World’s first ‘dengue dashboard’ could predict outbreaks months before they happen

Consulting the forecast before venturing abroad is a no-brainer for any tourist. But scientists hope that holiday-makers will soon be able to add a dengue radar to their pre-travel checklist.

The debilitating mosquito-borne disease has thrived across almost every continent this year, killing at least 5,500 people in the 20 worst-hit countries, according to new analysis from Save the Children – a jump of 32 per cent since 2022.

But as climate change pushes the virus into new territories, including Europe, researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) are developing the world’s first ‘dengue dashboard’ to track the pathogen’s spread in real time and predict where the disease might strike up to three months in advance.

The project was inspired by the Covid dashboards that enabled governments and individuals to assess and mitigate their risks during the pandemic, said Dr Oliver Brady, an assistant professor at the LSHTM who is leading the data project.

“I’ve spent decades working on dengue, and it still really bothers me that if I go online right now, there’s no one single source that shows what the current situation is, and which countries across the world are having epidemics,” he told the Telegraph. “I think the Covid pandemic highlighted how useful this tool could be for governments and the public.”

The dengue dashboard, financed with £430,000 from the Axa Research Fund, will initially track the virus across 50 countries, then gradually expand. It will also include a forecasting tool that will combine data including temperatures, rainfall and infection rates to predict how transmission will shift over the following two to three months.

Based on an initiative already rolled out in Vietnam, scientists say this will not only be useful for governments and researchers, but also locals and tourists.

“If you’re going on holiday, for example, we hope the dashboard can be useful for monitoring the situation that is occurring where you’re going to travel,” said Dr Brady. “Then we can link you to a whole load of resources about how to prevent mosquito bites and options for how to protect yourself.”

The dashboard, which aims to launch sometime next year, comes amid a record-breaking year for dengue transmission worldwide – driven by climate change, the El Nino weather phenomenon and urbanisation, plus the lifting of restrictions and travel rebound post Covid.

“The last year has been exceptional,” said Dr Brady. “We shouldn’t expect every year to get worse and worse … but the longer term risk is increasing, and we need to start making strategic decisions to reduce that risk.”

