192 people in B.C. died due to toxic drugs in March: coroner

The B.C. Coroners Service is reporting at least 192 deaths related to toxic drugs in March, bringing the total lives lost in the first three months of the year to at least 572.

More than 14,400 people in the province have now lost their lives to toxic drugs since a public health emergency was first declared in April 2016.

"These were people with hopes, dreams and stories cut tragically short by a crisis that continues to challenge us deeply," Mental Health and Addictions Minister Jennifer Whiteside said in a statement.

"We remember not only those we've lost, but also their families and friends left to grieve."

The numbers for March equate to 6.2 deaths per day. They mark an 11 per cent decrease from March 2023, when 215 people or almost seven each day died from toxic drugs.

Unregulated drug toxicity remains the leading cause of death among British Columbians aged between 10 and 59, the coroner says — more than murders, suicides, accidents and natural causes combined.

The service says that so far in 2024, 70 per cent of toxic drug deaths have been people between the ages of 30 and 59. Three-quarters of those lost have been men, but the coroner warns that the number of female deaths is climbing.

So far this year, 84 per cent of toxic drug deaths have happened indoors: 47 per cent in private homes, and 37 per cent inside places like supportive housing, SROs, shelters and hostels.

Vancouver, Surrey and Nanaimo have the highest numbers of toxic drug deaths in 2024.

Last month, the province announced big changes to its drug decriminalization program, which was introduced in January 2023 as a three-year pilot.

The program allowed adult drug users in B.C. to carry up to 2.5 grams of opioids, cocaine, methamphetamine and ecstasy for personal use without facing criminal charges, with the goal of reducing stigma and helping drug users access support.

The provincial government has now recriminalized the use of drugs in public places including hospitals, on transit and in parks, a request Health Canada approved on Tuesday.

"Our communities are facing big challenges. People are dying from deadly street drugs and we see the issues with public use and disorder on our streets," Minister of Public Safety and Solicitor General Mike Farnworth said in a statement on April 26.

Stigma 'can be a killer'

B.C. United, the province's Official Opposition, has criticized the pilot's stated goal of destigmatizing drug use in recent weeks, arguing that using criminalized substances should not be normalized in B.C. or anywhere.

However some working in treatment and recovery services in B.C. say stigma "can be a killer."

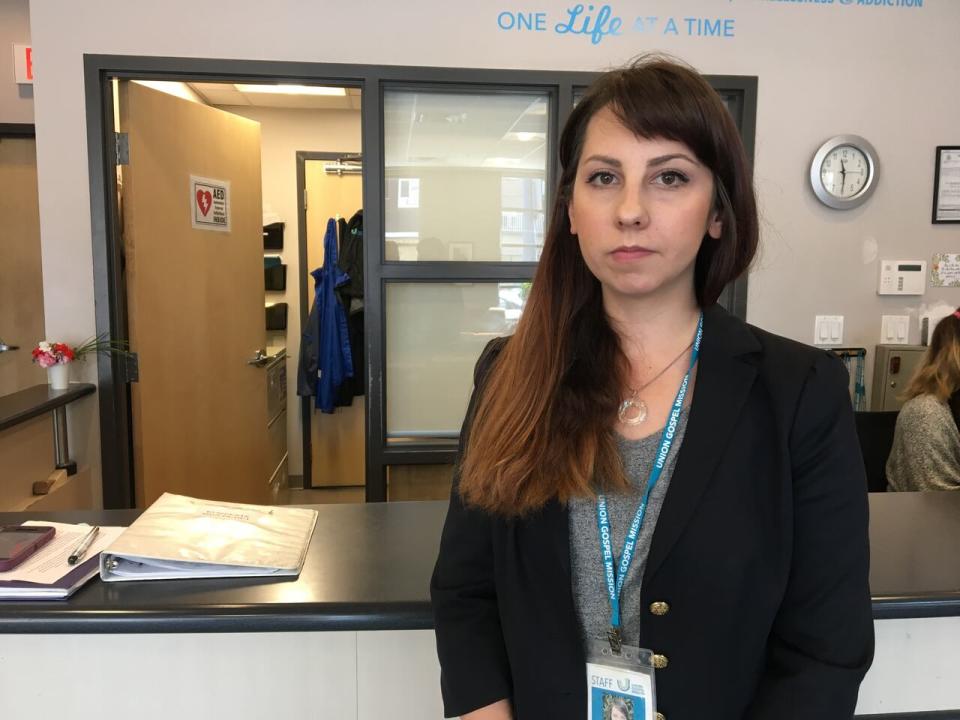

"It's fear — or fear of judgment that holds them back from seeking recovery," Nicole Mucci, communications manager with Union Gospel Mission, told Michelle Eliot, host of CBC's BC Today, on Tuesday.

"Forcing shame into a conversation already laden with shame is probably not the most strategic or safe approach."

Nicole Mucci from the Union Gospel Mission, pictured in 2018, says stigma "can be a killer" and it can deter people from asking for help with their addiction or substance use. (Denis Dossmann/CBC)

Fear of losing housing or being unable to support a partner, children or relatives also prevents people from seeking help, according to Chatman Shaw, a board member for Trinity House, a men's recovery facility in Prince Rupert, B.C.

"The politicians aren't looking at the underlying issues for the people who are addicted," Shaw told BC Today on Tuesday. "People aren't seeking help because they don't have the means of surviving."

"If you lose your apartment in a place like Rupert, you are more or less destined to be homeless."

Shaw, who also works as a longshoreman, says many people struggling with substance use can also be subjected to abstinence-based return-to-work agreements with rigorous testing programs to check their sobriety.

"It really alienates people from the rest of the workforce," he said. "The shame, the guilt, you're remorseful, and your family suffers as a result … [it] could be a means to push you off the edge.

"We need to be looking at ways and means of helping people survive."

Yahoo News

Yahoo News