Yoshida review – brilliant prints bleached of historical colour

It’s easy to see why a curator, or any art lover, might get fixated on the craft and beauty of Japanese woodblock prints, to the exclusion of any wider context. This genre, which first flourished in the 17th and 18th centuries, takes you into a bright, bold world away from cares – a “floating world” no less – and has been lovingly continued over the last century by different generations of the Yoshida family. Yet a telltale mistake in a caption and catalogue entry betrays this show’s dangerous disdain for the filthy mess of reality beyond art’s enchanted garden.

Looking at Yoshida Tōshi’s 1985 print Camouflage, in which two lethal, gorgeous tigers are almost completely hidden by a tangle of golden grass, you are cheerfully told by Dulwich Picture Gallery that it was inspired by his “travels in Africa in the 1970s and 80s”. One problem: tigers don’t live in Africa. A trivial mistake? Maybe. But it shows what this exhibition finds to be trivial: namely, everything outside its narrowly defined subject of one family’s artistic creations and the skills they have cherished.

Camouflage itself suggests the bigger, badder “tiger” of history this show ignores. Instead of an irrelevant trip to tiger-free Africa, the title surely points to a military meaning. The abstract jungle in which this tiger hides might make you think of the Pacific islands, where Japanese and American soldiers camouflaged themselves in forests and undergrowth in some of the bitterest battles of the second world war. Behind this pop art version of traditional Japanese printmaking – as behind Andy Warhol’s camouflage paintings – may lie the trauma of 20th-century conflict.

Admitting that possibility would mean opening the floodgates to history in a way this show is determined not to. There is a “Japan Timeline and Yoshida Family Tree” in the catalogue, but the timeline just gives the traditional periodisation of Japan’s epochs from the Edo to today’s Reiwa. Yoshida Hiroshi – the exhibition uses the Japanese custom of family name first – grew up in the Meiji and became an artistic star in the later Taisho era . And so on.

Respecting Japan’s culture is one thing but using it to obscure historical facts is another. In the modern age that this exhibition covers, or rather doesn’t, Japan established a powerful empire under a quasi-fascist military regime. It colonised Korea in 1910, invaded Manchuria in 1931, and ruled these and other territories harshly, finally attacking Pearl Harbor in 1941 and starting a war with the US that ended in the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Out of these ruins was born the success story of today’s democratic Japan.

I’m not raising all this to make trouble. It’s just that history would bring this fairly dull show to life. You are expected to appreciate the art in such closed terms your brain starts wandering – and asking uneasy questions. In fact, the Yoshida family built their success on international openness. Visiting Europe and the US as a young man, Yoshida Hiroshi found out how much westerners, including Monet, Van Gogh and Whistler, loved the Japanese art of observational realism called Ukiyo-e.

Yoshida in turn took on their discoveries, even their settings. His 1925 view, Canal in Venice, turns an Ukiyo-e eye on the dreamy Italian tourist city. Starting in 17th century Edo - today’s Tokyo - artists developed this style, most famously in woodblock prints, to record everyday life in the city’s pleasure quarter. Yoshida looks at Venice as if it was old Edo. Instead of focusing, like Monet, on light and colour, he is fascinated by the tourists, comically depicting sightseers crowding an overloaded gondola. He does the same in Egypt, giving as much attention to graphically sharp Bedouin as to the Sphinx. I found myself thinking of Tintin – whose creator Hergé was another western artist influenced by Japanese prints.

These are refined pleasures, mixing the style of Hiroshige and Hokusai with the impressionists they had influenced. By the 1930s, Yoshida Hiroshi is more purely traditionalist. Instead of cities and foreigners, he depicts parks and temples. In 1940, he portrays people in kimonos visiting the Ninnaji Temple in north-west Kyoto, an ancient site associated with Japan’s emperors: other prints from the same years depict a bamboo forest and an ancient bridge through cherry blossom.

The spiritual conservatism is obvious. Surely these assertions of Japanese national and cultural identity, so much less alive than Yoshida Hiroshi’s earlier views of the US’s Yellowstone or Grand Canyon, are adapted to the extreme ideology of the military regime then leading Japan towards destruction.

In Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel An Artist of the Floating World, a traditionalist artist is haunted by his possible collaboration with Japan’s fascist era. The comparison is no doubt unfair, but the realities of dictatorship, nationalism and war are passed over so completely here it makes you think there’s something to hide. The exhibition fails to include Hiroshi’s views of China and Korea under Japanese rule, charming images that reveal nothing of the violent truth. The catalogue tersely mentions his 1937 series of “12 prints on Korea and Manchuria”, which are not exhibited. Clearly these were propaganda for Japanese imperialism.

