'Woman Of The Hour' Actually Does Dramatize Violence — But That's Not Its Problem

Anna Kendrick both directs and stars in "Woman of the Hour," a mixed-bag drama that examines how serial killer Rodney Alcala was able to hide in plain sight on "The Dating Game."

TORONTO — A year after the Netflix series “Dahmer — Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story” drew questions around the exploitative nature of depicting the serial killer’s crimes, there comes a film that promises to be different.

A synopsis for “Woman of the Hour,” actor Anna Kendrick’s directorial debut, states that it intentionally doesn’t dwell “on the gruesome details that often preoccupy true-crime tales.” The film’s introduction at the Toronto International Film Festival, where it debuted last week, doubled down on this sentiment.

Well, it’s not entirely true. The movie, which in part dramatizes real-life serial killer Rodney Alcala’s murder spree throughout the 1970s, very much does rehash some of his horrific acts — and that begins quite early in the film. Audiences more critical of these kinds of images might be troubled by how frequently Kendrick returns to them. That’s fair.

Especially considering what those acts were. They include Alcala (played by Daniel Zovatto) bashing a woman’s head into the floor of her apartment until she breathes her last breath and strangling a pregnant woman to death on the ground.

As traumatic and disturbing as these moments are to watch, they aren’t what brings down “Woman of the Hour.” They’re actually important to understanding what Alcala did while hiding in plain sight by employing, like Dahmer, charm and an unassuming demeanor to maintain a veneer of comfort for his victims.

Still, “Woman of the Hour” isn’t a great movie. It’s a film about a lot of things that don’t always come to fruition. Kendrick has been outspoken about the ways in which she, and many other women, have had to navigate male abuse and gender dynamics in and outside of romantic relationships. And her first directorial effort is a reflection of that.

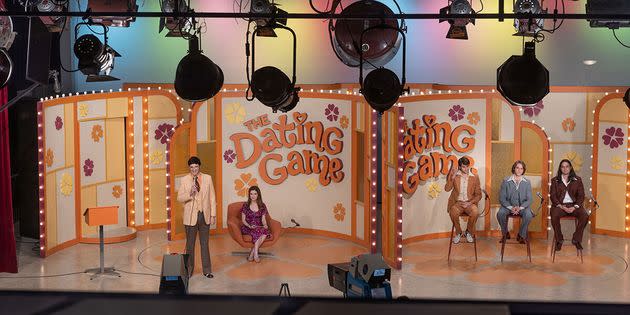

That’s where it actually excels. “Woman of the Hour” uses a show as innocuous-seeming as “The Dating Game” to illustrate the lengths a woman like Cheryl Bradshaw (Kendrick) feels compelled to go to in order to be both entertaining to a conventional TV audience in the ’70s and appealing to single men of the era.

Kendrick has been outspoken about the ways she and other women have had to navigate male abuse and gender dynamics in and outside of romantic relationships. "Woman of the Hour" is a reflection of that.

There’s a lot to take from that. As “Woman of the Hour” depicts, Bradshaw was yet another unsuccessful actor trying to make it in Los Angeles when her agent landed her the gig of being the oh-so-cute bachelorette asking questions of three eligible (and hidden from her view) bachelors on “The Dating Game.” For those unfamiliar, the show was like a live-action version of Tinder.

In other words, it was demoralizing, a crapshoot, and yet intensely popular.

Contestants like Bradshaw were tasked with dumbing themselves down and asking scripted questions like, “What’s the best time?” to which the men would respond something like, “Nighttime, because that’s when it really gets good,” with a smirk. And after Bradshaw and other women would select a bachelor based on the answers they provide, they would go out on a date as the prize.

It was silly, fun and in some ways a sign of the time, but then there are also modern dating apps that aren’t much different. In “Woman of the Hour,” Kendrick really focuses on the ways that women contort themselves to seem attractive, palatable and permissible to men, and even to a live TV audience.

As Bradshaw, Kendrick uncomfortably deals with the men on “The Dating Game.” In the film’s script, by Ian MacAllister McDonald, we get to see a version of Bradshaw who changes the inane questions to more substantial ones that make the bachelors shift in their seat, as well as the guys in her real-world dating scene who manipulate her into sleeping with them.

This dramatization, while effective in the way it brings attention to the rampant sexism inherent in something like a televised dating show, isn’t entirely true to real life. It doesn’t appear Bradshaw ever actually did that. Maybe she didn’t want to, maybe she didn’t feel she could. It’s hard to tell which.

