William Friedkin on The Exorcist, battling Gene Hackman and his many ‘sexual liaisons’

This interview first ran in 2013, and has been republished following the death of William Friedkin, aged 87

William Friedkin, Hollywood’s most combustible director, has tried therapy only once. The session took place on April 11, 1972, the day after he won the Oscar for best director for The French Connection. He was 37 years old and the toast of Hollywood, but he woke up so depressed, he couldn’t get out of bed. His business manager sent him to a Beverly Hills psychiatrist, who took notes while Friedkin sat and talked for an hour. “I was making up stuff. Complete lies. The guy was a total stranger. Why would I tell him anything about what’s really going on with me?”

Friedkin walked out, never to return, even after suffering a heart attack from stress in his early forties. “I’ve read plenty of Freud. A lot of his stuff is insightful, but overreaching. I don’t need to know any more about myself. I know what’s wrong with me.”

Hurricane Billy’s tantrums and blow-ups are, of course, the stuff of legend. His take-no-prisoners antics while making classic films such as The French Connection and The Exorcist put even hubris-drenched rivals such as Peter Bogdanovich and Michael Cimino to shame. When Friedkin wasn’t frequenting prostitutes or firing people (70 people on one movie alone), he was slapping actors to provoke a reaction or letting off real shotguns to get the right sound effect. No question, he was the wild man of Seventies cinema, and it was a densely crowded field.

Forty years and not a few flops later, he has once more resumed the process of digging deep into his personal history. The result is a cracking 475-page memoir, The Friedkin Connection, which is as blunt, outrageous and unpredictable as the man himself.

He admits he had no faith in Gene Hackman when they made The French Connection. He wanted Jackie Gleason for the lead role and the pair butted heads constantly: “His outbursts [onscreen] were aimed directly at me… more than the drug smugglers.” And after auditioning 1,000 girls for The Exorcist, Friedkin picked “normal, happy” Linda Blair because she understood the concept of masturbating. “Have you ever done it?” Friedkin asked the 12 year-old sitting with her mother. “Sure,” she shot back. “Haven’t you?”

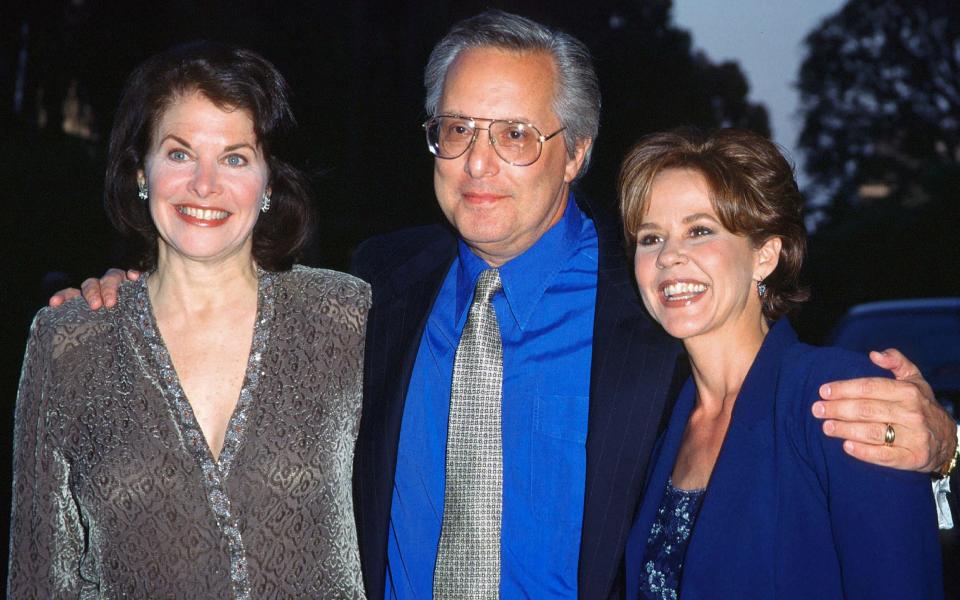

We meet at his home in Bel Air, where he lives with his wife of 21 years, former Paramount chief Sherry Lansing. It’s in a leafy canyon rich with movie history. Delores Del Rio used to live down the road, as did Sidney Poitier and Judy Garland. Friedkin lives right on top of the hill in an imposing Italianate villa behind a set of Xanadu-sized gates.

He steps out to greet me looking tanned and coiffed in his trademark tinted shades. With his striped dress shirt and gaberdine slacks, he could easily pass for a Colombian drug lord; only his big, spongy trainers say otherwise.

As fans of his DVD commentaries or Q&As will know, Friedkin has a wonderfully bombastic manner. He is foul-mouthed, outrageous, funny and admirably passionate, even at 77 years old. He’s also pretty much the same guy whether he’s addressing an upscale New York audience or a lecture room of film students. “You don’t know who Billy Wilder is? Get the f--- outta here!”

