50 Years on – how Apollo 13's near disastrous mission is relevant today

Eighteen months ago, I was combing through the Apollo 11 mission logs, looking at the timelines and events for something unique that we might focus on to celebrate the 50th anniversary of humankind’s first landing on the moon. Last year, that idea became the BBC World Service podcast 13 Minutes to the Moon.

As the series drew to a close, it became clear that there was unfinished business. Some of the flight controllers who had been present for the Apollo 11 landing had also worked on another, arguably more dramatic, endeavour – the ill-fated flight of Apollo 13.

That mission was crippled by an explosion while en route to the moon and nearly 200,000 miles from Earth. The story was popularised in 1995 in a Hollywood film starring Tom Hanks, but I knew that there was much more behind the narrative than the movie had managed to tell. So for the new series of the podcast I wanted to get under the skin of the thing and focus not just on the crew who flew the mission, but also on those who saved it – the incredible team of flight controllers who worked round the clock in shifts for 87 hours.

We were after more than the story, gripping though it is. I wanted to understand what lessons we all might learn from what became arguably Nasa’s finest achievement: the recovery from catastrophe in deep space and the rescue of a crew from what looked like certain death. How do you lead a team through that? How do you keep yourselves going in the face of something so hopeless? It felt to me like there should be something all of us might learn.

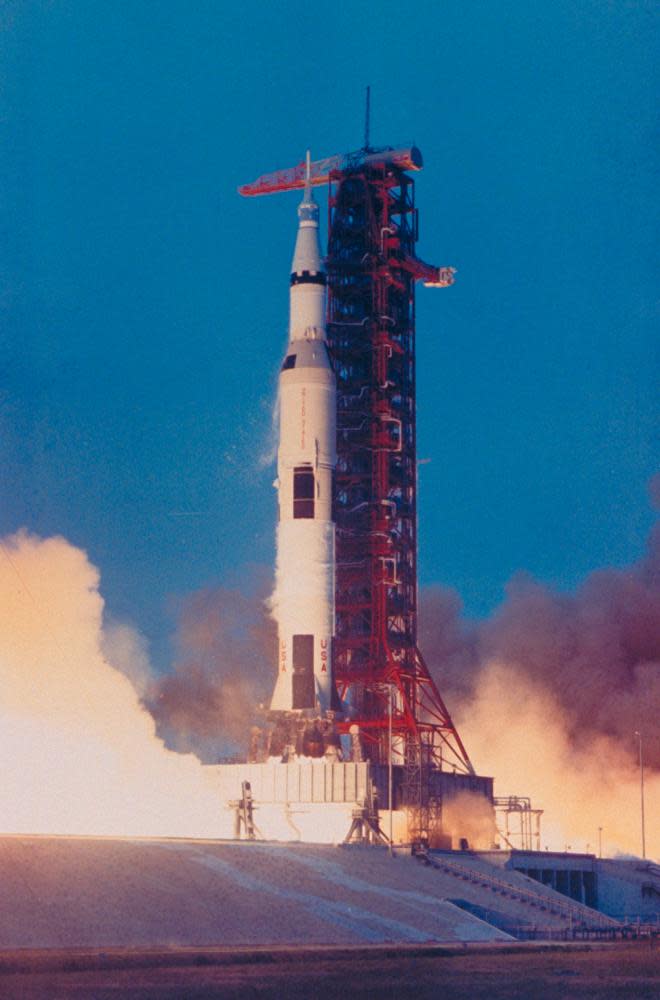

Apollo 13 was the United States’ third mission to land humans on the moon. Launched on 11 April 1970, it followed less than a year after Neil Armstrong’s successful first lunar landing and famous small step. Commander Jim Lovell, a former US navy test pilot and spaceflight veteran, led a crew of two rookie astronauts, Jack Swigert and Fred Haise. Things had gone awry even before launch. Swigert was a late inclusion in the crew, having been swapped in at the last moment to replace his colleague Ken Mattingly who had been exposed to a case of German measles. But this drama in the buildup to the mission drew only moderate interest from the media.

To the American public, sending people to the moon, a feat that had existed only at the limits of their imagination just 12 months earlier, had now taken on the air of something almost routine. There was much less press hoopla about the launch itself and television networks across America declined the opportunity to interrupt their schedules and include live inserts of Apollo 13’s early inflight broadcasts. The view of the editorial teams back on Earth was clear: astronauts had landed on the moon not once but twice already and, with much of the novelty gone, the Apollo 13 mission deserved little attention, or so they thought.

Fifty-six hours in, with the crew nearly 200,000 miles from Earth, an explosion in one of Apollo 13’s two oxygen tanks left the command module Odyssey fatally damaged. Coasting in space, with alarms flashing all around them, bleeding oxygen and losing electrical power, Lovell, Swigert and Haise were suddenly in deep trouble.

The lunar landing was called off and over the next four days, the crew and mission control would find themselves fending off deadly threats over and over again. They would solve problems one day, only to discover a host of new complications that might kill the crew the next. But they kept working together, across hundreds of thousands of miles of empty space, with everything against them, until they got the crew all the way back.

