Afghanistan Women’s Shelters Are Dwindling Under Taliban Rule

When the Taliban retook power in Afghanistan in 2021, a Taliban member asked Razia’s father for her hand in marriage. Her family, former government workers, felt the marriage was the only way to avoid harassment from the Taliban. When Razia (a pseudonym to protect her safety), who was 18 at the time, refused the marriage, her family beat her so severely that she attempted suicide. The beating continued and eventually, her mother was forced to take her to a local medical clinic.

A few months earlier, a foreign journalist had slipped Razia his number, and told her to call if she needed help. She dialed him from the clinic. “I was so scared to go back home,” Razia says. “My only chance to leave was to call a man I didn’t even know.”

The journalist gave Razia the number for Payvand Seyedali, an education and gender specialist, who had just started The Khadijah Project, an organization that runs some of the last remaining women’s shelters in Afghanistan. Seyedali helped Razia leave her family a few weeks later, and after seeking refuge in one of The Khadijah Project shelters, Razia went on to work with the project, helping more than 60 women and their families to date.

Razia says Afghan women who find the courage to leave their families face an uncertain future—and the threat of domestic abuse is far from the only challenge. “They can’t go to school, to university, or to work. They feel there is no use in being alive and they don’t feel safe,” she says. “I was living in a dark place, I lost all my hope also. But The Khadijah Project gave me a purpose and now I am getting my hope back.”

Nearly three years after the U.S. withdrawal, women in Afghanistan face more challenges than ever. Since retaking power, the Taliban government have broken their earlier promises to give women the right to work and study. They created an all-male government, banned girls from getting a secondary education, imposed strict dress codes, restricted their movement, right to work, and participation in public life, and they have dismantled the few frail gender-based violence support systems that previously existed in the country. UN experts have said the Taliban’s treatment could amount to “gender apartheid,” by implementing a system “of total discrimination, exclusion, and subjugation of women and girls.”

Among many other violations, there have been targeted attempts to silence female journalists; women’s rights protestors have also been beaten and arrested. Many women have fled the country, others are still trying to. But for those without the means to leave, women’s shelters and safe houses are crucial lifelines, providing refuge and a variety of support services including legal advice, education, health care, family mediation, and psychological support.

Protecting, enabling, and empowering Afghan women was one of the ostensible goals of America’s 20-year war in Afghanistan, and countries around the world invested hundreds of millions of dollars in the cause. According to the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), a U.S. watchdog agency, from 2002 to 2020, the U.S. alone spent over $787 million to support women and girls in Afghanistan, including $11 million per year on shelters that supported roughly 2,000 women and girls.

But now, the shelters are struggling to stay afloat as funding from the U.S. and the international community has dried up in the wake of America’s withdrawal. Some shelters have been shuttered or completely dismantled—for example, interviews conducted by the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) in December last year found that all of the country’s 23 specialized women protection centers (shelters sponsored by the previous Afghan government), have now closed, while others now operate on a scaled-down basis.

The American nonprofit Women for Afghan Women (WAW), Afghanistan’s largest network of women’s protection services operating for 20 years, permanently shuttered all of their shelters and family-guidance centers, and their senior staff left the country after the Taliban government returned. WAW co-founder and former board member Masuda Sultan estimates that between 600 and 1,000 women and their children from WAW shelters were left homeless overnight. “Some of them went back home, to their abusers, others are in hiding, or on the streets, or in the park on their own,” Sultan says. “The WAW [response] was, ‘It’s over. we’re not doing shelters anymore.’ There was just no responsibility.” (WAW did not respond to questions sent by ELLE.)

Sultan says that while WAW tried to evacuate some of the women, many were left behind. She is still working to find and support the women through a new humanitarian organization she formed, ABAAD: Afghan Women Forward, which is run by 30 local volunteers. “We have a list of 100 women right now that desperately need help,” Sultan says. Three women have been killed since their shelters closed; another was kidnapped and disappeared, Sultan says. “So far, we are supporting 60 women and their children in three provinces, but the biggest hurdle is funding. ABAAD is running on individual donations, and it’s just not sustainable,” she explains. “We’re taking it one step at a time. It’s just triage right now and my biggest fear is, how much capacity do the few shelters left open have?”

