Why a royal touch could make the Sycamore Gap saplings worth more than the original tree

It was the superstar sycamore that brought joy to thousands in the north east of England every year, until two vandals took a chainsaw to it on one fateful day last September.

On Wednesday, a second man denied being responsible for the felling of the tree that once stood in the Sycamore Gap in Northumbria. His co-accused did not attend the hearing at Newcastle Crown Court but the court heard he continues to deny sawing down the tree. The pair will stand trial on Dec 3 this year charged with criminal damage to the tree itself and to a section of Hadrian’s Wall that stood beside it.

The enormous sycamore had been poised in its spot for more than three hundred years, and thankfully a small handful of seedlings and buds were rescued by the National Trust, later incubated at its conservation centre at the other side of the country in Devon.

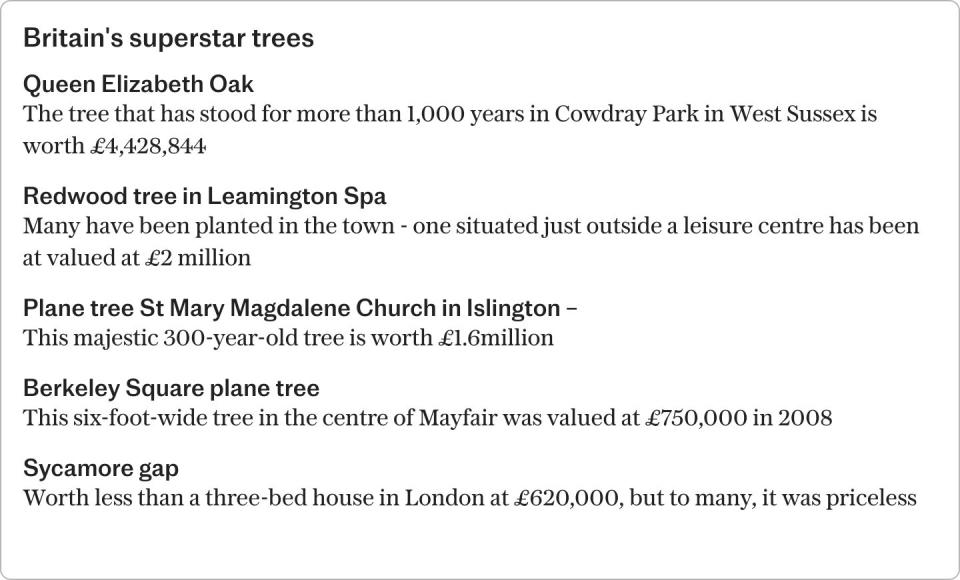

A prosecutor explained to Newcastle Magistrates’ Court last month that the sum assigned to the tree, which, at £622,191, was valued at even less than an average three-bedroom London house, was calculated using a system called Capital Asset Value for Amenity Trees (CAVAT for short).

The tool has been used by local governments since 2003 to put a monetary value on trees that are deemed an asset to their environments. By its measure, the Sycamore Gap’s saplings that have now been replanted by the King himself in Windsor Great Park, and by Judi Dench at the Chelsea Flower Show, could one day grow into trees worth millions of pounds.

“CAVAT works by what it would cost to make an equivalent replacement for the tree,” says Christoper Neilan, the tree surgeon who devised the system some 20 years ago. The point of it is not to suggest that beloved trees are interchangeable, he explains, but rather to calculate “realistic compensation where trees are damaged or have to be felled”.

This seemingly clinical tool is not the only one used to generate price tags for trees. One other example is Treezilla, a citizen science project devised to showcase the ecological value of trees and forests. This database points out how trees work to stop floods, suck in carbon and improve air quality in polluted urban areas – and according to Treezilla, £14 million is saved from local authority budgets every year by Britain’s hardest-working trees.

CAVAT meanwhile is used to determine how much it would cost to “replace” a tree in aesthetic terms – and the Sycamore Gap case is the first to consider the purposeful felling of one of Britain’s ancient “veteran” trees.

This task of calculating the beauty value of a tree seemed comparatively simple to Neilan when he first considered how to price up a tree back in the 1980s. There was existing precedent for this sort of measure in British law, he explains, with courts having used “pre-replacement” measures to calculate the financial cost of criminal damage or other offences, including in some cases where trees had been damaged or lopped down.

