Why Ed Asner’s anti-American politics put the boot into Lou Grant

When the death of the actor Ed Asner, at the age of 91, was announced, his peers were quick to pay tribute to a man who they praised as being both a great thespian and politically engaged. Ben Stiller wrote on Twitter that Asner was “an icon because he was such a beautiful, funny and totally honest actor. No one like him.” And on the other side of the political divide, the conservative actor James Woods wrote that “he was the sweetest man and it was an honour to know him.”

The obituaries all mentioned his most famous role, that of the plain-talking journalist Lou Grant, and most acknowledged his latter-day career success as the voice of the protagonist Carl Fredricksen from the Pixar animated film Up. Yet it was his work as an activist and liberal firebrand that defined Asner personally, and would have considerable career repercussions, for good and for ill.

After Asner began a career in theatre and television in the Sixties, he made his debut as the Grant character in the Mary Tyler Moore Show in 1970. Initially, Grant was the news director of the fictitious WJM-TV station in the show, with Moore’s character Mary Richards as his associate producer. In the context of a light-hearted situation comedy, Asner managed to bring emotional truth and surprising vulnerability to a character who could easily have been a stock “gruff veteran journalist with a heart of gold” stereotype. The show explored issues such as Grant’s alcoholism, unsuccessful relationships and Jewish faith, albeit with a light touch, and it made Asner synonymous with the image of an upright, principled man of integrity, which is how he viewed himself, both onscreen and off.

It was therefore unsurprising, and unprecedented, that after Asner left The Mary Tyler Moore Show in 1977, he reprised the Grant character in a drama, simply called Lou Grant, in which he played the City editor of the Los Angeles Tribune. This series was much more heavily geared towards social issues, including everything from illegal immigration to institutional corruption, and was an enormous hit.

Much like his peer and fellow high-profile liberal Alan Alda, who achieved his own renown in the television series of M*A*S*H, Asner himself took on many of the characteristics of his crusading character. In July 1980, he led many of his fellow actors in the Screen Actors’ Guild strike, which boycotted that year’s Emmy awards. Of 52 performers nominated for awards, only one turned up.

In Asner’s case, it was both brave and foresighted to ally himself with so political a cause. The following year, he was elected to the presidency of the SAG, succeeding the character actor and union activist William Schallert. It was not long until Asner began to use the platform that his high-profile role had given him to stray far beyond his apparent brief in the entertainment industry and to offer his views on a variety of topics. Although he claimed that he had previously remained silent for fear of being blacklisted, it did not take him long to become one of the most prominent left-wing voices in America, and an outspoken critic of the Reagan presidency.

This did not play well within the often small-c conservative environment of network television. His bosses and colleagues might well have wished that he had not described the anti-gay activist Anita Bryant as “one kooky lady” when he addressed a gathering of newspaper executives, and likely sighed when he stood on the steps of the US state department, announcing his intention to donate $25,000 to Mexican doctors working in El Salvador, a country that America was then at war against. He said “I stepped out to complain about our country’s constant arming and fortifying of the military in El Salvador, who were oppressing their people.”

The result – aside from receiving bomb threats and requiring armed guards – was that conservative and pro-Reagan actors such as Charlton Heston called for him to be forced out of his position as head of the SAG, leading a chastened Asner to claim that he had made “a slight goof” and “an honest mistake” and clarified that he had been speaking as a private citizen, rather than in his official capacity.

Nonetheless, his perceived anti-American remarks had their own professional consequences. Although a petition calling for him to be removed as SAG president was unsuccessful, the Lou Grant show was cancelled by the CBS Network, citing low ratings. Asner responded that the show had consistently ranked within the top 10 programmes in its timeslot, and that the real reason for its termination was that his political stances had become an embarrassment, not least to the sponsors and advertisers who removed their support.

Certainly, although he had won four Golden Globes and five Emmys for his performance as Grant in both its comedic and dramatic iterations, Asner struggled to find high-profile leading roles of the same calibre again in his career, suggesting that he had exercised his first amendment-approved right to free speech too enthusiastically and frequently for comfort.

