Babs Windsor: the daring, giggling pearly queen of the screen

When Barbara Deeks, a 16-year-old actor from east London, was encouraged to choose a stage name in 1953, it might seem arrogant that she borrowed from the newly crowned Queen of the United Kingdom.

Related: Barbara Windsor: a life in pictures

As it turned out, though, the cheeky moniker proved prophetic. It grew to seem entirely fitting that the long-serving monarch should share a surname with a woman who became showbiz aristocracy. She was accepted as British acting’s Pearly Queen – her Cockney accent and background always important to her career-defining roles – long before Elizabeth II conferred on her the title of Dame of the British Empire in 2016.

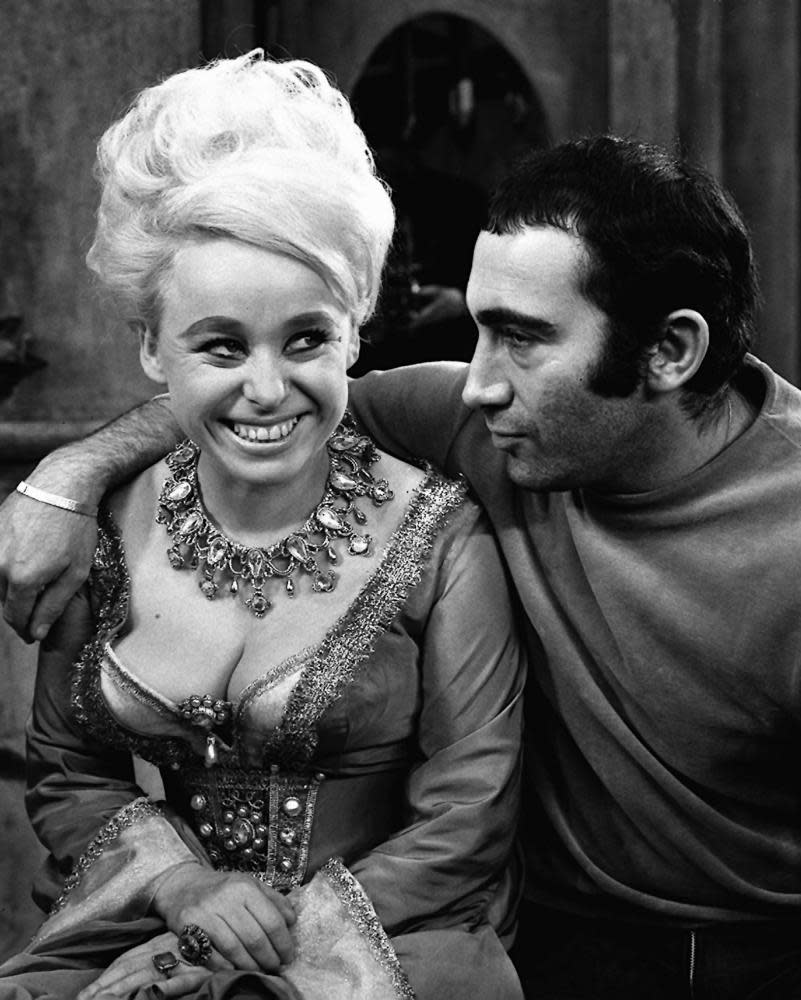

Her status was sealed by three classic franchises. “Babs”, as she was commonly known, was one of the most significant figures in one of British cinema’s defining series. She appeared in nine Carry On films, built around cleavage and smutty double meanings.

On television, Windsor was seen over 22 years in BBC1’s EastEnders, as Peggy Mitchell, matriarch of the Albert Square clan who ran the Queen Vic pub.

And, although this was less remembered than she would have liked, Barbara, before her screen celebrity, had been in the early 1950s a core member of one of the UK’s most significant and influential theatre groups: the Theatre Workshop, established in London’s Stratford East by director Joan Littlewood to create inventive, politically engaged popular theatre.

Barbara Ann Deeks began her acting career as a child. She was given dance and singing lessons by her mother as a distracting treat from the marital troubles of Rose, dressmaker, and John, a costermonger. Young Barbara revealed such natural and enthusiastic theatricality that she was accepted by the Aida Foster Theatre school, a leading London acting academy, appearing in the chorus line of a West End show aged 15 and playing one of the feral schoolgirls in the 1954 film, The Belles of St Trinian’s.

