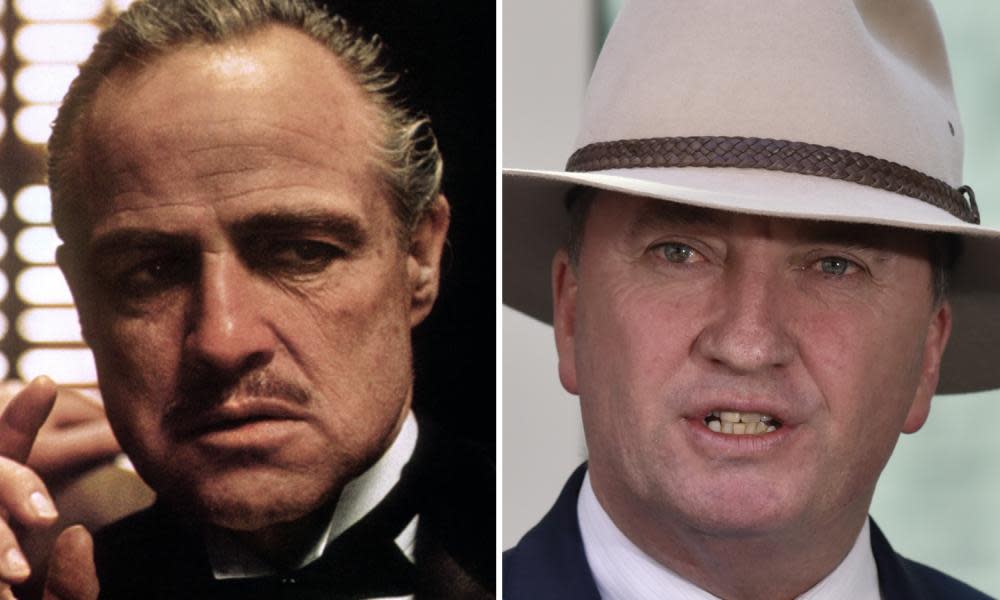

Another reason for Barnaby Joyce to be jealous of Marlon Brando

This week was all about being distracted by thoughts of famous people’s sex lives. I know more than I ever wanted to know about Australian deputy prime minister Barnaby Joyce’s, but still couldn’t stop reading. And less reluctantly I read everything I could – spurred by Quincy Jones’s remarkable interview – about Marlon Brando’s and Richard Pryor’s, and which one would have sex with a letterbox and which one with a radiator.

“Brando used to go cha-cha dancing with us. He could dance his ass off. He was the most charming motherfucker you ever met. He’d fuck anything. Anything! He’d fuck a mailbox. James Baldwin. Richard Pryor. Marvin Gaye,” Jones said.

It seems a miracle that two of the most famous men of the 1970s were able to have sex with each other under the radar. That and the Joyce interview got me thinking about privacy.

Joyce’s plea this week on the ABC’s 7.30 program that his affair with Vikki Campion was a “deeply private matter” – didn’t gain much traction. There are considerations, other than sex, that ensured it didn’t – including his use of a rent-free house and Campion being given staffer jobs. Joyce’s campaigning for family values – and against same-sex marriage – exposed him to a charge of hypocrisy too.

But I wonder if Campion, Joyce and his family are victims of the drifts of time, and our changing notion of privacy. Privacy now is becoming as much of a relic as doing the cha-cha.

The super-rich buy it and guard it – they have the funds to enforce their rights under defamation laws, they employ people to manage their social media or leave it, if it starts to annoy them. Unlike us mortals, they do not need to be constantly breaching their own privacy – sharing more and more of themselves in order to build up a brand or keep relevant or up-to-date in their professions.

But, for the average person, participation in the digital age has resulted in bathroom mirror and bed hair selfies and constant status updates. The bedroom door that used be shut to the world is now wide open.

The digital age has also meant the relinquishment of data that situates us not just in time and space (such location tracking data) but monitors our consumer habits, our desires and ideology (including targeted political ads on Facebook).

On television we watch, without comment or concern now, programs that constantly film and monitor participants – an always-on eye trained to contestants as they shower, eat and sleep, hoping to catch an intimate or unguarded moment that will move the narrative forward until the next night.

Then there’s the state’s and corporations’ disregard for privacy – with their industrial appetite for CCTV, data scraping and legislation that chips away at civil liberties.

All this we know, and most of us are unmoved.

But there’s another major factor at play – society’s shift away from liberalism and towards so-called identity politics – which posits privacy itself as suspect, as a shield for potential hypocrisy.

Identity politics requires you dismantle the Chinese walls in your life. Who you sleep with, your vote, how you celebrate public holidays (such as Australia Day), what products you consume – all signal your political identity. Support Indigenous rights by posting on Facebook memes of an Invasion Day march but still go for piss-up and barbecue for Australia Day? These days that seems a bit … off, the duality unsupportable. The personal is political again.

This week in New York magazine – referencing not Brando and Barnaby but #MeToo, campus politics and the comedian Aziz Ansari – columnist Andrew Sullivan called time on liberalism and the enlightenment project. He argued that social justice politics, intersectionality and identity politics have trumped liberal values that included the right to a private life and instead the “core truth of our society is a system of interlocking and oppressive power structures based around immutable characteristics like race or sex or sexual orientation”. The piece lamented this shift and the consequences for privacy.

Liberalism making way for identity politics is not necessarily a cause for hand-wringing – after all, identity politics seeks to redress the deeper structural issues that cause inequality, things that liberalism hasn’t had enough muscle to shift. Like men, women and the whole power dynamics around consent. Like the whole the Ansari thing, in a nutshell, where a woman who went on a date with him accused him of sexual assault, which he said he believed was consensual. Sullivan believes Ansari’s privacy was violated.

After what was reported, can Ansari go back to a third season of Master of None portraying himself as a woke dude? Or will his character’s storyline become something darker but more real?

But in his lament, Sullivan has also hit upon a point. There are consequences when you erode privacy. It affects everything from those who run for public office (do these new standards and transparency mean that anyone with a “past” will be put off?) to demanding a standard of purity and consistency that is in fact inconsistent with being human.

I offer myself as a case in point – I support the right to privacy, as I support transparency and consistency, as I have also gobbled up all the juicy sex scandals of the past week (each day I read the Daily Telegraph! Go Sharri!). I’m only human.

It’s not hypocrisy, but an acknowledgment of our simultaneous multiple selves, like two or more scripts running at once, but not overriding each other.

Brigid Delaney is a Guardian Australian columnist

Yahoo News

Yahoo News