On 17 April 1970, with the world watching, Apollo 13 reached Earth again. The capsule, surrounded by an inferno created by the heat of re-entry into the atmosphere, became impossible to contact by radio. At mission control, they watched and waited in silence.

We tend to mythologise these stories of outrageous survival to the extent that it becomes difficult to tease fact apart from fiction. This is doubly true of Apollo 13. The popular retelling goes something like this: Apollo 13 was rescued by an elite team led by flight director, Gene Kranz, for whom failure was “not an option”. The rescue was executed calmly and deftly without any doubts that it would succeed.

But you only have to listen to the opening hours of the mission control recordings and the space-to-ground radio transmissions to know that was not the case. After the rupture of the oxygen tank, both the crew and their flight controllers struggled to make sense of what was happening.

That the mission control team was caught flat-footed in the opening phase of the accident is strangely reassuring. Nobody, not even the exhaustively drilled Nasa flight controllers, is able to glide swan-like through chaos like that. Initially there was no structure. There were misdiagnoses and mistakes. The vehicle had failed so totally that it fleetingly crossed the mind of at least one flight controller that he should simply pack up and go home.

Exemplary leadership is what got them through that first hour. Kranz kept his team and the vehicle together masterfully, buying time enough to start solving the problem. When reviewing the response to sudden crises, we often overlook that chaotic period, simply because it has little real structure and doesn’t appear to move things forward. But preventing a team from disintegrating in the face of an apparently overwhelming challenge is a feat in itself. The average age of the flight control team was 27; some were freshly graduated from university. During routine mission operations you would never guess that; their statements are so clear and confident, their knowledge so deep. But immediately after the accident there are times when, listening to the mission audio loop, you hear a hint of fearful youth.

Nasa had learned to be wary – they knew that plans hatched in the heat of the moment often harbour flaws

After a torrid hour of failed troubleshooting, a new shift of flight controllers arrived, as well as a new flight director, waiting to take their turn. They were at this point still in the thick of the fight and the temptation for Kranz to keep going and refuse to relinquish control must have been enormous. Nevertheless he passed the baton to the incoming team, recognising that fresh eyes and minds were what was needed. This is the true spirit of teamwork – the ability to know when your part is done, when someone new can bring something better than you can.

That ability to relinquish control and delegate authority didn’t stop there. The Apollo missions were complex endeavours. Nobody could be across it all and Nasa knew that in mission control it had a team of people who, as a whole, were far greater than the sum of their individual parts.

In approaching this crisis, their delegation of authority and deference to expertise is almost total. In the face of high-stakes scenarios, it is tempting to wrest control from more junior colleagues. But in 1970 the approach of mission control was quite different. They empowered their most junior team members, giving them total ownership of their specialist stations. They would interrogate their recommendations but not second-guess them. It is a lesson that industry and wider society has largely failed to heed.

The other aspect of the Apollo 13 mission that I found fascinating during our interviews with the team was the depth of Nasa’s preparation. I had always imagined Apollo 13 to be a feat of wall-to-wall improvisation. After all, the rupture of the oxygen tank had torn the heart out of the command module, leaving it dead, forcing the astronauts to use the lunar module as a lifeboat and means of propulsion.

But what surprised me was how little of the response to the accident demanded improvised solutions. Nasa had learned to be wary of creativity and inventiveness in the heat of the moment. That doesn’t mean it refused to improvise, nor that it wasn’t capable of doing it well – only that it knew plans hatched in the heat of battle often harbour hidden flaws.

Incredibly, Nasa had already rehearsed many of the contingency and fallback plans required to rescue Apollo 13. In earlier missions, it had experimented with using the lunar module’s engines to drive both it and the command module. It had a checklist ready to manage the sudden powering down of the command module that was required to save dwindling battery power. Nasa even had a procedure for flying the spacecraft without their primary navigation and guidance computer. And then, when finally it had no choice but to improvise, it did it with same obsession and attention to detail it brought to everything else.

Finally, we should turn to the things we think we know about the mission through retellings in popular culture. The best quotes are often misquotes. For example nobody ever said: “Houston, we have a problem.” The precise words were: “Houston, we’ve had a problem.” That is just a glitch in tense.

More significant is the mission’s other catchphrase – “Failure is not an option” – which we have taken to characterise Nasa as the sort of steel-willed organisation that steadfastly refuses to entertain the possibility of failure. But in truth nobody uttered those words during the mission. The quote itself derives from a line of script in the 1995 movie and Kranz then borrowed it as the title for his autobiography, published in 2000.

And while the flight controllers enjoyed regurgitating that particular strand of mythology to us, it was clear that the possibility of failure remained very real throughout the mission. Fifty years later, several of the flight controllers were still moved to tears when describing the moment when Apollo 13 finally reappeared after the communications blackout.

Despite their protestations, it became obvious that they all must have known how perilous the scenario was. But, importantly, what they didn’t do was devote any time to contemplating disaster. As flight director Glynn Lunney, who relieved Kranz’s first shift told me: “If you spend your time thinking about the crew dying, you’re only going to make that eventuality more likely.”

• The second series of 13 Minutes to the Moon starts on the BBC World Service at 11.30am on Wednesday 11 March. It will be available on BBC Sounds from Monday 9 March

Yahoo News

Yahoo News