The few shelters that remain today rely on funding from a handful of foreign philanthropists, individuals, and small foundations, but it’s not enough to cope with increased demand of women and girls who desperately need their support.

In addition to the lack of funding, threats of violence have also forced some shelters to close their doors. Those that remain open do so knowing they could be closed at any moment. In September 2021, Taliban gunmen entered a women’s shelter in Kabul, interrogated staff and residents, and forced the head of the shelter to sign a letter promising not to allow the residents to leave without Taliban permission, according to a U.S. state department report. The Taliban told the shelter operator that married shelter residents would have to return to their abusers, while unmarried shelter residents would be married to Taliban fighters. The report also said that “sources reported the Taliban were conducting ‘audits’ of women’s shelters and women’s rights organizations, including those that provided protection services, enforced with intimidation through the brandishing of weapons and threats of violence.”

A month later, in October 2021, the UN secured $1.2 billion in emergency support for Afghanistan, but there were no assurances that any of the funds would go toward protecting Afghan women or girls.

The Khadijah Project was born out of necessity after the Taliban’s return. Seyedali, who has since transitioned from CEO to president of the nonprofit’s board, tells me that she didn’t intend to start a shelter back in 2021, but when a family who had a daughter that a Taliban member wanted to marry reached out to her, she didn’t have a choice. “The whole family was seeking refuge,” she says. “We worked with that family to develop our first home, and the eldest daughter went on to become our manager.” Since then, The Khadijah Project has grown from a single shelter to 60 homes, with funding from over 500 individual donors and independent foundations, along with human rights advocates such as Angelina Jolie.

The project was founded by a group of women in Afghanistan, and the staff today is comprised mostly of women, many of whom found refuge in the shelters themselves. “Our first three managers came to The Khadijah Project for help, so they understand how people are feeling when they arrive and what they really need,” Seyedali says.

Razia is now a manager with The Khadijah Project. She says that the women and girls arrive at the shelter traumatized by their experiences. “They are scared and deeply sad.” They have just landed in a new province, far from anyone they know. Razia can relate—it’s how she felt when she arrived at The Khadijah Project. “It’s really hard to not be able to go anywhere and to think how to move forward with my life,” she remembers.

She says that when she and other Khadijah staff members visit the women, she tells them her story to help build trust and instill hope. “When they hear my story, they feel they are not suffering alone. They are not isolated,” Razia says. In return, the women started sharing their stories with her. “They began to feel comfortable and trust us, and I think that was because we treated them like our own sisters and we got closer and became a big family,” she adds.

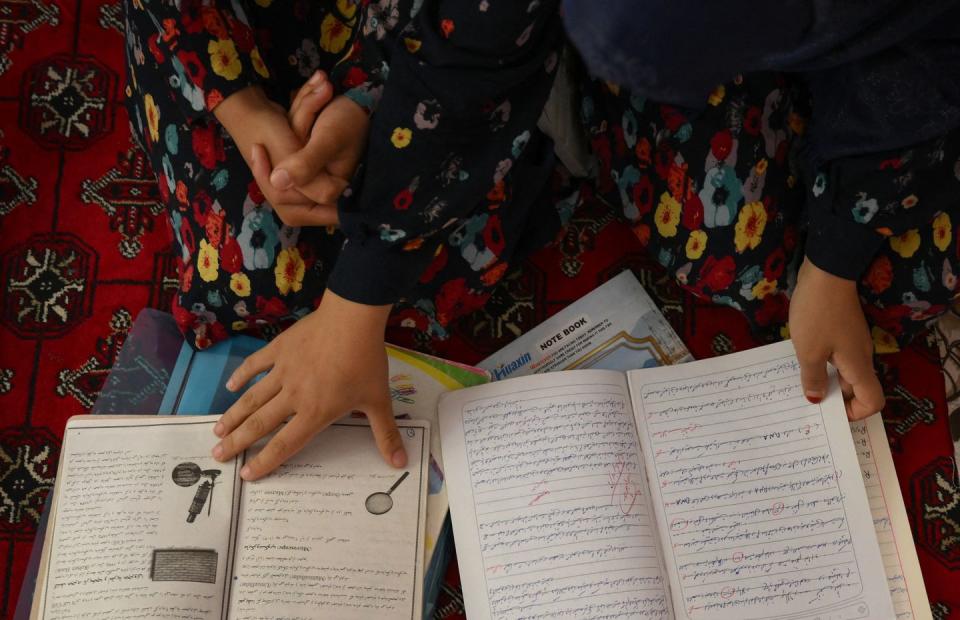

The staff take the time to ensure the girls feel comfortable in her new living situation, calling them daily and visiting them once a week, Razia says, to bring them food, pay their rent, and often deliver school books and other materials for their children.