It’s all a matter of numbers, and how exactly this system works might sound absurd to lay people. First, CAVAT practitioners – typically tree officers for local councils – measure the diameter of a target tree’s trunk to determine its “base value”; fatter trees are more valuable, slimmer trees less so.

“There’s various maths behind that to make it accurate,” says Neilan, “but a very large tree such as the Sycamore Gap tree should come up with a very large base value.”

This idea comes from valuation systems used in America, Neilan says, with each species of tree having a different price tag based on how much they cost to grow inside a nursery.

The Sycamore Gap’s seedlings could one day have a similar base value to their parent – which would have been hefty, given it stood proud at 50 feet tall and just shy of a metre wide. Under CAVAT the saplings as adults would also get bonus points for being planted by famous individuals, in places of note and in memorial of Northumberland’s great sycamore.

Once this basic sum is determined there are a number of other factors that affect a tree’s final value, the most important of which is the human population surrounding it. The CAVAT system attempts to value trees based on their contribution to “public amenity” rather than as property, a guide for tree officers states, making them more akin to swimming baths or schools than paintings or statues.

Trees that are seen by large numbers of people on a daily basis therefore are given a heftier price tag. For populations of up to 20 people per hectare, such as in rural Northumberland where the Sycamore Gap tree stood, the tree in question retains its basic value.

But trees in London or other big cities, where there are more than 120 people living in a given local authority per hectare, can see their value increased by 250 per cent. Neilan recalls one grand, ancient tree at a churchyard in Islington that he believes would have been “getting on for a million” were it formally valued, despite it being far less famed than the Sycamore Gap tree.

CAVAT documents dictate that trees “that make the greatest contribution are those that may readily be seen and appreciated”. Despite its dramatic position atop a glacial dip, and next to Hadrian’s Wall, the Sycamore Gap tree was actually not all that easily visible – though since its appearance in the 1991 film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, it has been photographed as at least as many times as any other Hollywood star.

Neilan, meanwhile, has valued a plane tree in Berkeley Square, in London’s West End, at around £750,000. There are a number of large plane trees in this park but “I was asked to check the value of a particularly large one,” Neilan says. This valuation was carried out some fifteen years ago, meaning that this tree would be worth £1.1 million in today’s money. “The tree would have been even more valuable, except it had at some point lost a big limb to damage,” Neilan adds.

After taking damage into account, trees can be valued more or less highly for having “positive” or “negative” attributes: ancient trees like the Sycamore Gap tree get a triple-point boost over younger trees when they have extra special features.

Flowers, fruit and types of bark all make a tree more valuable, as does the tree “being integral to or enhancing a designed landscape, avenue, or garden”. So-called “favourite” trees as well as those deemed landmarks – such as the Sycamore Gap tree – are also valued more highly under CAVAT.

Even an ancient tree is deemed to be worth less, however, if it has thorns, or provides food for troublesome wildlife such as “undesirable bird species”.

Not all tree experts agree with using the CAVAT system to put a price tag on the Sycamore Gap tree, or any ancient tree. The system was primarily devised to value urban trees, the sorts that might typically be at peril from vandalism, building works or reverse-parking cars, and has not usually been applied to those in rural areas.

For this reason, and given all the measures involved in a CAVAT assessment, it’s likely that some of Britain’s surviving ancient trees – which don’t always stand in areas of natural beauty, but rather in car parks and town squares – could be deemed much more valuable than the Sycamore Gap tree should they ever be felled.

Midlands-based tree expert Ian McDermott recalls having valued a redwood tree outside of a public building in Leamington Spa at £2 million, for reasons including its awesome size and high visibility. “This particular tree seemed to predate the proper introduction of redwoods into the UK,” McDermott says, another fact that contributed to its enormous valuation.

Jordan Walker, a tree warden coordinator for West Sussex council, said that the Queen Elizabeth Oak – which has stood in Cowdray Park for almost a thousand years – could be valued at almost £4.5 million using the CAVAT method; a fact of its longevity and its enormous trunk, making it incredibly hench at 42 feet wide.

Several other neighbouring trees in this park could be deemed as worth more than £1m were they ever to be formally priced, based on their trunk size alone, he adds. But as Walker rightly points out, “due to the history, management and natural beauty of this tree, it is simply invaluable”.

“No monetary based valuation system can realistically account for its true value which is unique to each person who has visited the tree,” Walker adds, “and this is arguably the same for any veteran or ancient tree”.

But if we do have to measure, the Sycamore Gap tree’s progeny will surely be some of the most highly valued natural artefacts to ever have grown.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News