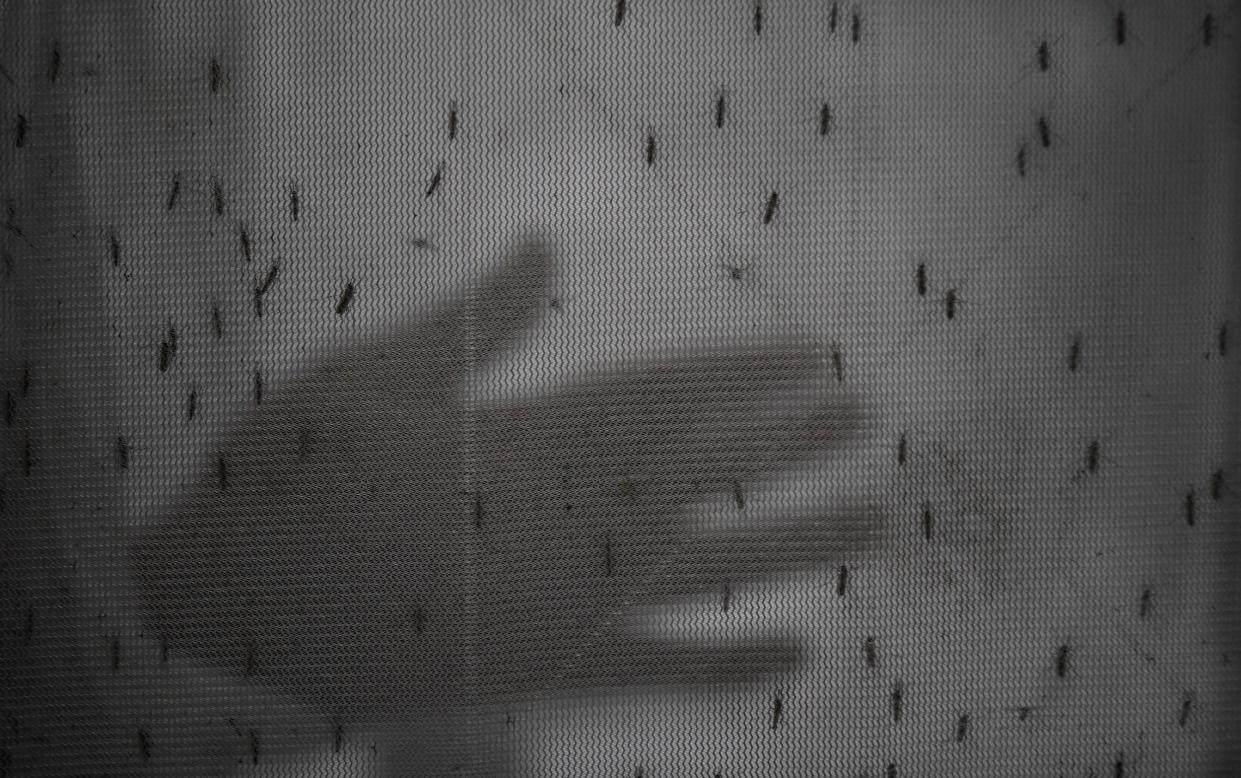

Globally, data on dengue transmission is patchy, partly because cases are generally mild and can be misdiagnosed. But according to the World Health Organization, some 400 million people are infected with the virus – dubbed ‘breakbone fever’ because severe joint pain can be one of the symptoms – each year, while at least 100 million become ill.

And although the death rate is generally low, the virus exacts a heavy toll on productivity and health systems, with some 500,000 people hospitalised annually and many more experiencing symptoms including fatigue and brain fog that can last for weeks.

“A Covid-style real time data dashboard which also includes genotypic information would definitely allow more efficient tracking of dengue outbreaks across the world,” said Prof Ruklanthi de Alwis, deputy director of the Centre for Outbreak Preparedness at Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, who is not involved in the LSHTM project.

“Dengue is still very much a neglected tropical disease with the largest case burden residing among low resource settings in tropical regions of the world. Therefore, real time dashboards, which are usually resource intensive, for tracking dengue outbreaks globally have been lacking so far,” she said.

This year, countries as diverse as Bangladesh, Burkina Faso and Peru have been especially badly hit, in epidemics that should “open the world’s eyes to what’s on the horizon”, according to doctors on the ground.

Evolving transmission patterns

Bangladesh, for instance, has faced its worst outbreak on record – with more than 1,600 fatalities since January and at least 300,000 confirmed cases, compared to 62,000 last year. It is likely that the true toll is 10 times higher, as only those who seek medical attention at public hospitals are counted.

“In October, hospitals were overflowing with dengue patients, especially in Dhaka [the capital] where there were more people than capacity,”said Dr Mohammad Shafiul Alam, a scientist in the infectious diseases unit at a health research centre in Dhaka called icddr,b. “We are now past the peak, but hospitals are still seeing many, many cases.”

He added that transmission patterns have also changed, increasing the threat posed by the virus.

Usually, dengue hits in seasonal waves – with cases virtually disappearing in the dry season. Although new infections are declining, Dr Alam believes it is unlikely to get to zero, “which means dengue has become a year-long condition in our country”.

And traditionally, the disease hits cities, where the Aedes aegypti that carries the virus thrive, but in Bangladesh the virus is increasingly spreading to rural areas, too. At several points this year, transmission rates have been highest outside Dhaka. Dr Alam puts this down to a rise in mosquito breeding sites across the country, and says the trend is unlikely to reverse.

But a steady stream of alerts from ProMed – a surveillance system that tracks infectious disease outbreaks across the globe – have highlighted that this issue is not confined to Bangladesh.

On the other side of the world, Peru has recorded more than 270,000 cases this year – almost four times the 74,000 infections confirmed in 2017, the last El Nino year in the country. At least 50 children are among those who have died.

Meanwhile in Africa, Burkina Faso has reported 50,000 probable cases and 511 fatalities, while countries including Mali and Sudan also seeing higher rates of transmission. In southeast Asia, Thailand has seen approximately 127,000 infections – more than three times the figure last year – and infections in Malaysia doubled to about 100,000.

“Climate change is playing a key role, with the vector being established in new areas and seasonality in endemic settings extending,” said Sophie Yacoub, head of the dengue research group at the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit in Vietnam.

Long-haul holiday-makers are not the only ones who may need to check a dengue forecast before going away. Invasive mosquito species are now established in three times more regions than a decade ago, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, and in 2022 71 people caught dengue within Europe.

Dr Brady said that the “big outbreaks” in Europe have arrived “much sooner than we would have expected”.

“I think we’ve underestimated the impact that climate is having on the northward shift of diseases like dengue,” he said, adding that more investment is needed in new vaccines, treatments and mosquito control measures.

“There’s very much a need to address the root causes of why dengue is spreading,” Dr Brady added. “So that’s about combating climate change, building urban environments that don’t provide breeding habitats for mosquitoes, and understanding the role trade and travel can have in spreading these viruses around the world.”

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security

Yahoo News

Yahoo News