'A way of learning from everything': the rise of the city critic

“On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy,” wrote EB White in his 1949 essay, Here Is New York.

White sizes up both the positive and negative potential of the teeming Manhattan with the familiarity of a native and the heightened awareness of a visitor. A longtime contributor to the New Yorker magazine, White also wrote the classic children’s book Charlotte’s Web and co-wrote the influential writing guide The Elements of Style. In Here Is New York, he takes that versatility further, giving us a new way of seeing the city in an early example of what we might today call city criticism.

Given how long we’ve relied on the work of critics on film, music, food, and much else besides, as well as the ever-increasing relevance of cities in our lives, it’s time we recognised city criticism as its own distinct category of writing. But what is city criticism — or rather, what isn’t it?

Despite dealing with the built environment, it isn’t architecture criticism, not in the sense of treating structures like sculptures, indulging in a “collective obsession with idiosyncratic starchitect buildings,” writes Globe and Mail architecture critic Alex Bozikovic. Architecture matters in city criticism only to the extent that it explores “what’s designed and built in the context of a broader narrative,” writes Curbed urbanism editor Alissa Walker. “What’s happening in the surrounding community, what political efforts hindered progress, and, conceding all those externalities, can the project still best serve the audience that it is intended to serve?”

To Walker, city criticism isn’t about buildings, but about people: a city critic must be “someone who’s going to all the public meetings and listening to what all the elected officials say, [but also] out in the city itself, riding buses, hanging out at coffee shops, talking to people about how that policy affects them.”

Yet city criticism isn’t reportage. Like movie or restaurant reviewers, city critics write from their own perspectives, in distinctive voices enriched by knowledge and experience, but wearing their erudition lightly. City critics understand that places reveal themselves through details encountered by chance, glimpsed and overheard.

Iain Sinclair’s lifetime of walking London has produced a series of books notable for their intensity, as well as their density, of historical, cultural, and political observations. Whether the length of the entire M25 or of Sinclair’s neighbourhood of Hackney, his walks lead to disquisitions on not just redevelopment, gentrification and bus routes, but terrorism and asylums and alchemy and Hitchcock – as well as furious denunciations of London’s latter-day disfigurement by money and mega-projects.

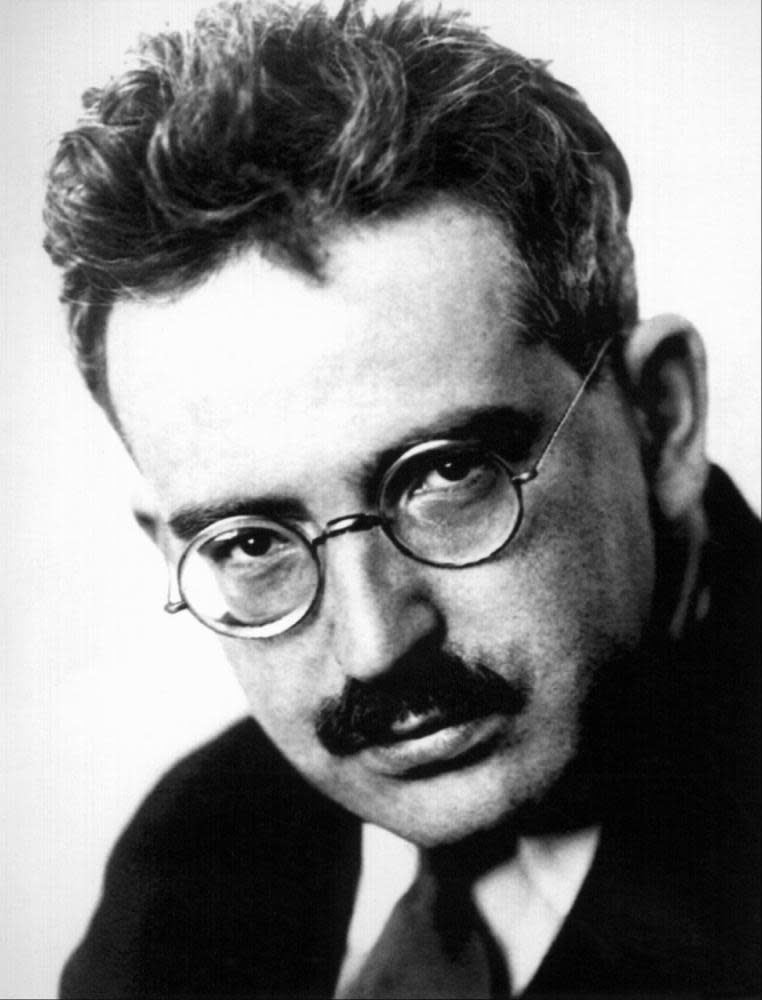

The term psychogeography, long associated with Sinclair’s work, has gone unexpectedly mainstream: many now apply it to their own artistic and peripatetic endeavours as they once called themselves flâneurs, those who walk city streets to observe urban society. In Lights Out for the Territory Sinclair describes the flâneur as “a stubborn creature, less interested in texture and fabric, eavesdropping on philosophical conversation pieces than noticing everything.” That mandate, taken on by German philosopher and essayist Walter Benjamin decades earlier, resulted in The Arcades Project: a densely referential, nearly thousand-page examination of the shopping arcades of late 19th- and early 20th-century Paris, perhaps the first and most ambitious work of city criticism.

The Arcades Project was left unfinished at the time of Benjamin’s death in 1940. Here Is New York came at the end of that decade, and 1961 saw the publication of two volumes that still have much to teach us about the possibilities of city criticism: urban historian Lewis Mumford’s The City in History, which puts cities in context, and journalist Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which makes them a subject of activism.

