Why Slade were Britain’s first – and possibly last – great working-class rock band

At the start of 1973, Slade guitarist Dave Hill welcomed a film crew from the local news programme ATV Today to view his new £40,000 home in the West Midlands market town of Solihull. Lounging in front of a strategically placed gold disc, he told presenter Brenda Holton that fame was “great”, and that “anybody who says it’s not good are idiots”. The segment ended with a shot of a young teacher at the girls’ school next door gamely attempting to shepherd away a class of 20-pupils each of whom was chanting his name.

During this same period, the marriage of bassist Jim Lea to the childhood sweetheart he had met at school failed to endear him to in-laws who were not wholly keen on their daughter getting hitched to a rocker. About this, he seemed confused. On the one hand, Lea “wanted to show ’em” what was what by driving up to their front door in his brand new Rolls Royce. On the other, in what looks rather like a betrayal, none of his bandmates were invited to the wedding.

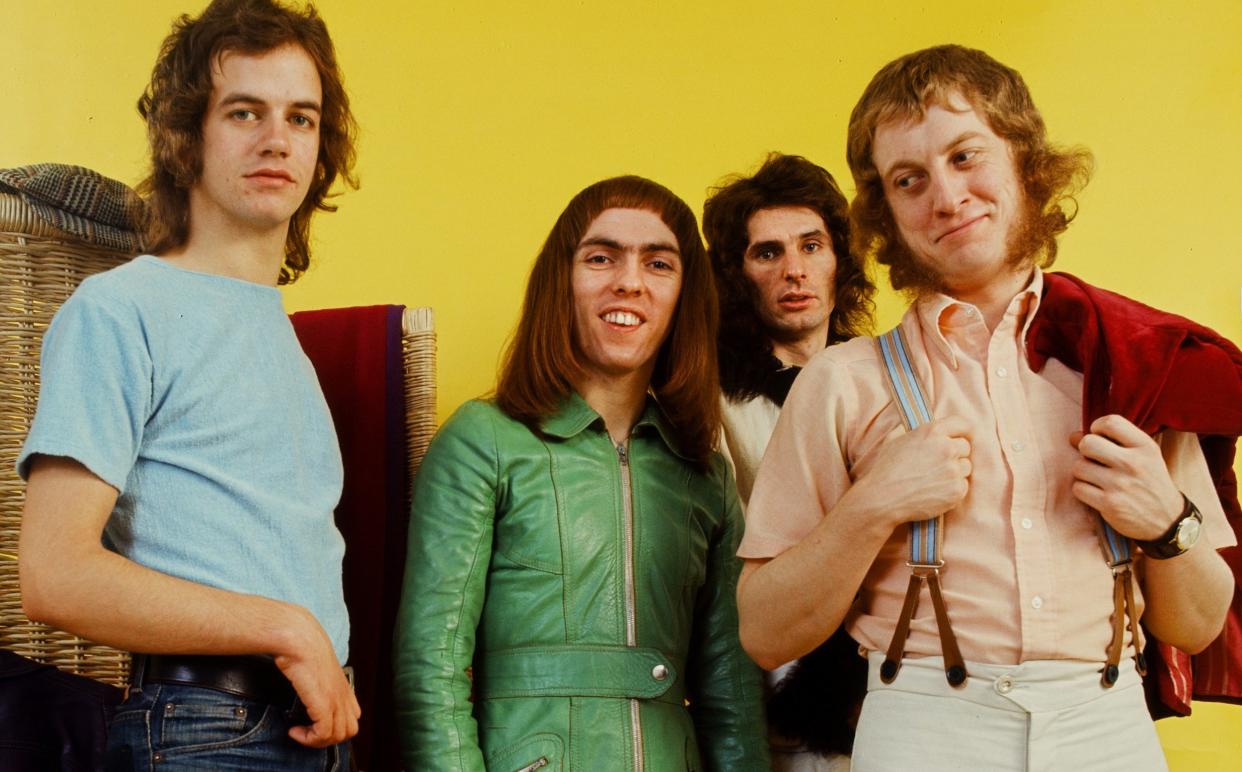

These details, at once minor yet piercingly vivid, appear in a new book that well understands the transformative power of pop and rock in an age when records ruled the world. One of the joys of the informative and thoroughly readable new book Whatever Happened To Slade?, by Daryl Easlea, is the context in which it places both the band’s music as well as the young men who made it. The 1960s may have swung, at least for some, but the early seventies were a drag. For the British working class, rocking and rolling was the fastest, and surest, way out of the gloom.

