised, Byron was regularly depicted as darker (and maybe “darker”) than he was.

I’ve learnt other things from the book, or it has changed my perspective. The reasons it gives, for instance, for his leaving England have less to do with scandal than being misunderstood. The book admits that he “challenged the conservative society of his time” with his “ephemeral erotic adventures”, but maintains that England’s “puritanical” mores were weaponised against him by his enemies. The book claims it was instead Byron’s fiery maiden address to the House of Lords, invoking the human rights of the loom-breaking Luddites (an exhilarating and radical speech slightly to the left of Bernie Sanders) that made him a class traitor to the English aristocracy. It gives oppressive grey skies as an additional reason for Byron to leave England for good.

The book focuses on incidents that many English-language Byron biographies skim over, such as his terrifying voyage to Missolonghi from the “United States of the Ionian islands”, a British protectorate, and officially neutral. Byron’s two ships carried papers and significant cash in Spanish dollars that would belie their neutral flag. Had Byron been captured by the Ottoman fleet, he might have been executed, or taken prisoner. In the end, Byron’s ship evaded capture, as well as shipwreck during a violent storm, but the cargo ship carrying Byron’s secretary, Pietro Gamba, was seized.

As Stephen Minta describes it in his On a Voiceless Shore (probably my favourite English-language book on Byron), “She [Gamba’s ship] was taken into custody with all aboard, and her captain was on the point of being beheaded. Then, by one of those coincidences that are plausible only in life, the Turkish commander suddenly recognised the captain as the man who had once saved his life in the Black Sea.” It’s a scene that would not be out of place in a Pirates of the Caribbean film.

No matter how pro-Byron an English-language writer is, they often can’t resist a jibe about the helmet. Upon setting out for Greece from Italy, Byron had three Homeric-type helmets fashioned to his own design. The teasing starts with Mary Shelley, who wrote to Leigh Hunt: “Helmets so fine were never made to hack.” Even a Byronophile such as Roderick Beaton (in his enlightening book Byron’s War) can’t resist comment. Of Byron’s reception in Missolonghi – where he was given a hero’s welcome by a crowd of perhaps 8,000 – he writes, “If one of the three helmets that he had had made in Genoa was upon his head, nobody present was ever so tactless afterwards as to mention it.”

Two of these helmets are, I believe, lost. One, that somehow washed up in Boston, is now displayed at the National Historical Museum in Athens. In the rooms of the museum, Byron’s black helmet, set alongside other moving personal effects such as the camp bed upon which he died, is among the most sombre and understated of fancy hats. Portraits of splendidly moustachioed warriors in turbans and crimson tasselled fezzes glower down from the walls, and General Theodoros Kolokotronis’s own Homeric helmet, scarlet with gilded bronze decoration and plumed with horsehair, is larger and glitzier.

Another aspect of Byron that provokes a smirk among Anglophone writers is his death, not in battle but from illness, as if the whole expedition were a celebrity publicity stunt gone wrong. Even the redoubtable Dame Mary Beard can’t resist some mild Byron-baiting. Writing of Byron’s first visit to Athens, when he “evidently divided his time between deploring the state of modern Athens” and “scribbling poetry”, she adds that, “Byron had not yet decided to parade himself as the champion of Greece and Greek freedom – a cause for which he would eventually die, from fever rather than cannon fire, at Missolonghi.”

Byron would have no doubt preferred death in action to being exsanguinated in the name of medicine. (“If Death comes in the shape of a cannonball and takes off my head, he is welcome to it,” he is reported to have said, “don’t let the blundering doctors bleed me.”) No one in Greece doubts his genuine commitment to the cause. Byron raised morale in Missolonghi’s besieged revolutionary outpost, helped – with Alexandros Mavrokordatos (incidentally, Mary Shelley’s Greek tutor) – tip the balance towards a legitimate government and away from civil-warring chieftains, and was pivotal in securing the loan from the London Philhellenic Committee that would bankroll the war; beyond this, he made his personal fortune available for the cause. Whether it was a £4,000 advance (perhaps £400,000 in today’s money) to the Hydriot navy whose pay was in arrears, or providing for Greek refugee families on Ithaka out of his own pocket, or organising the release of two-dozen Turkish prisoners in an effort to avert atrocities on both sides, Byron consistently put his money where his mouth was.

Then, as now, the West tended to pay more attention to a foreign struggle after high-profile Western deaths. In 1824, it was hard to get more high-profile than Byron. His rousing funeral oration, delivered by Spiridon Trikoupis (later Greece’s first prime minister) over Byron’s coffin – upon which were set a laurel wreath, a sword and, yes, the notorious helmet – was widely disseminated in Europe. The poet Dionysios Solomos, upon learning of Byron’s demise, is said to have started improvising his “Ode on the Death of Lord Byron” on the spot. Byron even entered the traditional songs of the klephts (the mountain brigands), something that no doubt would have tickled him. A hundred years after his death, the Greek poet Kostis Palamas would coin the word “Byronolatry”, and would address him in one of his poems: “If you lived a Dionysus, you died a Messiah.”

If that seems over the top – Byron would have thought so – consider the symbolic timing of his death, four months after his Christmas Eve arrival in Missolonghi. He died on April 19, the day after Orthodox Easter Sunday. In Greece, Easter, by far the most important holiday of the Church calendar, is celebrated with fireworks and raucous exuberance. All loud sounds (including celebratory gunfire) had been forbidden while Byron lay on his deathbed, with patrols enforcing the ban, though a thunderstorm shook the skies. But the festivities were suspended in Missolonghi even after his death; instead of exultation at the Resurrection, shops were shut, and an official mourning period of three weeks was proclaimed for Byron. This effective cancellation of Easter, in Greece, is mind-boggling to contemplate.

My Greek children’s book ends with head-shaking sorrow that Byron’s body was refused burial in Westminster Abbey (his lungs and spleen were placed in an urn in Missolonghi, but lost during the fall of the city), and concludes on the note that, “Lord Byron was honoured not only in England. He was honoured, and maybe more so, also in his second homeland, Greece.” It’s a book full of breathless hyperbole, but in this statement, anyway, it is arguably not wrong.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News