The most intellectually daring and flamboyant venture into city criticism yet came ten years thereafter, when architectural historian Reyner Banham wrote Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, a contrarian yet enduring analysis of and argument for a place most critics and other city-minded intellectuals had long written off as a dysfunctional and tasteless, a grotesquely overgrown postwar suburb.

“Los Angeles threatens the intellectual repose and professional livelihood of many architects, artists, planners, and environmentalists because it breaks the rules of urban design that they promulgate in works and writings and teach to their students,” writes Banham:

In so far as Los Angeles performs the functions of a great city, in terms of size, cosmopolitan style, creative energy, international influence, distinctive way of life and corporate personality, to the extent that Los Angeles has these qualities, then to that same extent all the most admired theorists of the present century, from the Futurists and Le Corbusier to Jane Jacobs and Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, have been wrong.”

Welsh travel writer Jan Morris went beyond the single city in an attempt to describe “the entire urban world”. The project led her to the lively but haunting rebuilt Hiroshima – missing an essential element “like salt with your victuals, or eyes in a beautiful face” – and to London, where “through the dingy and the disagreeable, the fantastic habitually looms.” Hong Kong she found “indefensible, militarily and economically, and it lives half on trust and half on cynicism,” while of her beloved Venice, which since the turn of the 19th century “has chiefly existed to be stared at”, she declared: “Let her sink.”

City criticism is not travel writing, but it should take Morris’ work as a model of how to let readers see a city through the writer’s eyes. It should also pry loose the clichés that inevitably adhere to a place, as when Morris came to Los Angeles, eschewed references to stardom and sprawl, and described the city as where “the lost American faith in machines and materialism built its own astonishing monument.”

Sometimes city criticism has tangible effects. Nearly 60 years after its publication, The Death and Life of Great American Cities continues to open readers’ eyes to the unplanned “ballet of the good city sidewalk” that Jacobs observed in her native New York City: in the students, shop owners, commuters and delivery people, “the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole”.

But Jacobs also raised the alarm about the threatened eradication of that finely grained street life by New York’s so-called master builder of freeways and high-rises, the urban planner Robert Moses. Later in the decade, she got involved in the struggle against Moses, repeatedly protesting against his plan to run the Lower Manhattan Expressway through her neighbourhood of Greenwich Village. After fighting the project to its death she moved to Toronto, a city that provided more subjects for her criticism and more development projects – a new freeway, a waterfront bridge – to publicly oppose.

Some city critics will follow Jacobs’ example and seek to influence the shape of cities, while others will seek only to understand it. The architects Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour exemplify that method in 1972’s Learning from Las Vegas, a subject they felt obliged to justify: “We look backward at history and tradition to go forward; we can also look downward to go upward,” they write. “Withholding judgment may be used as a tool to make later judgment more sensitive. This is a way of learning from everything.”

Indeed, city critics should write about everything: their subject is a nexus of subjects. Ada Louise Huxtable concerned herself with not just her official beat of architecture at the New York Times and later the Wall Street Journal, but also development economics and the policy of land use and transportation; the ultra-opinionated Ian Nairn savaged postwar Britain’s uninspired buildings and even less inspired city planning; the New Yorker’s architecture critic Mumford wrote about highways, housing and planning, but also literature, technology and politics. And longtime writer on the built environment Karrie Jacobs points out that most writers on cities currently “either focus on urban problems or urban pleasures,” whereas “in truth, the problems and the pleasures have a symbiotic relationship,” which any critic worthy of the title understands.

What would a more fully developed city criticism have to offer? Most who write about cities agree on one thing: helping effect change. The British writer Owen Hatherly, a sometime Guardian Cities contributor who has looked often at post-Soviet urban landscapes, argues for city criticism to “help us understand cities, and how they have been shaped by very particular decisions, choices and interests, and that they can be changed, influenced and transformed in turn.” Nikil Saval, the Indian-American writer, puts capitalism in his crosshairs, since “you can often see examples of our economic system’s mutations and depredations in how cities and city politics work”. Spacing magazine’s Shawn Micallef sees his mission “to get people to really see, experience and live their city,” since they “won’t fight for something to be better if they haven’t yet fallen in love with it.” Walker underscores the importance of advocating for “the people who keep the city running.”

Related: How Jane Jacobs changed the way we look at cities | Saskia Sassen

But city critics should be be writers above all else. And though the past decade has seen an abundance of city-related content in print and online, cities need writers more than ever. That is, cities need to be written about well and in a way that lasts, not merely to spot trends, air grievances, or enter technocratic squabbles. Readers will only tolerate so much more one-dimensional discussion before developing city fatigue, and history has shown what happens to cities when the public loses interest in them. Hence the city critic’s mandate to keep readers engaged and thinking in the long term by treating the city as not just as a fashionable place to live and work, nor as an ideological, economic, and social battleground, but as one of the very richest, most stimulating subjects available.

Unlike service journalism, city criticism must remain fresh while the city changes over time; unlike academic theory, it must be written for the general public; unlike activism, it must keep the distance necessary for keen, aesthetically sensitive observation. City critics must be invested in not just buildings, infrastructure, and public space, but in words, sentences, and the play of ideas. Only then can they write like EB White did on New York’s paradoxical generosity of privacy:

It is this largesse that accounts for the presence within the city’s walls of a considerable section of the population; for the residents of Manhattan are to a large extent strangers who have pulled up stakes somewhere and come to town, seeking sanctuary or fulfilment or some greater or lesser grail. The capacity to make such dubious gifs is a mysterious quality of New York. It can destroy an individual, or it can fulfil him, depending a good deal on luck.”

Despite having been written 70 years ago, the observation holds up today – though city critics to come, taking a page from each of these writers and others besides, should feel free to argue otherwise.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, catch up on our best stories or sign up for our weekly newsletter

Yahoo News

Yahoo News