The 1833 Treaty of Chicago forced Native Americans off their land, but legal disputes continued for years

In June 1905, the Tribune recalled that some 70 years earlier, diplomacy had been a thriving industry on Lake Michigan’s shore, far removed from its accustomed focal point in the nation’s capital.

“In the days of Chicago’s youth, treaties were negotiated here. Representatives of the United States and of the Potawatomi and other tribes held solemn councils here and entered into agreements by which the Indians gave up much and got little.”

Collectively, those treaties stripped the Indians of their tribal lands. They proceeded apace with the westward movement of European farmers and ranchers. Indians not only lost their hunting grounds, they became foreigners in someone else’s country. Until 1924, Indians weren’t American citizens.

But in 1914, one group fought back. Weaponizing the white man’s legal chicanery, the Pokagon Indians sued the city of Chicago, claiming a valuable piece of the metropolis was rightfully theirs. They wanted land that is now home to parts of the Gold Coast, Lincoln Park and Lake Shore Drive returned to them.

The Pokagon Band was a subdivision of the Potawatomi tribe that historically inhabited villages in stretches of land that became Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin. But in 1833, progress, as Europeans defined it, caught up with the Potawatomi.

On March 5, 1833, Thomas Jefferson Vance Owen, the government’s Indian agent in Chicago, sent a letter to Elbert Herring, commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington. Having consulted with “the most intelligent and influential” Indian chiefs, Owen said he didn’t think they would surrender their tribal lands and move West of the Mississippi River, as Congress had ordered three years earlier in the Indian Removal Act.

The act envisioned a division of the United States into separate territories for Native Americans and whites. But the Indians were suspicious of exchanging familiar hunting grounds for unseen frontier land.

The feds felt pressured to get a deal done. The opening of the Erie Canal made it easier to get to Chicago from the East Coast. The number of would-be farmers arriving here was increasing. Should they bump heads with Indians, bloodshed seemed certain. The two ways of life were incompatible. Agriculturalists need defined plots to seed. Nomads need wide-open land to hunt.

That scary scenario was reinforced when Owen was instructed to convene a meeting of whites and Native Americans to hammer out an agreement. Negotiations ran through late September. Tribal members and other sorts descended on Chicago. According to a Tribune remembrance of the event from 1942, “a large open arbor” was put together north of the Chicago River and east of State Street for a council house “By September about 6,000 Indians had come in for the doings, as well as claimants, tourists, travelers, horse dealers and stealers, and rascals and rogues of all kinds,” the Tribune wrote.

Under terms of the treaty, land along Lake Michigan were ceded to the United States, and federal appropriations of more than $1 million in grants for the Native Americans displaced by the treaty were approved two years later.

On Aug. 18, 1835, in a final act of defiance before the deadline for them to be gone, hundreds of Indians wielded tomahawks and held a War Dance in Chicago.

“The Indians realized that this was their last parade on their native soil, so the performance was a sort of funeral ceremony for old associations and memories for them,” the Tribune wrote in 1910, just ahead of the dance’s 75th anniversary.

White settlers saw it as the template for a massacre. John D. Caton, an eyewitness, left a bloodcurdling account:

“Their tomahawks and clubs were thrown and brandished about in every direction with most terrible ferocity and with a force and energy which could only result from the highest excitement, and at every step and every gesture, they uttered frightful calls in every imaginable key and note — generally in the highest and shrillest possible.”

Legend and lore has it that the Pokagon sat at a distance from other Potawatomi. They didn’t want to be called upon to sign the Treaty of Chicago. They could scarcely realize it at the time, but a provision of the treaty became the fulcrum by which they hoped to pry Chicago neighborhoods out of the white man’s hands.

The Pokagon took their name from an early Wkema, or leader, Leopold Pokagon. He negotiated an exception to the Treaty of Chicago that allowed his band to remain on land in Michigan when the other Potawatomi were exiled. Reportedly he had the advantage of being a teetotaler during the negotiation over the treaty even as booze flowed freely, thanks to speculators determined to pocket the cash the government was offering the Indians.