Most of the women who come to The Khadijah Project are single women without a male chaperone (or mahram). “Living in Afghanistan without a mahram is very difficult,” Razia says. “In the minds of the Taliban, these women are incomplete.” Rental contracts need to be in the name of a man, and women are being stopped on the streets when they travel without a chaperone, making it very difficult to seek help privately, particularly if their abuser is a man within their family.

In opening their own shelters, The Khadijah Project aimed to address two glaring issues with the previous system. Under the former government, women could not bring any male children over the age of 12 with them to the shelters. This policy was meant to protect women, but in reality, it broke up families and meant that shelters could never be a viable solution for many women with sons, Seyedali explains. At The Khadijah Project’s shelters, women are allowed to bring their young sons with them.

The second problem they tackled was how to house large numbers of women and families together without everyone feeling like they were living in a dormitory. Seyedali says rather than dorms, The Khadijah Project gives women and girls their own rooms in individual houses to give them a feeling of safety and security. “Essentially, what we do have are family homes, we support women-led or majority-female families. Often it’s a woman who has suffered abuse or her husband has left her and her kids and she has no income,” Seyedali says. “We take the whole family on, work out a budget for them, and support their mental and physical health care and education.”

The Khadijah Project provides a variety of services based on what residents need. Sometimes it’s just a matter of paying a debt, so that a family doesn’t sell their daughter, Seyedali says. “The worse off the family is, the more likely they are to give their daughter in marriage for a bride price,” she says. “The more dire the circumstances, the younger they will [be when they] do this.”

Afghanistan’s deeply patriarchal society has meant that violence against women—in particular, domestic violence—has long been widespread. According to the Afghan Ministry of Women’s Affairs’ 2016 strategy on eliminating violence against women, more than half of all Afghan women reported experiencing at least one type of physical, sexual, or psychological violence, and more than 60 percent were married without their consent.

Many of the problems existed long before the Taliban takeover, at varying levels. A 2021 U.S. State Department report said that under the former government “at times, women in need of protection ended up in prison, either because their community lacked a protection center or because ‘running away’ was interpreted as a moral crime.” And Afghanistan has faced roadblocks and controversies ranging from who had control over the womens’ shelters to a lack of implementation of the laws designed to protect Afghan women from domestic abuse, forced marriage, and similar offenses.

Today, vulnerable women have few options to turn to when fleeing gender-based violence. Complaints of such violence are predominantly handled by male police and justice personnel, and the few mechanisms and policies enabling women to obtain legal redress and protection have “all but disappeared,” according to a December 2023 UN report. The Taliban have not established procedures for how to deal with such cases. Taliban officials quoted in the report said that women need to be with their husbands or other male family members, not in shelters. They also said that women were being sent to prison, allegedly for their own safety, or in instances where women had no male chaperone with whom they could stay.

Officially filing a complaint has always been complicated for Afghan women. In the past, women could go to the Ministry of Women’s Affairs to report domestic violence, but the Taliban replaced the ministry with the headquarters for its “morality police,” the Ministry for Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. The Ministry of Interior’s “Family Response Units,” which had helped women register complaints with the police, have also closed in some provinces; the department of women’s protection centers no longer exists; and there is no legal aid or protections for women fleeing abuse. Many female prosecutors, judges, and lawyers who had once tried to provide women a measure of justice are now in hiding or have left the country.

Seyedali says that around 40 percent of cases at The Khadijah Project involve domestic violence, while another 30 percent are widows and single women who cannot support their families or women from families that have lost their primary means of income, including former government workers. “The women want to learn skills, they want to earn a living—that’s the next part of our program,” Seyedali says of her plans for the future.

The shelters cannot support the women forever. “The ultimate problem with the shelter model is they never figured out a real exit strategy. There was so much funding to build shelters and take women in,” Seyedali says of the level of international investment during the war. “But not a lot of progress on what happens if women exit.”

