Eastern Europe Is Richer Than Ever — And More Divided

(Bloomberg) -- Zakovce in eastern Slovakia is the definition of a backwater. Yet as part of the European Union, its sidewalks are new, its sewage system works and nearby factories churning out auto parts and appliances helped more than halve the unemployment rate in the region.

Most Read from Bloomberg

NYC Police Break Up Columbia Protest and Clashes Erupt at UCLA

Amazon Posts Strongest Cloud Sales Growth in a Year on AI Demand

Lilly Soars as Forecast Boost Shows Weight-Loss Drugs’ Power

The village, though, also encapsulates how 20 years of EU membership have transformed Eastern Europe from an economic success into a political challenge for the bloc as nationalist parties exploit lingering income disparities.

Zakovce is home to Marian Kuffa, a Roman Catholic priest whose conservative views on abortion, same-sex couples and gender have won him nationwide popularity and as many as 1 million views on social media for his sermons. He boasts he can get 100,000 to 200,000 votes for any politician who needs them as long as that leader defends Christian values.

“Communism fell because it forbid everything, and liberalism will fall because it allows everything,” Kuffa said in an interview this month at a small library in a compound he runs for ex-convicts, homeless and alcoholics.

It would be easy to dismiss Kuffa as a fringe figure, but his influence on Slovak politics lays bare the fragility of the marriage between the EU and the former Eastern Bloc. While most citizens still back the EU, populist voices have sowed discontent that’s now entrenched after being turbocharged by the 2015 refugee crisis, coronavirus pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

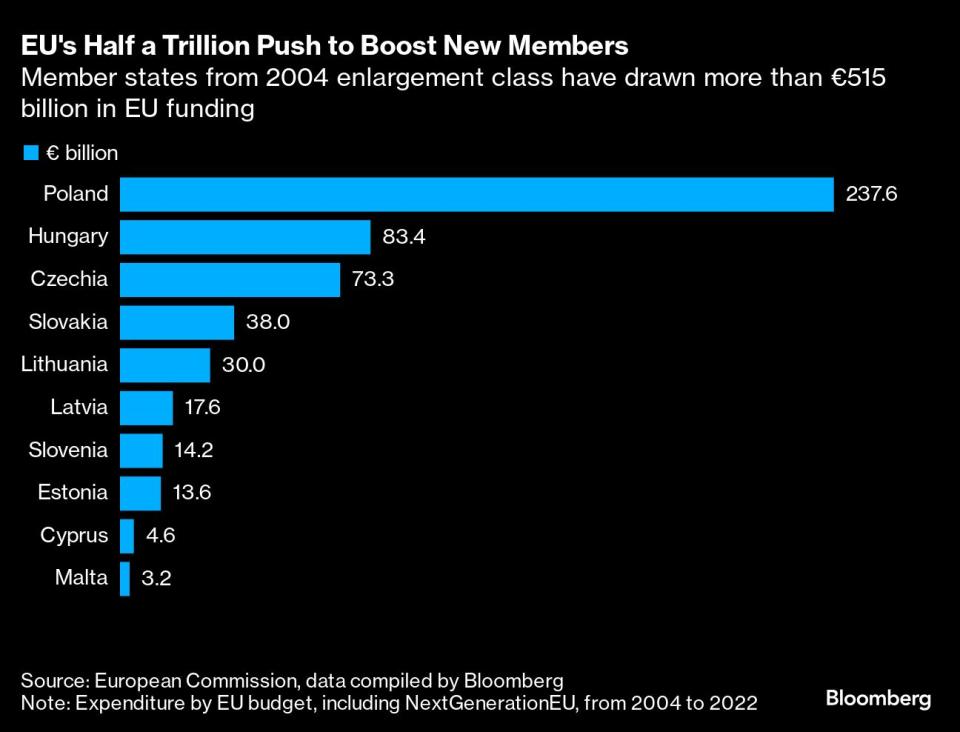

The EU has poured about 515 billion euros ($548 billion) into the eight former communist nations, as well as Malta and Cyprus, since they became members on May 1, 2004, according to Bloomberg calculations from European Commission expenditure data available through 2022.

Yet, taken together, more people back political groups opposed to the EU’s stance on everything from migration and LGBTQ+ and gender rights to green policies aimed at tackling climate change than ever before.