Few did this more raucously, or more authentically, than Slade. Louder than a beano to Blackpool, the band – then known as the N’ Betweens – made their bones in 1968 by working in a club in the Bahamas at which they performed four sets per evening on a bill that included a belly dancer and a snake-charmer. Each night they slept on four beds in a single room that contained a fridge and a toilet, all provided by a benefactor who went by the name King Sniff. “It sounds horrendous,” Hill says, rightly enough, “but I think that was what made the band.” Certainly, it was the first time any of them had seen a fridge.

When at last they began writing their own songs – Lea composed the music, while mutton-chopped frontman Noddy Holder penned the lyrics – the sound of what Daryl Easlea calls “bovver rock” resonated across the nation. Viewed today, the band’s catalogue – their entire being, in fact – looks very much like a bridge in a working-class neighbourhood that links the loveable Beatles to the feral Sex Pistols. Not that Slade was the kind of band who would ever be as tricky as John Lennon, you understand, let alone Johnny Rotten. “Sure, they’re the new Beatles,” wrote the American critic Lester Bangs, “[only] they’re all Ringo.”

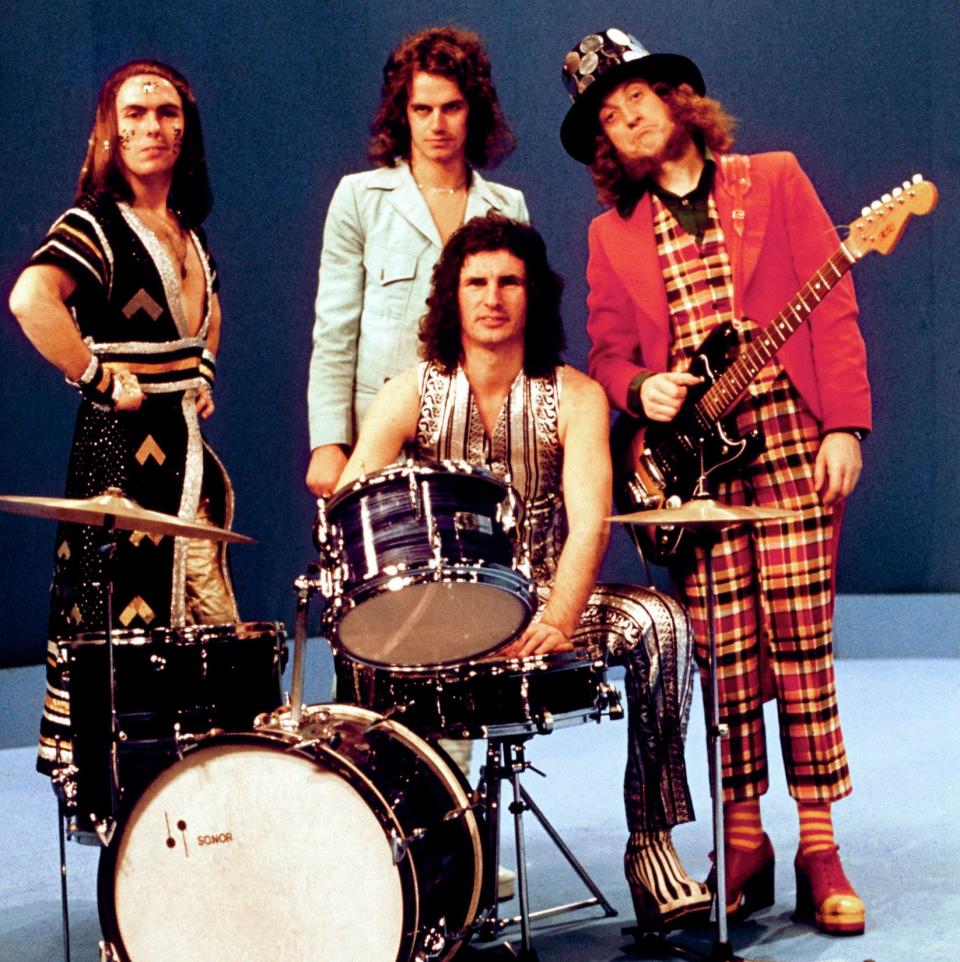

Maybe, but the class consciousness that rang through every note the group played was innate rather than incorruptible. Attempting to find an angle amid the busy world of urchin artists making the apparently effortless leap from working men’s clubs to Top Of The Pops, Slade at first allowed themselves to be moulded into Britain’s first skinhead band. When this failed, as it was always bound to, they at last found their groove by tearing open the dressing-up box with such abandon they looked like an explosion in a vomit factory. In 1972, Dave Hill broke one of his legs falling over on platform heels onstage at the Liverpool Stadium.