At the mention of the Twilight movies, he shakes his head in disgust. “F------ Twilight. ‘We wanna be filmmakers because we saw New Moon!’” We go into the living room and settle by a flickering fireplace. He is genteel civility personified to start with, but at the first mention of modern cinema, his familiar declamatory manner bubbles up.

“There were some really fine films in the Seventies, like The Parallax View, that dealt with the human condition and moral complexity. That’s disappeared. Now, it’s all about guys in spandex suits flying around saving the world. There are a number of good films around today. [Pause.] I can’t name them… But it’s no longer for me, I can tell you that.” He presses an electronic clicker and a houseboy appears in a Union Jack T-shirt and silver shorts to take orders for coffee and croissants.

“For me, the golden era of film is the Forties and Fifties. MGM musicals are the backbone of American movies. Nothing made in the Seventies, with the exception of the Godfather films, compares to what they did in the Forties. There’s no All About Eve, Citizen Kane or The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

“If I have any regrets, it’s that I didn’t come up in the studio system where a director could do three to four films a year. Like Michael Curtiz. Some were good, some were bad, one or two were masterpieces like Casablanca. I haven’t made 20 films in 50 years. And it’s not like I took time off, either.”

One thread that emerges in his book is how hard it is to get a movie made even in so-called golden eras of moviemaking. “As you might imagine, Sean, that’s been a staple reaction to my book – how difficult it was. It wasn’t difficult at all! Frankly, the problems of a film director sustaining their career are of little import to the great scheme of life. A job where you have to punch in every morning, that’s difficult.”

He spreads out a napkin and bites into a croissant. “Whatever so-called struggles I write about are nothing compared with what Vincent van Gogh went through. He did over 3,500 works – drawings, sketches, watercolours, oils – and couldn’t sell a painting. He produced all this work and had no recognition.” He looks appalled at the thought that any trace of self-pity might have seeped into his book. “I hope my book doesn’t sound like Mein Kampf.”

There’s no danger of that, unless I missed the chapter where Adolf Hitler goes scouting for locations at New York’s S&M gay bars wearing only a jockstrap. Friedkin did just this while researching 1980 thriller Cruising. “I wasn’t bothered that much, to be honest,” he told biographer Nat Segaloff in 1990. “If I was John Travolta, I might have had some problems. But I was just another fat Jew in a jockstrap.”

Friedkin grew up poor on the North Side of Chicago, the only son of Russian immigrants. “We had a one-room apartment, but I didn’t know we were poor until I left high school. Television was the miracle in our homes.” He remembers his parents had a very loving relationship, but the most formative incident that emerges in his book is a violent one.

After being bullied for a year by a kid at Hebrew school, Friedkin finally snapped and attacked him back. “Something entered my consciousness that I wasn’t going to take this anymore. I put him in a headlock like I’d seen on wrestling on TV and banged his head on the sidewalk. I remember the distinct sensation of wanting to kill this guy. I don’t know what it was that prevented me.”

He says all this with an air of total equanimity. One can understand why director Michael Mann asked him to play Hannibal Lecter in his 1986 thriller Manhunter. “I thought he was putting me on,” says Friedkin. “I said, ‘You see me as Hannibal Lecter?’ He said, ‘I see you exactly as Hannibal Lecter. You don’t appear to be psychotic, but you are.’”

Friedkin’s memoir sheds a new light on the many great scenes of bullying and intimidation in Friedkin’s work, such as Gene Hackman’s non-sequitur interrogation in The French Connection: “When was the last time you picked your feet? You ever been to Poughkeepsie? You been there right? … You took off your shoes, put your fingers between your toes and picked your feet, didn’t you? Now say it!”

Friedkin left high school without graduating and got a job in the mail room at a local television station. Colleagues remember him as a cocky kid, with a touch of the con man about him. His father may have been a modest man (he worked selling clothes), but many of Friedkin’s uncles were volcanic-tempered scoundrels. One was a cop who shot one of Al Capone’s henchmen in cold blood, then shot his own hand to make it look like self-defence.

At the television station, young Billy worked his way up to studio floor manager before making a documentary about a man on death row. This proved to be his ticket to Hollywood, where he paid his dues making a Sonny and Cher film and adapted stage plays such as The Boys in the Band. He is rightly proud of his 1968 adaptation of Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party, but the performances are brimming with fully realised menace. Tellingly, it’s packed with bullying and intimidation, a strain that has come full circle with his most recent films, Bug and Killer Joe.