Read More:Poland’s $300 Billion Windfall Hides Flaws in EU Expansion EastEU Bankrolled Eastern Rebellion That Threatens to Tear It ApartEurope’s Battle With Its Eastern Rebels Leaves Lasting DamageThe Far Right Is Advancing in a Vulnerable Europe Again“I expected that eastern countries would have a more significant role in the EU after 20 years, that they would be able to influence and shape decisions at the European level more, that the political elites in our countries would have a greater sense of co-ownership of the EU, ” said Milan Nic, a senior fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations in Berlin. “That did not happen.”

In Hungary, the EU is still withholding €20 billion of funding because of concern about corruption and Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s erosion of democracy.

Billboards in Budapest ahead of June’s European Parliament elections portray opposition figures as puppets of Brussels, while pro-EU groups implore people to choose Europe. Orban recently described planned legislation on migration as “another nail in the coffin” of the EU.

In Poland, which has absorbed more EU funds per capita on a net basis than anywhere else, the new government of Donald Tusk is trying to unpick eight years of rule by the nationalist Law & Justice Party. That leadership, like Hungary’s, demonized the EU for foisting its “liberal values” on countries that didn’t want them, even as its money helped increase gross domestic product by more than 50% over its time in power.

Sandwiched between the two, Slovakia stands out because it overcame the biggest hurdles at the time to get into the EU and raced ahead to join the euro. From the late 1990s, the nation of 5.4 million took painstaking economic and political reforms to catch up with its neighbors.

Since then, foreign car makers such as Volkswagen AG and Kia Corp helped fuel its growth and reunification with democratic Europe. Slovakia’s economic growth has averaged 3.3% over the past two decades. Yet here, too, the prevailing wind is against the European mainstream thanks to influences like Kuffa.

Last year, former Premier Robert Fico returned to power as the voice of opposition to Brussels. His Russia-friendly stance puts the country at odds with partners and threatens to break up Europe’s unity in helping Ukraine. He also openly pokes fun at issues around gender.

Fico was able to form a majority coalition thanks to the Slovak National Party, which was endorsed by Kuffa. The priest also has claimed his backing helped Fico ally Peter Pellegrini win the presidential election this month.