He remained SAG President until 1985, when he was replaced by Patty Duke, much to the chagrin of Heston, who had himself created an unofficial splinter group of the SAG, called Actors Working For An Actors Guild. Unlike Asner, who was a staunch believer in the power of a trade union, Heston sought to distance himself and his fellow actors from this dangerously left-wing initiative. Asner, always ready with a witty quip, simply remarked that “Chuck hasn’t recovered from playing Moses. He gets his authority straight from Mount Sinai.”

And he continued to wage war against his much-detested President, too, who had called his support for El Salvador “very disturbing”. Asner remarked in 1985 that Reagan “has made us the global bully and he’s done it with lies and deception”, and that his administration had aided “mercenaries and soldiers of fortune”. He went on to say that “I don’t enjoy knowing the lies. I was brought up believing that the presidency was a very honourable office. I would prefer being able to trust the guy. But I can’t and I don’t.”

Asner’s scepticism and anti-authoritarian streak did not lessen with age. He was a supporter of the 9/11“Truther” movement that suggested that the events of September 11 were a conspiracy, and appeared in a 2004 video where he remarked “Can it all be an accident? Four planes destroying four different buildings? What happened to the black boxes?” He railed against the “miscreancy and possible criminality” of the Bush administration, and openly wondered, in the absence of further terror attacks, “was it Osama? Could there have been great culpability and criminality in the United States?”, before calling for a full enquiry into the events. Perhaps not coincidentally, Asner had appeared as FBI agent Guy Banister in Oliver Stone’s 1991 film JFK, itself a conspiracy thriller about the truth behind the Kennedy assassination.

By the end of his life, thanks to his vocal role in Up and an appearance as Santa Claus in the Will Ferrell film Elf, Asner had become the American equivalent of that nauseating designation, a “national treasure”. He endorsed Obama in 2008, narrated a documentary about Aids deniers and gave his name to the Ed Asner Family Center, which supported special needs individuals in America. Yet he was by no means finished as either an actor or an activist.

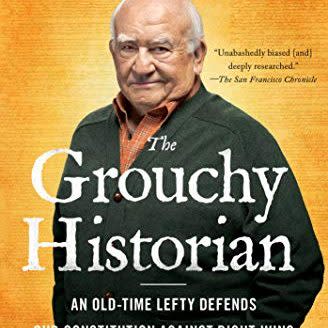

In 2017, he published the inimitably titled The Grouchy Historian: An Old-Time Lefty Defends Our Constitution Against Right-Wing Hypocrites and Nutjobs. Although he had, in his late eighties, retired from overt political demonstration, he stated in an interview that Trump had falsely stolen the presidency, and said “it’s like we got swallowed by a black hole, and I don’t know if we can reach the surface again. This country has become so riven by this president. It’s chaos time. Trump is breaking the back of America.”

Although Asner was much beloved for his portrayal of the upstanding and dedicated Lou Grant, a character that he was synonymous with all his life, he was all too aware that, in real life, it was harder to win hearts and minds through nobility and speeches than it was on television. He remarked in 2017 that “there is no man on a white horse coming. It’s up to each and every one of us, in whatever way we can, to fight for progressivism or at least stabilize what we’ve got.” Sometimes, his unusual way of demonstrating his activism caused controversy.

He expressed a desire to urinate on a Fox News producer in 2012, after being caustically described as “a radical left-wing actor, and to make a point in a 2017 interview about Harvey Weinstein, he asked a female journalist for a kiss, as he quipped “I'm sure I've been guilty at times of using my overpowering masculinity to beg for kisses.”

The awkward joke fell flat, and led to outrage on social media. Yet Asner was no stranger, throughout his long career, to being criticised for things that he had (or had not) done. As he once said, “To my knowledge, there is no blacklist. But there is a mindset, even among liberal producers, that says ‘He may be difficult so let's avoid him.’”

It was this difficulty that made him the man, and the actor, he was, and why he is now being remembered with such fondness by millions, even if, like Woods, their politics stood poles apart from his. Ed Asner remained a man of principle and integrity, even if these were sometimes misguided, and his death removes one of the last great liberal actors from the film and television industry. It is the poorer for it.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News