The perilous tension between good and evil that so fascinates Friedkin found its most famous expression in The Exorcist. Everyone remembers the head-spinning and projective vomit, but it’s also a film of immense craft. Take the scene where Linda Blair enters the party and urinates on the rug. It’s not the urinating that makes the scene so powerful as the subtle reaction shots of the shocked guests.

Armed with the memoirs, one can’t help noting it’s the film’s psychiatrist who gets demonically grabbed by the balls. But any attempts to knit these elements together psychologically are shot down with a no-nonsense bark. “When I wrote this book, I was not seeking self-analysis. We’ve all been given these two great gifts of life and love. And they’re both ephemeral. You can’t do anything about it.

“You meet somebody and you fall in love with them. I could meet the same person and have no interest in ever seeing them again. Love is a mystery as is all of life. I don’t bull---- myself. If you can translate that into self-analysis, fine.”

He certainly doesn’t shy away from acknowledging his professional mistakes. The most pivotal is the moment he turned down Steve McQueen for his proposed remake of The Wages of Fear, released in 1977 as Sorcerer. McQueen loved the script but wanted to shoot closer to Los Angeles, so he could be near new love Ali MacGraw.

Friedkin, riding high on the success of The Exorcist, was determined to film in South America, so he wound up making the film with Roy Scheider. The result is something of a lost masterpiece, but it tanked horribly. “The most beautiful landscape in the world,” says Friedkin, “doesn’t mean s--- compared to a close-up of Steve McQueen.”

To be fair, Sorcerer was released in the United States one week after the opening of Star Wars, which reset American cinema back to comforting fantasy. It was a brutal irony for Friedkin’s downbeat epic about four reprobates transporting nitroglycerine through the jungle; the evil wizard of the film’s title is fate, specifically the cruel version.

“It’s something that has haunted me since I was intelligent enough to contemplate it – the fact that you can walk out of your front door and a hurricane can take you away, or an earthquake, or something falling through the roof. It’s the idea that we don’t really have control over our own fates, neither our births nor our deaths.”

For all his candour, the one glaring omission in Friedkin’s book is any mention of his sexual exploits or ex-wives. “In the context of this story, they’re peripheral,” he says. I make the case that sexuality is a big part of his movies – any exploits would be illuminating. “I don’t really think, Sean, that you need to know about my various sexual liaisons. Or that anyone else needs to.”

It’s a weird moment of impasse; he’s not being prudish, just thematically decisive. “I did write about them. I filled a hundred pages of Moleskine notebooks with my one-night stands, my affairs. But I decided they didn’t belong in a professional memoir. First of all, these are real people we’re talking about. Many of them were enjoyable. Some were abject failures.”

Which only makes it more interesting, no? He gives a shrug of agreement. “My wife said to me when she read the pages, ‘Of what purpose is this in a memoir? Of what purpose is this other than to titillate?’”

The great thing about all this is that he doesn’t seem remotely offended by my prurience. “Had I written about my three other marriages,” he explains, “all of which failed, it would have been only from my perspective. I wasn’t about to go to these women and get their perspective. I’m still in touch with Jeanne [Moreau, his second wife]. The point is, I never see them. It’s because I have nothing in common with them, frankly. And probably didn’t at the time. I could not provide a sensible reason why I married these women.”

I look bewildered at this last statement. Moreau was the sad-eyed beauty of French cinema. Lesley-Anne Down, his third wife, was the British bombshell from Upstairs, Downstairs. Both are seriously attractive women. “Yeah, but that’s just superficial,” he says. “The thing is, in the case of my marriages, it takes two people to f--- up a marriage. It wasn’t simply the fault of these women that I lost interest in them and realised they were insignificant relationships. Which is how I look at them right now – as being insignificant.”

That’s quite a harsh thing to say. “It’s true. I see them as blips.” Moreau at least introduced him to Proust, which fills two shelves in his teeming office. “Like many others, I mark my life as before Proust and after Proust. You find parallels in Proust to all sorts of ideas and themes in your own life if you’re willing to give yourself to him.”

Then he relents and gives me a saucy story that was cut from the manuscript. It was during a location scout for Sorcerer in the Dominican Republic, where he wound up on the beach at night having sexual intercourse with the mistress of a local colonel. (A colonel, one should add, who had recently shot a man in a restaurant for being a communist.)

“She was very persuasive,” he says. “After a few minutes of bliss… well, more than a few minutes, I hear the click of rifle bolts and screaming in Spanish. I open my eyes to six rifles pointed at my head. I thought, ‘It’s all over. They’re going to say I was a communist and kill me on the f------ beach.’ Then this woman stood up, still naked, and yelled at them. Words to the effect of, ‘Get your f------ a---- out of here or I’m going to have the colonel take your heart out!”

He takes a sip of his demitasse of coffee. “I continued to see her, obviously. Just not on the beach.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News