The Khadijah Project is working to prepare the women to be able to support themselves, when they are ready to leave the shelter. “We’re trying to put families on a 12-month plan, so they can work towards becoming independent,” but in order to build the model, she says they need consistent, long-term, reliable funding.

The lack of international funding has exacerbated the crisis; with the big international players no longer on the ground, grassroot women’s organizations like The Khadijah Project are now facing a myriad of hurdles to obtain funding, Seyedali says. Prior to the Taliban takeover, funding would go either directly to local NGOs, or it would trickle down to them through international NGOs, the UN, or the Afghan government’s Ministry of Women’s Affairs, she explains. The systems for assistance and funding are now in complete disarray. “We still don’t have robust referral systems to connect local organizations with international agencies. It’s this massive gap,” says Seyedali.

Even after grants are awarded, she says that the promised money often doesn’t appear or there are long delays. In August 2022, for example, The Khadijah Project was selected to receive a $200,000 grant from the UN to cover the project’s annual running costs. But it was a year before they received a portion of the money, Seyedali says.

Despite having nearly three years to adjust to the new context, Seyedali says that the systems in place for distributing money to organizations working on the ground are needlessly complicated and opaque. Applicants are expected to have high levels of English and a deep understanding of how International NGO grant applications work. “The most eligible for this grant are displaced young women, which we are, but they were asking our staff how many master’s degrees they have and whether we have a professional auditor and so on. I feel like they’re setting up hurdles that you can’t pass on purpose. They’re making it impossible.”

The year-long wait for the funds has been catastrophic for the project, as well as the women they support. Without the funds, The Khadijah Project had to downsize from 60 small shelters to about 25, which, as of last month, support 270 women and children, Seyedali says. Now that they have received some of the funds, they are trying to build up the number of shelters again. The need is immense, she adds.

In June 2023, as the first of the sticky summer heat starts to warm Kabul, an ice cream seller announces his arrival as he rolls his cart down the capital city’s narrow streets. A woman named Hasiba (a pseudonym) peeks out from behind heavy curtains at the jubilant children flooding out to meet him, before pulling them tightly shut again, plunging herself back into darkness.

The forty-something woman came to a Khadijah Project shelter two years ago with her two sons, daughter, and her two-year-old granddaughter. Five months before Hasiba arrived in Kabul, on March 8, 2021, armed men kicked in her door, and murdered her son-in-law in front of his family. “They wanted to kill me because I was a major in the Afghan Army, but I wasn’t at home at the time, so they killed him,” Hasiba explains, “he was also in the army,” she adds, looking down at her hands. She tells me she knew it was the Taliban, because they had been sending her threatening letters.

Months later, the Taliban took over Hasiba’s home province. She brought bus tickets for her family the same day, and they left their home.

Hasiba arrived in Kabul, hundreds of miles away, and with nowhere to go, she called her American trainer for help. The trainer connected her with The Khadijah Project, where she could seek refuge with her children.

Now, the shelter has become their new home, but Hasiba says that they are only just starting to feel safe. “It was so hard to leave our home. My sons left their school, friends and relatives, and are in a new province, but they are trying to adjust,” she says, “but at least we are all together here, as a family.”

While the issue of gender-based violence shows no sign of abating in Afghanistan, for those who have fled their homes, facing uncertainty, the shelters offer a bare minimum of safety. If they are closed, however, that too, will disappear. The future of these shelters, and the woman they support, is a critical part of the struggle for gender equality in Afghanistan, and a test of the Taliban’s capacity and willingness to tackle violence against women and girls.

Although the few organizations like The Khadijah Project remain a lifeline for women and girl—when they have funding, that is—they are, in the end, only allowed to operate with the Taliban government’s permission and according to their rules.

Nearly a year after I first spoke with Hasiba, she is still at the shelter in Kabul with her children and granddaughter. She brought her sons’ school books so they can continue their education, but they don’t leave the shelter, as she still fears for their safety. “We are living like a person in a jail. It’s hard to be here and not know when we can leave or what will be in our futures,” she says. “I cannot work and my children are too young to work, so we are stuck. Right now, I don’t have any hope for our futures in Afghanistan, only worry.”

You Might Also Like

Yahoo News

Yahoo News