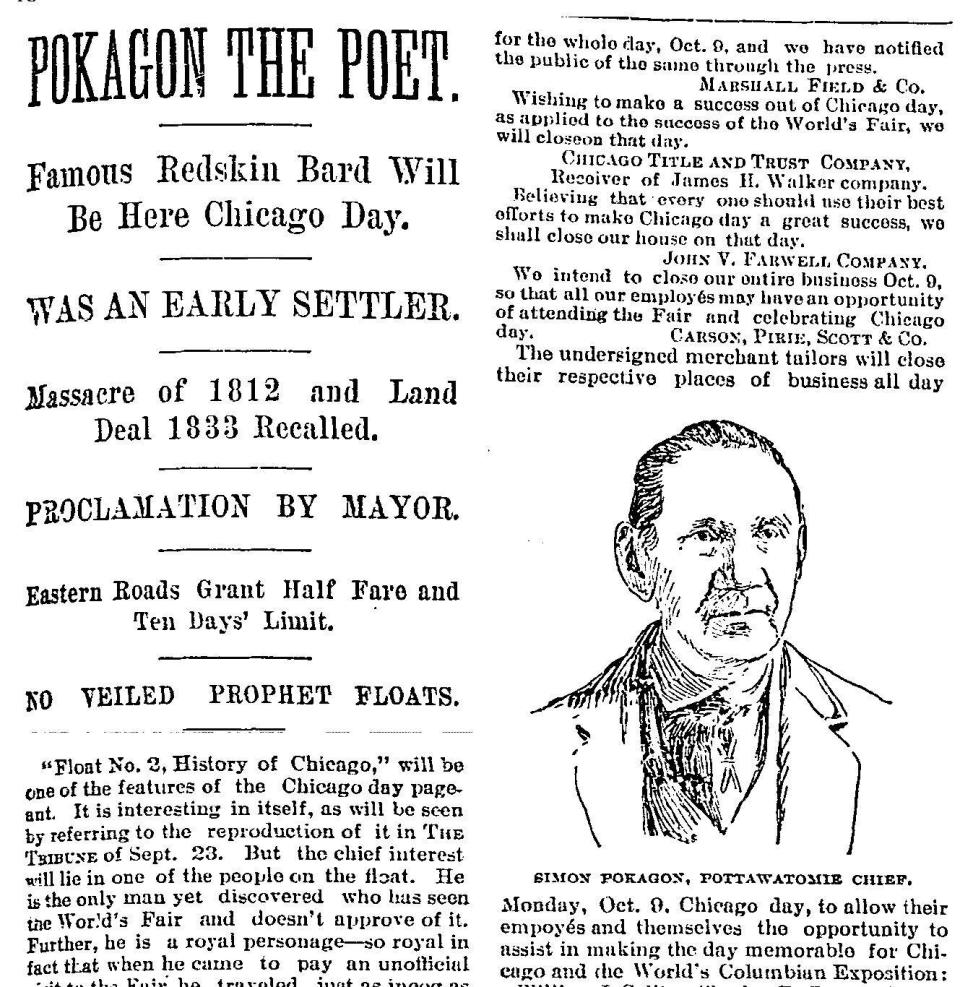

Leopold was succeeded by his son, Simon Pokagon. A charmer, he was admired in high-society salons while campaigning to get the land under Chicago’s mansions returned to the Pokagon.

He turned the trick with literary accomplishments. He was known as the “Red Man’s Longfellow.” He wrote poetic laments for the passing of traditional Indian culture. One was an ode to the birch tree for donating its bark for his people to build canoes and tipis.

His “Red Man’s Rebuke” was a sharp-tongued put-down of the World’s Fair” belatedly marking the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage.

“In behalf of my people, the American Indians, I hereby declare to you, the pale-faced race that has usurped our lands and homes, that we have no spirit to celebrate with you the great Columbian Fair now being held in this Chicago city, the wonder of the world.”

Nonetheless, he spoke to an enormous audience at the 1893 Fair. Until his death in 1899, he insisted that Indians were due the return of their lands.

The next activist generation took the war of words to the courts, and the Indians’ struggle became national news.

“If the Chicago claim is established, they will squat on all the lake front from the Indiana line to Grand Haven, Michigan,” the Los Angeles Times reported in 1901.

At the time of the Chicago Treaty, the shoreline was just east of Michigan Avenue. Subsequently it moved further east, beginning with the dumping of remains of buildings destroyed in the Chicago Fire of 1871. Whole new neighborhoods emerged.

So how could their forefathers have conceded land that didn’t exist in 1833, as the government contended? The Pokagon put the issue to the U.S. Court of Claims and asked it of a congressional Committee. Both dodged it.

In 1901, there was a rumor of an invasion of Chicago, possibly floated by the Indians as a bargaining chip. The superintendent of police dismissed it as “overindulgence in ‘fire water’ by the chiefs of the tribe,” the Tribune reported.

The tribe tried selling their claim, an investor said he had bought it, and threatened invasions continued until a prominent Chicago attorney took the Indians’ case.

“One day in the year 1913 seven American Indians were ushered into J.G.’s office,” wrote the grandson of Jacob Grossberg, in his biography of the prominent Chicago attorney. “In essence, the Indians claimed that land along the shore of Lake Michigan upon which built expensive residences, a steel mill, parks and tracks and terminals of the Illinois Central Railroad belonged to them.”

The following year Grossberg filed a lawsuit that would end in strikingly similar fashion to Simon Pokagon’s forecast in his book, “Queen of the Woods.” The protagonist prays that his late wife will save him from an impending death, when her spirit appears.

“The maiden passed her hand above his head; he began to grow small, streams of water began to run out of his mouth, and soon he was a small mass upon the ground, his clothing turned to withered leaves.”

In courtrooms, the Indians’ dream became a nightmare. The city of Chicago argued that the Indians had “abandoned their claim,” forfeited it by not asserting it earlier. In 1917, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the trial court’s decision, saying: “The claim set up in this cause is without merit.”

Subsequently, the court cited the Chicago case as precedent when turning down other tribes’ requests for compensation for land they lost.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News