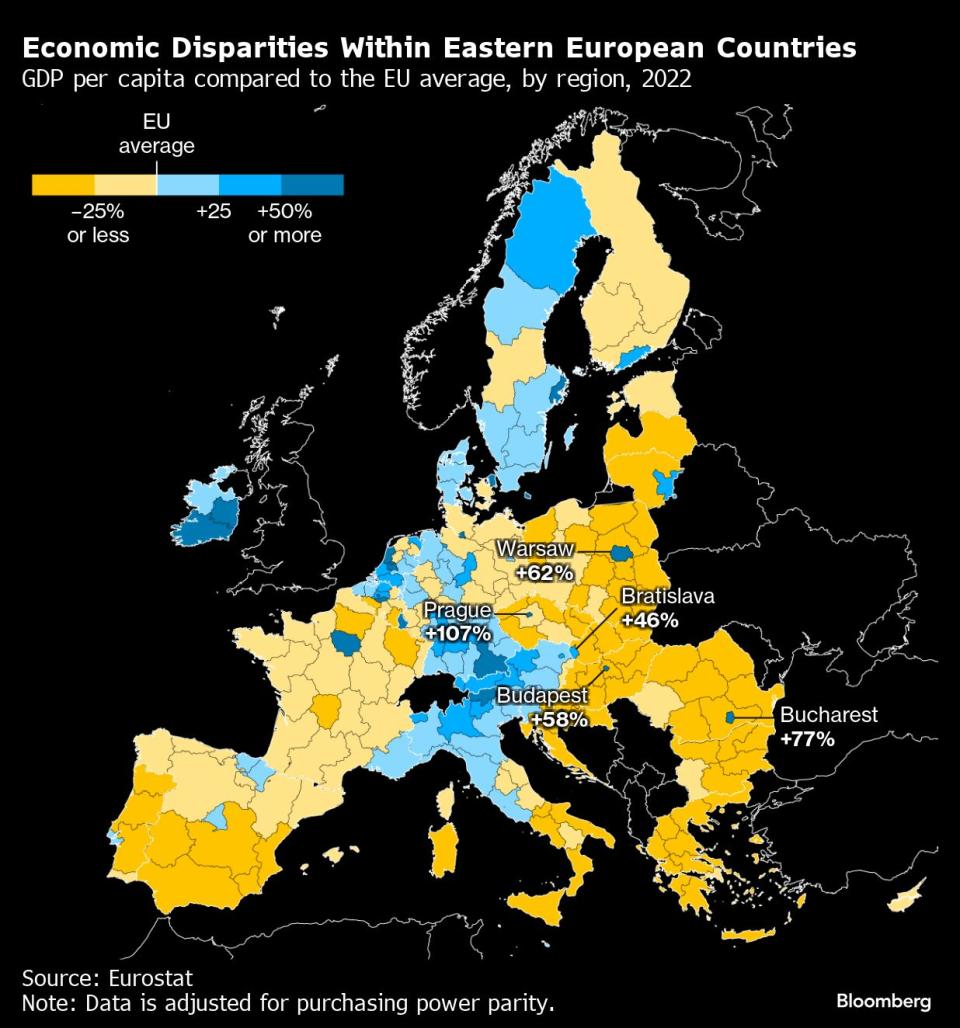

As ever, politics reflects economics. While EU money increased living standards, the division between wealthy, more liberal cities and the conservative countryside widened.

Per-capita GDP in Bratislava, the Slovak capital, in 2022 was 146% of the EU average, according to Eurostat data. In eastern Slovakia, the region that includes Zakovce, it was 52% of the average.

That’s bred resentment, regardless of the improvements in living standards. One pensioner blamed Western Europe for the poor quality of potatoes and for not bringing enough affordable housing or jobs for the younger generations. “Nothing works,” said Helena, 81, declining to be identified by her full name. “Everything was better under communism.”

The problem is that vast swathes of the region are struggling with what the EU has delivered politically, if not economically, said Rastislav Pastierik, 29, in the village of Huncovce next door to Zakovce. For Pastierik, EU membership meant having spent five years working abroad and later getting a good job in an international corporation.

“We’re not yet adjusted for the liberal-democratic train we got on,” he said. “The discussion about advantages of our membership has disappeared.”

Indeed, the list of those advantages is lengthy. On average, the incomes of more than 70 million Eastern Europeans have at least doubled, they live at least three years longer and every household from Vilnius to Prague owns at least one car.

Borders that once separated them are gone. Five out of eight nations have ditched their currencies for the euro and many have at least one dollar billionaire, with the Czech Republic leading the ranks. Buying goods is now a click away and oranges and bananas have turned from luxury foods to staples. Prague, Budapest, Warsaw and Vilnius all have higher per-capita income than the EU average, along with Bratislava.

Lithuania’s central bank governor, Gediminas Simkus, described EU membership as more important than the Marshall Plan that helped rebuild Europe after World War II.

Most funds went to Poland, where they helped transform the country’s infrastructure from railways, road and airports to agriculture. Poland now exports food worth €30 billion a year, compared with €4 billion at the time of its EU entry.

“Joining the EU gave us a major boost in our development,” said Wieslaw Gryn, a farmer in eastern Poland. “My friends and I always laughed that I squeezed everything I could to modernize and expand the farm. It was like an arms race.”

His ability to access EU money helped him convert the land once farmed by horses to a state-of-the-art one where GPS-operated technology and satellite images help him decide which fields need more fertilizers.

Yet farmers are now among the most vocal critics of the EU, particularly Polish ones opposing grain imports from Ukraine. They have taken to the streets this year and blocked border crossings with Ukraine and other neighbors.

It’s not just anger at what they say is the uncontrolled influx of Ukrainian produce, but also against the EU’s Green Deal, which aims to zero out greenhouse gas emissions by the middle of the century.

Back in eastern Slovakia, Pastierik still believes the advantages of EU membership will prevail. The danger is that voices like that of Kuffa can sway public opinion easily, he said. “The problem is that people listen to him,” Pastierik said as he walked around the town with his baby in a stroller on a Sunday afternoon, “and blindly believe what he says.”

Sign up to the Eastern Europe Edition newsletter, delivered every Friday, for insights from our reporters into what's shaping economics and investments from the Baltic Sea to the Balkans.

--With assistance from Natalia Ojewska, Milda Seputyte, Jan Bratanic, Aaron Eglitis, Jorge Valero and Tom Fevrier.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News