But worry not, by then they had the wind in their flares. A string of chart-topping singles bearing the misspelt titles Coz I Luv You, Take Me Bak ‘Ome, Mama Weer All Crazee Now and Cum On Feel The Noize seemed purpose-built to speak only to a young audience that was experiencing the first convulsion of national decline since the end of the Second World War. Even the evergreen (not to mention piercingly irritating) Merry Xmas Everybody – a million-seller written in 1973 after Lea’s mother-in-law claimed Slade would never issue a song as popular as White Christmas – couldn’t resist referring to the festive period in the kind of shorthand guaranteed to aggravate the elders.

And let’s not underestimate that kind of power. Because while Roxy Music had the cred, and Bowie had the star-power, the union of Hill, Lea, Holder and drummer Don Powell was that rarest of birds: a group who were the precise equal of their audience. As David Hepworth put it in his book 1971, “Nobody came away from a Slade show without understanding that they had been entertained and entertained by a band who didn’t look down on them.”

Because they couldn’t, could they? They were them. Whenever Slade entertained the London-based press, as they did for the first of two hometown concerts at the Civic Hall, in Wolverhampton, in the summer of 1973, after-show parties were held at The Trumpet, a local boozer. “It was what we were about,” explained Holder to the journalist Mark Blake. “Didn’t want to hire the Dorchester and put on a posh do with canapés, you’d have some black pudding and be happy. That was our thing.”

These parties went on until seven in the morning. “Here is us,” the singer explained, employing the kind of grammar for which Slade were justly celebrated, “taking [the press] to a spit-and-sawdust one-room pub, effing and blinding constantly… and they absolutely loved it. Everybody would get pissed out of their head and then get on the coach back to London and write up the gig. It was what we were about.”

That was our thing. It was what we were about. Unfortunately for them, though, soon enough – far sooner than they deserved, for sure – Slade would learn that what they were about was fame rather than success. With the band flogging themselves senseless in an attempt to crack the American market, at home their presence on the singles chart began to diminish.

At a BBC Radio 1 fun day at Mallory Park race circuit, in 1975, John Peel watched as Noddy Holder “strode unnoticed” through a crowd hollering for the Bay City Rollers, the new kids on the block. “[Holder] must have thought, ‘Well, that’s the end of that, then,” was how the DJ put it.

Certainly, mismanagement had taken root. Whereas fellow fading-star Marc Bolan wasted no time inserting himself into photo opportunities with a punk crowd that had doubtless been built in part by Slade labour, Noddy Holder and Dave Hill remained out of the frame. It didn’t matter that no less a descendant than Joey Ramone claimed to have “spent most of the early 1970s listening to [live album] Slade Alive! thinking to myself, ‘Wow – this is what I want to do. I want to make that kind of intensity for myself.” It didn’t even matter that he never managed it.

Indirectly, however, Slade would at least get some kind of due when a pallid version of Cum On Feel The Noize, by the Californian quartet Quiet Riot, propelled its parent album, Metal Health, to the top of the US chart. Thirteen years later, in 1996, a roaring version of the same track, this time by Oasis – another band who stood eye-level with their audience – at last paid the song the respect it so clearly warranted.

Today, Dave Hill is the only original member of a version of Slade that appears in the kinds of clubs in which the group began more than half a century ago. “I may be with a different set of blokes,” Easlea reports him as saying, “but the actual experience [of playing live] is still the same.” He once suffered a stroke in the middle of a gig. Regaining consciousness in hospital, wired to machines, he started crying. “I felt I’d let the band down,” he said.

Whatever Happened To Slade? When the Whole World Went Crazee, by Daryl Easlea is published by Omnibus Press

Yahoo News

Yahoo News