Young people are campaigning for political change worldwide - but their voices are too often ignored

Young people have taken part in remarkable political mobilisation in the last year. They have participated in global climate change strikes and demonstrations and protests against ruling elites, corruption and inequality in countries such as Algeria, Sudan, Tunisia, Iraq and Libya.

However, my research shows that they can be excluded from decision-making and peacebuilding processes. In particular, young people frequently think that their messages are devalued or ignored.

Young people are often perceived as vulnerable and in need of protection. Yet they can be simultaneously viewed as dangerous, violent and uncontrollable. These views have long dominated attitudes towards youth. Moreover, popular beliefs about young people’s lack of experience and political apathy has meant that many people are ignorant about their contribution to political debate. This has also led to a failure by political leaders to acknowledge young people’s potential to bring about political change.

A flexible understanding of what counts as “youth” means that a person can also be the subject of these attitudes for a surprisingly long time. The definition of youth revolves around age, social and cultural roles or psychological factors. While the United Nations defines youth as individuals aged between 15 and 24, this range varies elsewhere.

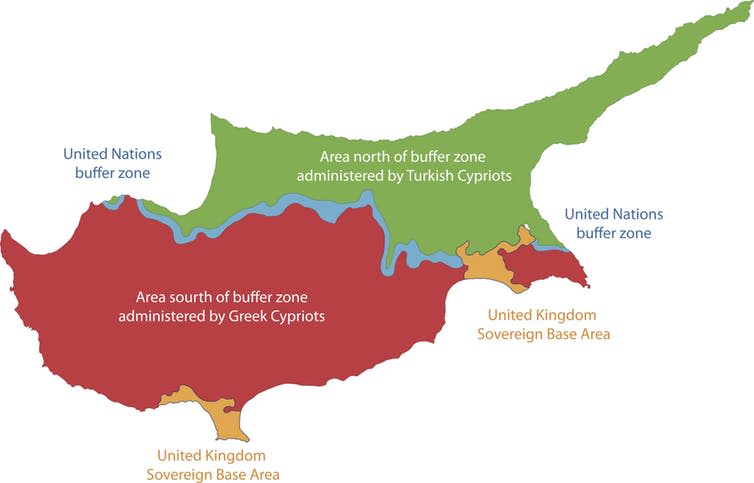

It rises, for instance, to as high as 35 in Cyprus, according to the National Youth Strategy of Cyprus. A 40-year-old unemployed and unmarried west African man may still be considered a “youthman”.

Excluded voices

During my fieldwork in Cyprus, I observed what is known as “adult territoriality”, in which the politics is mainly dominated by older men, and they do not allow young people to take part in any type of governmental body. As one young Cypriot told me, “political parties are hesitant to encourage youth candidates in politics and they don’t have any intention to open the doors to youth either”. This prevents young people from being included in politics, decision-making or peacebuilding.

“It might be because of the Mediterranean culture, but elders do not listen to you until your hairs turn grey,” commented a 28-year-old Turkish Cypriot. “It is deeply embedded in the Cyprus culture that if you are a young person, you [have] no experience to be listened to,” said a 27-year-old Greek Cypriot.

Cyprus is not alone in this regard. Youth-led demonstrations often receive criticism, such as calls for youth climate activist Greta Thunberg to “shut up and go back to school”. And sometimes, young activists are more directly sidelined: Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate was cropped out of a photograph by Associated Press after a press conference at the 2020 World Economic Forum at Davos. The marginalisation of youth activists of colour has also been a persistent trend.

Agents of change

In recent years, the UN Security Council’s (UNSC) resolutions, 2250 (2015) and 2419 (2018), on “youth, peace and security” have marked an attempt to change these attitudes. They recognise the important and positive roles that young people often play. UNSC resolution 2250 identified five pillars – participation, protection, prevention, partnership and disengagement and reintegration – to enable youth participation, especially in peace processes.

Yet there is still work to be done to effectively incorporate youth voices. Young people have the potential to positively contribute to their societies – not just for peace and security, but also for sustainable development – if they are recognised as political actors.

In the case of Cyprus, the UN Secretary General consistently called upon the Greek and Turkish Cypriot community leaders to engage women and youth in the peace processes. This could be either by strengthening the role of women’s organisations and youth participation in the peace process, or by ensuring a meaningful role for them in peace efforts. However, both Greek and Turkish Cypriot community leaders remain reluctant to include the wider public.

Most Cypriot young people are used to living in a divided country. However, some wish to see the division end and seek to contribute meaningfully to dialogue and cooperation between the two sides.

In my research, I sought to understand these young people’s perspectives on everyday peace. When I asked my participants what peace means to them, most of them emphasised the need for peace at the societal level rather than a government-led solution – with a particular focus on daily practicalities. These include things like travelling to either side without any checkpoints, or using their mobile phones without extra fees.

Cypriot youth may not be as politically active for peace as they were in the run-up to the 2004 referendum on the Annan Plan, or the period in 2011 when there was a movement to occupy the buffer zone between the north and south, and when young people were involved in demonstrations for peace. But the island’s youth still believe that they have a responsibility to find a peaceful solution to the “Cyprus problem”.

Although countries are hesitant to include youth in politics, young people find alternative ways to cope with marginalisation and amplify their voices. This is apparent in the youth-led protests around the world. Young people are demanding to be leaders today, rather wait their turn in an elusive future.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Cihan Dizdaroğlu's project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 796053.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News