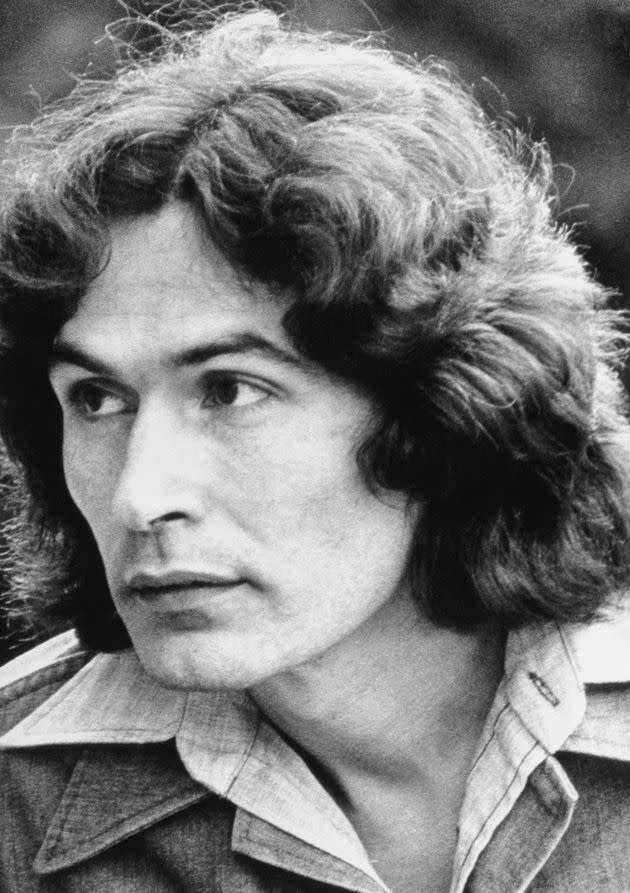

Rodney Alcala at age 36 in 1980, when he was sentenced for the rape and murder of 12-year-old Robin Samsoe. He is chillingly portrayed by Daniel Zovatto in "Woman of the Hour."

“The Dating Game” always looked like a well-oiled machine where the woman was merely an entertaining prop to satisfy a hungry audience. So, of course there was a script.

But in taking us backstage to see Bradshaw being asked by host Jim Lange (Tony Hale) to change into something sexier, or to laugh a lot to show that she’s cute and fun, “Woman of the Hour” goes even further. It’s clear that Kendrick wants us to see that this type of female performance to appeal to male favor has been long systemic.

It’s just that in Bradshaw’s case, one of her bachelors is Alcala, someone who’s similarly skilled in the act of performance to appeal to the opposite sex, so much so that she chooses him as her date. That dichotomy is interesting and deeply disconcerting, and underscores a still-relevant real-world issue.

Kendrick and her team also effectively portray chilling aspects of our social world. Like the way a simple date at a bar can turn into a regrettable sexual encounter or a frivolous appearance on a dating show can lead to coming face-to-face with a charismatic serial killer.

None of that is what makes “Woman of the Hour” a subpar film. Rather, it’s the way the movie is organized. It starts with the pregnant woman’s murder and frequently goes back and forth in time between the taping of the “The Dating Game” episode and another one of Rodney’s crimes — and in no particular chronological order.

While it was necessary to depict Alcala's violent nature in the film, Kendrick stumbles as she aims to piece that together with a far more fascinating examination of gender dynamics in romance.

The film begins with the murders in the late ’70s, jumps to the early ’70s, then back to the mid-’70s. Then, it ultimately gives us a postscript that goes well into the 2000s detailing the frustrating ways that law enforcement failed to act once Alcala was found out and after he committed many more murders. It feels unsatisfying and disorienting.

And it takes away from Kendrick’s fascinating premise that explores the less-discussed dangers inside what we consider romance, dating and companionship. All the “The Dating Game” scenes — including those with a female audience member (Nicolette Robinson) who recognizes Alcala’s hidden vileness from her own past encounter with him — are done so, so well.

But they’re interrupted by a continual effort to remind the audience of who Alcala really is, in a way that is flat, repetitive and incohesive. This makes the dating show sequences far more welcome, interesting and startling, even though the shocking significance of what they’re depicting has been known for decades.

Because they’re saying a whole lot more.

Like a few other directorial debuts at TIFF this year, Kendrick deserves praise for making a work of art that is curious and scratches the surface of an underdiscussed topic. It’s just that the execution could have used a bit more work.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News