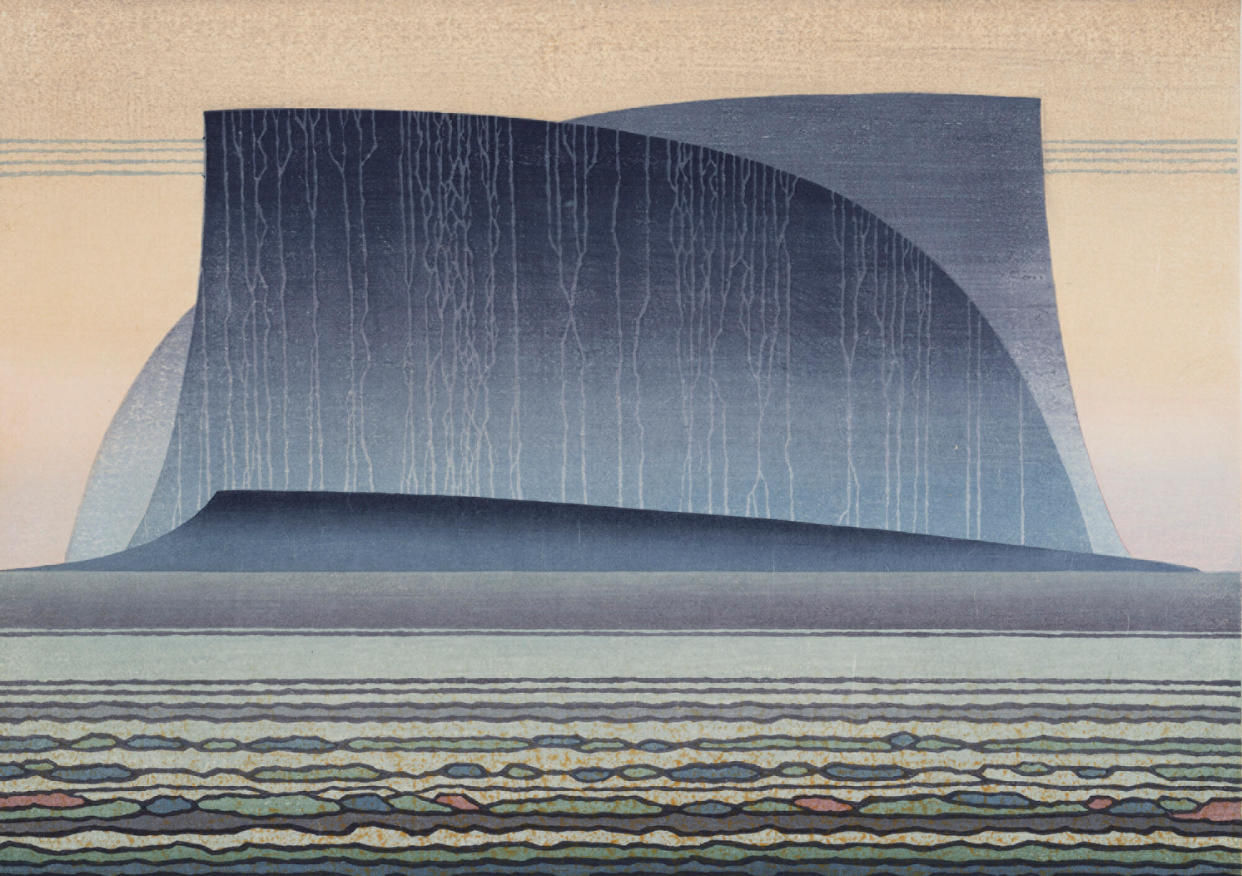

Exploring this would have helped us to understand and appreciate Yoshida. As it is, the catalogue mentions that his son, Tōshi, made traditional prints in the 1940s “but with references to the impact of war”, yet we don’t see these either. Instead we leap to 1951, when Yoshida Tōshi is making abstract prints influenced by US modern art. In the work of his brother Hodaka, too, there are Jackson Pollock swirls everywhere. Paradoxically, these attempts at abstract expressionist printmaking have dated much less well than their father’s work. They surely reflect the cultural dilemma of post-1945 Japan as it sought a new identity. Again, a broader context would help.

In the 1960s, it all comes alive as Japan embraces pop culture. By 1971, Yoshida Tōshi is in Santa Fe, New Mexico, observing a crowd of hippies, tourists and Native Americans with a wit and irony that goes right back through his father to Hokusai. Woodblock prints helped to invent modern art and still have an amazing ability to capture modern life.

In a 1995 print here by Yoshida Chizuko, we see Tokyo’s skyscrapers vanishing into a rainy mist, saturated in blue and rose ink. Venerable craft meets raw metropolis in a vision of reality that breaks through this show’s aesthetic prison.

• At Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, from 19 June until 3 November

Yahoo News

Yahoo News