Auguste Rodin facts: 5 things you didn't know ahead of British Museum exhibition

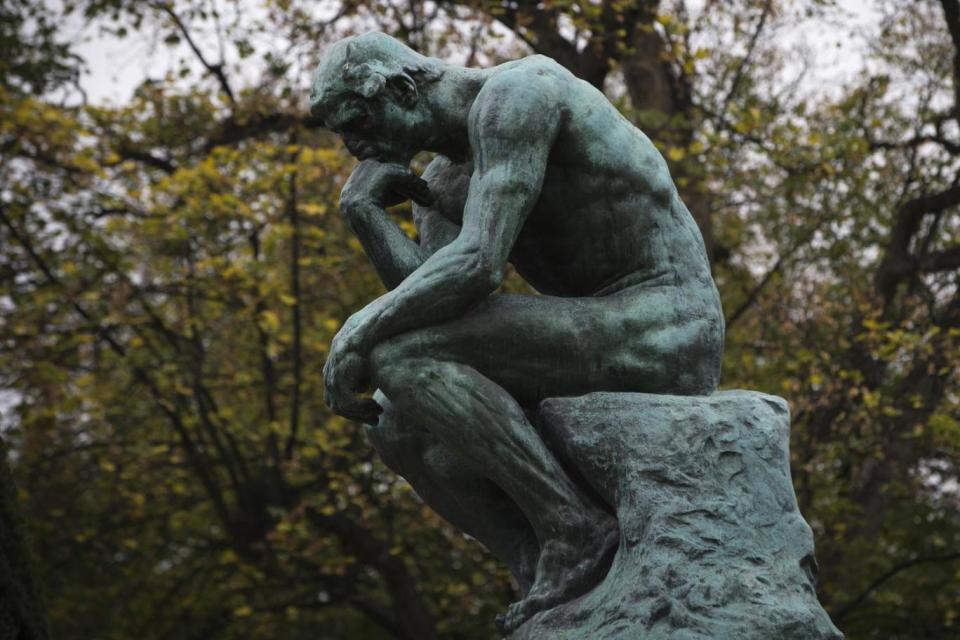

From passionate kisses to figures lost in thought, Auguste Rodin's sculptures are some of the most famous in the world.

The French artist defied his critics to pursue the human figure in a more expressive, less idealised and more realistic way than was typical of his contemporaries, and his work went on to inspire the beginnings of modernist sculpture.

You may know The Thinker, you may know The Kiss, but do you know the secrets behind them?

As the British Museum opens a new exhibition of Rodin’s work this week, here's your chance swot up on the things you may not have known about one of the world’s most influential sculptors.

Rodin had pretty bad eyesight

Auguste Rodin changed the way sculpture looked in the late nineteenth century – making it even more surprising that he did so whilst not being able to see particularly well. As a child, Rodin struggled at school due to poor long distance eyesight. The problem plagued him throughout his life, and he was even asked to leave the French army due to his near-sightedness. These setbacks were, however, what drew Rodin into his artistic career. Having swerved maths and literacy for drawing in his school years, his rejection from the army forced him to continue pursuing his art rather than taking on national service.

He was obsessed with the British Museum

The British Museum, an institution best known for showing artefacts harking back thousands of years, might sound like an odd venue for an exhibition of work by a turn-of-the-century sculptor. Auguste Rodin, however, would have been thrilled, as he was a great fan of the museum. The Frenchman first visited the London museum in 1881, where his first meeting with the headless, limbless ancient Greek sculptures of the Parthenon had a profound effect on his work. He would visit numerous times from then on, fascinated by the museum’s world class collection.

He didn’t actually carve his marble sculptures

When you think of Rodin, your first thought may be of the effervescent pale figures locked in embrace in his work The Kiss. But while many of his most famous works are made from marble, Rodin himself rarely touched the stuff. The sculptor preferred using the tactile process of working with clay to model his subjects. He would then pass his clay model on to his assistants, who would recreate and often enlarge them, either by casting them in bronze or carving them from marble.

The Thinker started out as part of a door frame

The Thinker is best known as a monumental, larger-than-life figure, but the origins of the Rodin’s best known work were actually a little more humble. The iconic, hunched male nude started life as the centre piece of a doorway Rodin was commissioned to make for the Directorate of Fine Arts. Known as The Gates of Hell, the doorway depicts scenes from Dante’s Inferno. The Thinker as we know him was initially The Poet, a model of Dante that was positioned above the centre, looking down on those who walked through the fiery gates.

The couple in The Kiss don’t actually kiss

The Kiss is actually a bit of a misnomer. This sculpture by Rodin also started life as part of The Gates of Hell, and depicts another scene from Dante’s Inferno. In the epic poem, Francesca da Rimini falls for Paolo Malatesta, the younger brother of her husband Giovanni. The sculpture captures the moment Francesca and Paolo succumb to their feelings for one another and go to kiss – before Giovanni discovers them and kills them both. If you look at the sculpture from above, you can see that their lips never quite get to touch.

Rodin and the art of ancient Greece, supported by Bank of America Merrill Lynch, runs from April 26 - July 29 2018. For more information visit britishmuseum.org

Yahoo News

Yahoo News