Why is the Trump trial jury anonymous? The brief and imperfect history of anonymous juries in the US

A version of this story appeared in CNN’s What Matters newsletter. To get it in your inbox, sign up for free here.

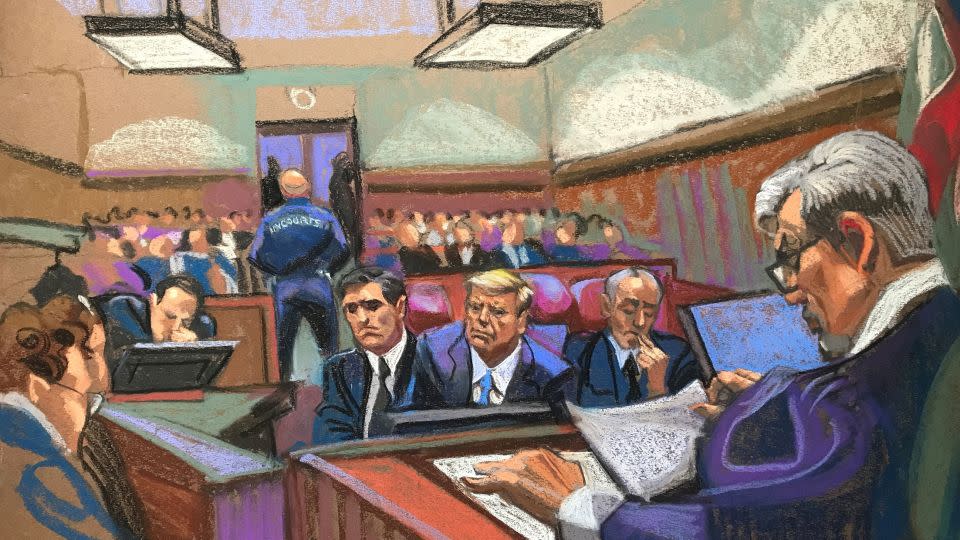

While former President Donald Trump is spinning conspiracy theories about people infiltrating the jury in his hush money criminal trial, the judge in the case is finding it difficult to protect jurors’ anonymity.

Anonymity for juries like the one being formed to hear charges in New York against Trump is supposed to add a layer of protection for jurors doing their civic duty. Once reserved only for cases involving violent criminal enterprises, the practice is becoming more common. It’s usually employed for high-profile cases but also at will by judges in some states. Rules vary.

The concept of anonymous juries is still relatively new; the first in US history was empaneled in New York in 1977 for the trial of Leroy “Nicky” Barnes, a drug kingpin known as Mr. Untouchable, according to The New York Times. Barnes, famous for avoiding conviction, caught the attention of then-President Jimmy Carter, who told the Justice Department to take special care with the case, which yielded a guilty verdict.

Even the lawyers in that case weren’t permitted to know the identities of the jurors, a step further than the precautions in place for the Trump trial in New York. Both prosecutors and Trump’s defense have been poring over the social media profiles and pasts of potential jurors in Judge Juan Merchan’s courtroom.

Merchan issued an order in March agreeing with prosecutors that most information about the jurors would be sealed. Trump’s lawyers did not disagree, according to the order.

A separate Trump-related jury, the one that found Trump liable for sexual abuse and defamation of E. Jean Carroll, was fully anonymous – like the one that convicted Barnes – and the identities of jurors were not known to lawyers on either side.

CNN’s Jeremy Herb recently wrote about how Trump has acted around juries before this current case.

In this hyperconnected social media age, anonymity is hard to achieve. One juror who had been sworn onto the panel on Tuesday was excused by Merchan on Thursday after she said her anonymity was blown.

“Yesterday alone, I had friends, colleagues and family push things to my phone questioning my identity as a juror,” the former Juror No. 2 told Merchan.

Merchan admonished the press for publishing information that could identify jurors.

“We just lost what probably would’ve been a very good juror,” Merchan said in court. “The first thing she said was she was afraid and intimidated by the press.”

Read more about Merchan scolding the press from CNN’s Hadas Gold.

Trump, ever trying to chip away at the justice system that is prosecuting him, seeded a new conspiracy theory by posting a quote on social media, attributed to Fox News host Jesse Watters, that “undercover Liberal Activists” were trying to get on the jury.

Set aside the fact that there is no evidence to support this claim – and consider that the prosecution needs every juror to agree with them to get a guilty verdict, while Trump just needs one to vote for acquittal to result in a hung jury. Meanwhile, a special hearing on whether Trump has violated a gag order for his continued social media attacks is set for next week.

When anonymous juries go wrong

Maybe Trump remembers one of the most infamous, anonymous jury incidents, featuring another famous New Yorker, the mob boss John Gotti.

The anonymity of jurors in that case from 1987 allowed the jury foreman, who just so happened to have organized crime connections, to contact Gotti and, in exchange for bribes, guarantee a hung jury.

The informer who turned on Gotti, Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, also told authorities the juror, George Pape, had been bought off. Pape voted to acquit Gotti, but so did the 11 other jurors. The contaminated acquittal stood since the Constitution protects against double jeopardy, according to a New York Times report at the time. Gotti later went to prison after a subsequent conviction on different charges.

Clearly there’s a massive difference between a major push by the federal government to go after organized crime in the 1980s with racketeering charges and Trump’s prosecution for the Class E felony of falsifying a business record in furtherance of campaign violations.

But the unyielding support Trump commands from his supporters and the violent things they will do on his behalf, like storming the US Capitol, suggest this is the type of case where anonymity is clearly warranted – although the practice of anonymous juries is in tension with the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution, which guarantees a public, fair and speedy trial by an impartial jury.

What we know

Merchan told news outlets to better refrain from reporting details that could unmask the jurors, like physical descriptions, and prohibited them from including elements that are on a jury questionnaire, like their places of business.

There is known, public information about the jurors – their genders, professions, family situations and more – that it’s reasonable to think they could be unmasked by determined internet sleuths or loose-lipped acquaintances.

Investigations into the jurors are also being conducted in real time during this process. Trump’s defense was scrolling through old social media posts and asking jurors about them.

Prosecutors are looking for flaws with jurors. Another juror, a Puerto Rican grandfather who had said he finds Trump “fascinating and mysterious,” was also dismissed Thursday. The exact circumstances of his dismissal are not clear, but prosecutors informed the judge their review of criminal records showed a person sharing the man’s name was arrested in the 1990s for tearing down political advertisements.

A jolting experience

Thursday’s court session ended with a full, 12-person jury being seated. These jurors will be asked to take on the weight of sitting in judgment of a former and maybe future president.

“Jurors show up, and a lot of times, they don’t think they’re going to end up being selected for whatever reason. And so when they go through the process, as soon as they’re sworn in a panel, that can be pretty jolting,” the jury consultant Alan Tuerkheimer told CNN’s Omar Jimenez in an interview on Max. “That can be for a regular case. So think about this case,” he added.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com

Yahoo News

Yahoo News