The WWII Tokyo firebombing was the deadliest air raid in history, with a death toll exceeding those of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

On March 10, 1945, US Army Air Forces dropped nearly 1,700 tons of fire bombs on Tokyo.

The attack was an escalation of Allied air raids on Japan during World War II.

The attack killed up to 100,000 Japanese people and injured another million, most of them civilians.

In the opening scene of Hayao Miyazaki's latest semi-autobiographical film, "The Boy and the Heron," fighter planes drop bombs on Tokyo, setting the city ablaze.

The movie begins in 1943, two years after the Pearl Harbor attack that catalyzed US involvement in World War II. The Pacific War, as the theater of the war fought in eastern Asia and its surrounding regions was called, saw Allied powers pitted against Japan and resulted in millions of casualties on both sides.

Massive air raids over Japan, like the one portrayed in the movie, were key to the Allies' fighting tactics.

One 1945 air raid on Tokyo became the deadliest bombing raid in human history — its death toll exceeding those of the infamous atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that effectively ended the war later that year.

Operation Meetinghouse

In the early hours of March 10, 1945, 279 American B-29 bomber planes swept low over Tokyo, dropping close to 1,700 tons of incendiary bombs on the sleeping city below.

Code-named Operation Meetinghouse, the attack was an escalation of previous air raids on Japan, which had begun in June 1944. In those early attacks, the US Army Air Force relied on a precision bombing campaign targeting Japanese industrial facilities, but they were generally unsuccessful.

Gen. Curtis LeMay, whose unyielding and demanding leadership earned him the nickname "Iron Ass," threw the Air Force's tactics out the window. He replaced precision bombing with area bombing, and conventional bombs with incendiary ones.

LeMay chose the night of March 9 and the early hours of March 10 for its dry and windy weather, which could enable the fire to spread across the wooden structures of Tokyo most effectively.

History's deadliest air raid

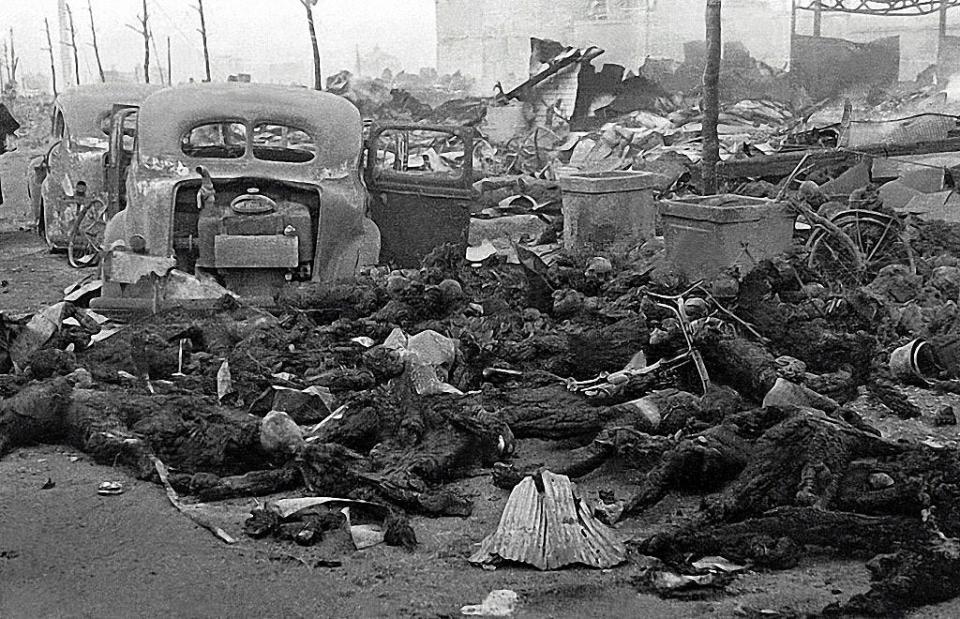

The air raid was swift, deadly, and merciless. The napalm inside the bombs devoured everything they touched, and the fires spread rapidly across the city.

Almost everything burned — the wooden homes, tatami mats, people's hair, clothes, and animals, according to eyewitness accounts.

"Babies were burning on the backs of parents. They were running with babies burning on their backs," Haruyo Nihei, who was then eight years old, recalled to CNN.

The smell of burning flesh was so strong that the bomber pilots had to put on oxygen masks to keep from vomiting.

Historical accounts detail how some of those who sought refuge in water were boiled alive, while others were trampled to death in the stampede to escape the firestorm. Most died from carbon monoxide poisoning and the lack of oxygen following the fires.

The attack killed up to 100,000 Japanese people and injured another million, most of them civilians, making it the most destructive single air attack in human history. One million people were left homeless.

(The estimated initial death tolls for Hiroshima and Nagasaki are 70,000 and 40,000, respectively, according to the US Department of Energy.)

Remembering the past

LeMay later acknowledged the brutality of the Tokyo air raids, though he stood by his decision.

"Killing Japanese didn't bother me very much at that time," LeMay is widely quoted as saying. "I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal."

After World War II ended, LeMay was hailed as a hero and continued to have a career in the military. He was made chief of staff of the US Air Force in 1961, and pushed for the bombing of nuclear missile sites in Cuba.

In Tokyo, a group of air raid survivors have since crowdfunded the opening of the Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Damage in 2002. The small museum seeks to commemorate the deadly raid and pay respect to those lost.

"I'm fearful of history repeating itself," Nihei, one of the survivors, told CNN in 2020.

Read the original article on Business Insider

Yahoo News

Yahoo News