'It's dire': farmers battle their worst drought in 100 years – photo essay

“It’s a pretty tough old time,” says Coonabarabran farmer Ambrose Doolan. “But if you’re working with your family and everyone is looking out for each other, you count your blessings.” In the central-west region of New South Wales, farmers continue to battle a crippling drought that many locals are calling the worst since 1902. In Warrumbungle shire, where sharp peaks fall away to once fertile farmland, the small town of Coonabarabran is running out of water. The town dam has fallen to 23% of its capacity and residents are living with level-six water restrictions. There are real fears the town will run dry.

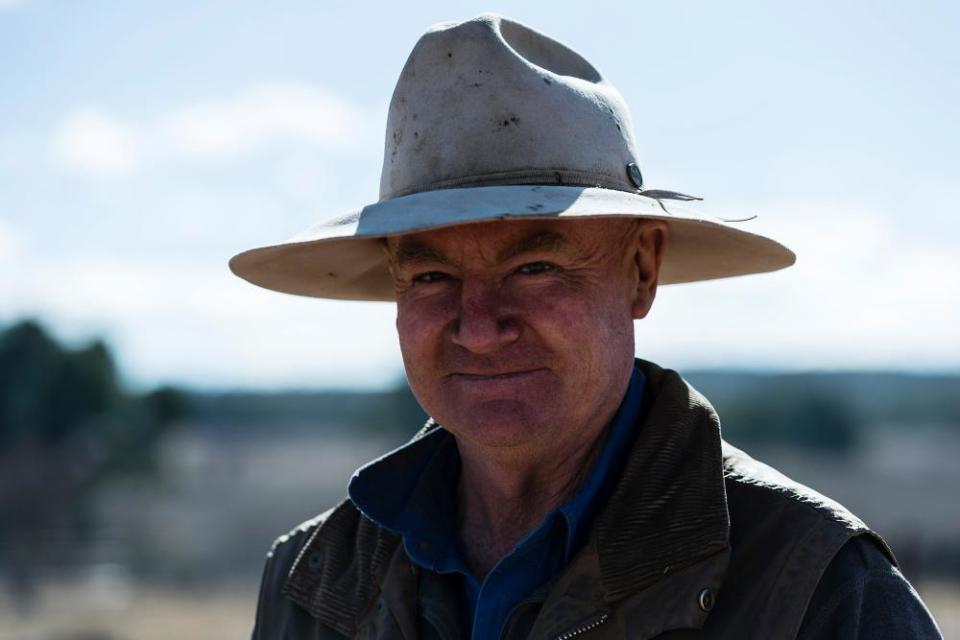

Clockwise from top: An aerial view of the cattle feeding operation on the property Toorawandi, and Ambrose Doolan.

Doolan and his wife, Lisa, run 9,000 acres with Angus cattle outside of the town on their property, Toorawandi. Their son Mick has followed them into the farming business and has his own property, and their daughter Emily, a town planner, returned home this year to work on the family farm. “What a year to do it,” Doolan says. “My dad didn’t want me to be a farmer and I think this is why. We were a bit the same with our son, we didn’t want him to be a farmer. But you are what you are.”

Clockwise from top: Ambrose Doolan works on their property outside Coonabrabran, and an aerial view of the cattle-feeding operation.

My dad didn’t want me to be a farmer and I think this is why.

Ambrose Doolan

Last year the Doolans recorded their fourth-lowest average rainfall and it has been followed by even drier conditions. They have sold whatever stock they can and spend their entire days at the moment feeding the cattle that remains because the pastures have dried up.

Clockwise from top: Harry Taylor plays on the dust bowl, and sheep on the Taylor family farm.

Farmers in this part of NSW are importing almost all food for their livestock from as far away as South Australia as prices rise with demand. The continued cost of buying feed is causing many to question their future on the land. The NSW government recently approved an emergency drought relief package of $600m, at least $250m of which will cover low-interest loans to assist eligible farm businesses to recover. The package has been welcomed but, in the words of a local farmer, “it barely touches the sides”. With the prospect of a dry El Niño weather pattern hitting the state in spring, the longer-term outlook is dire.

Clockwise from top: Jessica Taylor, with Bony, 18 months, and Charlie, 4.

Jess Taylor and her husband, Robert, are fourth-generation farmers, running a mixed sheep and cattle farm 25km north-west of Coonabarabran. They are raising four children, two not yet in school, while dealing with the stress of nearly two years without substantial rain. Bills from trucking in food for their sheep and cattle are running as high as $20,000 a month.

Clockwise from top: Heidi and Harry Taylor play in one of the many empty dams on their family farm, Jess Taylor at work on the family farm, Heidi and Harry play near the bones of dead livestock, and Robert Taylor scrapes the last of the families grain stores out to feed livestock.

Robert left the property recently to take up shearing work to bring in much-needed cash, leaving Jess to manage the farm and care for their children on her own. “There’s just no income. Whatever the farm is making is going back into feed for whatever we have left,” she says. “It’s hard, it’s hard to know what to do.”

Harry Taylor, 6, picks up a lamb to try and feed it cotton seed.

The family sold their healthier stock last year before the market “took a huge dive”, Jess says. The ewes on the property are abandoning their lambs because the dry pastures and lack of food have reduced their ability to produce enough milk. “We’ve got close to 30 orphan lambs that we’re hand-feeding,” Jess says. “We lost quite a few of them in the cold snap that just came through despite doing the best we could for them.”

The family takes a sheep orphaned from the flock to the house.

The sheep on the dry land of the Maryborough property.

Charities such as Buy a Bale, where people can purchase hay bales for local farmers, have been some assistance. The Taylors’ oldest son, Harry, asked for rain for his sixth birthday. While much of NSW experienced a wet start to winter, the dark skies over Coonabarabran have yet to deliver relief. The Taylors say they will not be taking up the government’s loan, as they are already struggling with considerable debt.

Financially, we’re on our borderline now

Greg Jerry

Coral Jerry, 80, on the family farm

The Jerry family, also fourth-generation farmers, run sheep and cattle on their property Maryborough, 40km north-east of Coonabarabran. At the head of the family is Coral Jerry, 80, who lives on the farm alone after her husband of 55 years died in 2015. She is hand-feeding 40 orphaned lambs four to five times a day while her son Greg, his wife, Tanya, and their son Brett manage the farm.

Clockwise from top: The Jerry family farm Maryborough, and Coral Jerry, 80, feeding a lamb.

Things have become so desperate the Jerrys are mixing expired baby formula with their imported cotton seed to add nutrition for their struggling animals. “It’s a never-ending story at the moment,” Greg says. “Every week there’s a chance of some sort of rain but when it happens it’s usually one or two mils, which does nothing ... We actually got 19 mils the other day, which was beautiful.”

Greg Jerry on the farm. The load of wool pictured is the last income the family expects from the farm for another 12 months, sheep eating expired baby formula with imported cotton seed, sheep following the family truck, and Tanya Jerry cares for a sheep to weak to eat.

He says it would take 100mm of rain to deliver long-term improvement to a property that currently “looks a bit like the surface of the moon”. “Financially, we’re on our borderline now,” he says. “We destocked as much as possible early on as it got worse and worse. But what we’re left with now is pretty much unsaleable in the condition they’re in.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News