Without true friends or allies, Theresa May’s downfall was inevitable

All political careers end in failure. Not all end in a punishment beating. The apparently imminent departure of Theresa May as Tory leader has seen a brutality rare even for the British Conservative party.

She was crowned with acclaim in 2016, and set the task of honouring the result of the Brexit referendum. In the 2017 election, she won almost as high a share of the popular vote as Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair ever did, a fact converted into failure by Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system.

She fought to steer a necessary Brexit compromise through a divided Commons. Her party’s response to her efforts should be an awful warning to whoever succeeds her. Panicked by Brexit and riven by ambition, the Tories junked their most valued political weapon, loyalty to the leader. They rubbished her.

Rarely does politics turn on personal failings, but May’s have been her undoing. British politics, Alexis de Tocqueville noted, mimics the club not the mob. Sensible leaders form retinues, protective packs. May’s inability to make friends or court allies deprived her of the natural support she needed in her tortuous enterprise. She seemed wooden and inflexible, even in seeking the compromises she so desperately needed.

Related: May close to abandoning Brexit bill amid growing cabinet backlash – as it happened

May’s only club has been her husband, Philip. She was otherwise alone, and by this week seemed eerily bereft of kindly advice. Being bundled out of office by erstwhile supporters is peculiarly painful. It was so for Thatcher and Heath, and even for Macmillan and Eden before them. For the Tories, leadership recalls that of the Roman empire, determined by coronation tempered by assassination. It is the epitome of men behaving badly. Nothing has changed since it went over from choice by cabal to election by MPs in the 1960s, and then by party members in 1998. All that can be said is that there is probably no better way.

Boris Johnson: ‘Whoever leads the Tories will have to negotiate a Brexit deal with Brussels and fast.’Photograph: Luke Dray/Getty Images

Labour finds it much harder to get rid of unsatisfactory leaders, but both systems are preferable to America’s constitutional fixed terms, with removal dependent on impeachment. It is better, when political accidents happen, for the captain to be ditched and the voyage to resume with most of the crew still in place.

More important, May’s departure will make no difference to the realities of the Brexit saga. However inept the messenger, the message remains the same. Some version of May’s present deal is inevitable if economic relations with the EU are not to go over the cliff. The next Tory leader will still have to forge a compromise capable of passing the House of Commons. The two sides of a divided political community have to be brought together.

A customs union and single market, however tentatively described, are clearly in the nation’s trading and therefore economic interest. If the polls are any guide, they are also the nation’s wish. A customs barrier, whether “virtual” or otherwise, round an offshore island and through the Irish countryside would benefit no one but bureaucrats and police officers. The same goes for a ban on migrants.

The Brexiters’ thesis that some trading El Dorado awaits Britain “in the rest of the world” is mendacious cynicism. The nation is not nearly as divided on this as hard Brexit’s champions like to maintain. May’s transitional compromise may yet come to be regarded as her most durable achievement if only because, as Thatcher would say, there is no real alternative.

This week’s European elections are a complete red herring. The likely victory of the Brexit party will not signify a collapse in support for Britain’s two main governing parties. These elections are not for a government. They are an answer to a stupid question, asked incessantly by Nigel Farage: do you approve of how the big parties have handled Brexit? It would take a strong stomach for anyone to go to the polling station and put a cross against that.

For the past two years, the House of Commons has reached one clear decision. It has voted overwhelmingly against leaving the EU without a deal on customs and borders. Whoever leads the Tories – be it Boris Johnson, Jeremy Hunt, Michael Gove or anyone else – will have to take this as given. They will have to negotiate a Brexit deal with Brussels and fast, and that deal will have to be a version of the one that the Commons has three, if not four, times rejected.

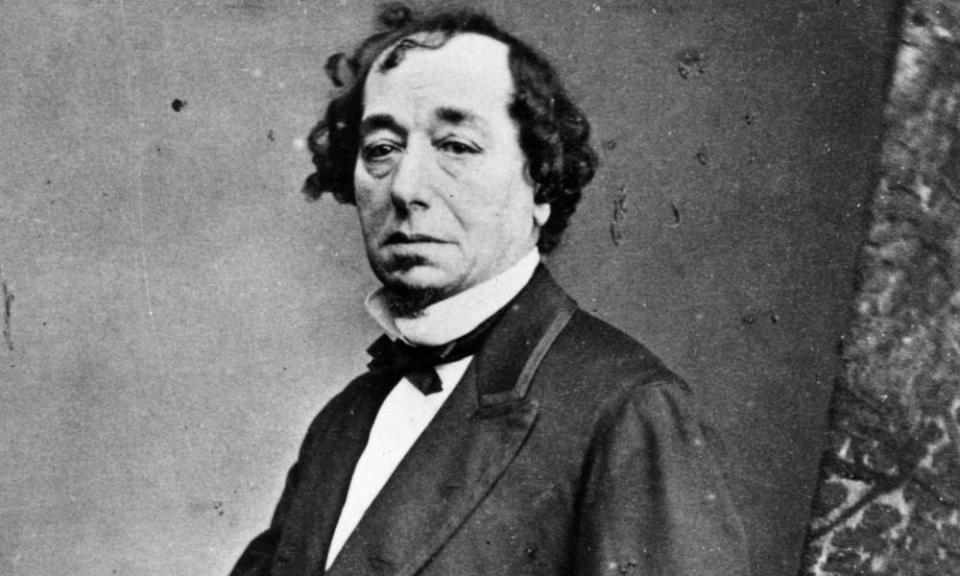

‘To secure Brexit, candidates for the Tory leadership will need the hypocrisy of a Disraeli.’Photograph: General Photographic Agency/Getty Images

At this point, May’s failings come into focus. Machiavellian doctrine ordains that power may be gained by principle, but it is retained by pragmatism. The arts used to win power are not those for keeping it. The political scientist David Runciman reminds us that, while hypocrisy may be a failing in ethics, in politics it borders on a necessity.

To secure Brexit, candidates for the Tory leadership will need the hypocrisy of a Disraeli or a (peacetime) Churchill. They must be ready to rat on their principles, turn against friends, deceive the media, and do so with populist panache. Somehow, May’s plan B must be recast to mobilise a soft-Brexit coalition across the Commons. The backwoods hardliners must be bribed or isolated. If all this sounds right up Johnson’s street, he may yet be soft Brexit’s best bet. As Runciman notes, the essence of a Disraeli is not to rat on your principles but to have none in the first place.

One guardian of this process remains in place. The Commons must accept that if compromise cannot be found, it will have failed to honour its 2016 bargain with the electorate. That must require a new mandate, either through another referendum, or through returning to square one, revoking article 50 and a general election.

As for Johnson, he can be left to the tender mercies of the Conservative party. It is good at devouring its own.

• Simon Jenkins is a Guardian columnist

Yahoo News

Yahoo News