Although often patronised by critics and profilers because of the mass entertainment screen roles that made her famous, it is a measure of Windsor’s talent that she was recruited by Littlewood, a tough judge of actors, who valued authenticity and versatility. Windsor featured in three key Theatre Workshop pieces: Lionel Bart’s Cockney musical Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’be (1960); the play Sparrers Can’t Sing which became the movie Sparrows Can’t Sing (1960/’63), and the Broadway version of Littlewood’s biggest hit, Oh, What a Lovely War! (1965). Her Tony award nomination for that performance – and Bafta nomination for Sparrows – are a testimony to the seriousness of her craft.

Her public reputation was shaped, though, by Carry On. Presciently entwining what would become two indelible pieces of British cinematic history, the first film in the franchise, Carry on Spying (1964), was a parody of early James Bond.

Windsor played a femme fatale called Daphne Honeybutt, a nudge-nudge name that was ironically less risqué than that of Honeybutt’s inspiration, Pussy Galore, in Goldfinger, the 007 movie released in the same year.

While Windsor ultimately achieved real earning power at a time when few women in the British screen industries had it, she is a complicated case for feminists because her celebrity arose from the acceptability, at that time, of an actress being prized for her bum-wiggle, giggle and the size and visibility of her breasts. The moment in Carry on Camping, when the low-cut bikini top of Windsor’s character accidentally flies from her bust during a chest-stretching exercise class, became the actress’s signature moment. She confided to friends her regretful acceptance that this scene, which ends with the upper swimwear whiplashing Kenneth Williams in the face, would inevitably feature in her TV obituaries.

Williams admitted he initially disliked Windsor, perhaps because sexually confident Cockney women were outside his comfort zone. Rapidly, though, they became close friends, a tribute to the innate warmth, enthusiasm and professionalism that were central to Windsor’s personality. She was known on sets, and in public appearances, for democratic generosity towards people of all ranks.

Her eighth and final movie in the reputation-making series was Carry On Dick (1974). Although the title officially referred to the legendary highwayman, Richard Turpin, the blunt double-entendre reflected what Windsor saw as a coarsening of the material, which was the reason she gave for leaving the series.

Typecasting as a busty guffawer certainly restricted her subsequent possibilities, although she showed her considerable theatrical skills were intact as a libidinous landlady in a 1981 revival of Joe Orton’s dark comedy, Entertaining Mr Sloane, directed by Williams.

When the BBC launched EastEnders in 1985, many (including Windsor herself) saw it as an ideal vehicle for her as Cockney showbiz royalty. But the creators considered her too famous and too associated with comedy to suit the grimy realism to which they aspired. In 1994, though, a new producer asked Windsor to play Peggy Mitchell, the previously estranged mother of Albert Square’s gangster siblings, Grant and Phil. Another actor played Peggy in 1991, but it was soon apparent that Windsor and Mitchell were one of the great matches between player and part.

Windsor was almost too perfect casting as a “gangster’s moll.” The Mitchell brothers were a latter-day version of the actual notorious east London crime family, The Krays. Windsor had brief relationships with two of the Kray brothers, and was married for two decades to one of their younger acolytes, Ronnie Knight, who served a jail term for armed robbery after spending years in Spain as a fugitive from UK justice.

While there was never any suggestion that Windsor was herself complicit in crime, her closeness to those who were did sometimes shadow her public profile. The most charitable interpretation is that she was vulnerable to the “redemption syndrome”, by which good women hope to redeem dangerous men, and therefore risked being a “bad picker”. The consequences were personal – her memoirs revealed she had terminated five pregnancies, believing she was not fit to be a mother – and financial. She ended up in such debt she had to restore her finances with a one-woman autobiographical show, Carry on Barbara!, which was a national and international success, her easy charm again coming to the rescue.

Her private life notably improved when she married the actor Scott Mitchell in 2000. His being half her age invited scepticism, but their relationship was seen as happy and stable. Scott campaigned to raise money for research into the Alzheimer’s that blighted his wife’s final years, through which he became her carer.

Windsor’s impact was so vast that she was the subject of several biographical dramas. Terry Johnson’s 1998 play Cleo, Camping, Emmanuelle and Dick (its title featuring the final word of four Carry On movies) dramatised the brief affair between Windsor and leading man Sid James, who was almost twice her age, after she promised the lovestruck funnyman a one-night stand “to get me out of your system”, a strategy that backfired.

On the first night at the National Theatre, actor Samantha Spiro’s perfect imitation of the Windsor giggle was followed seconds later by the real thing, from Barbara sitting in the stalls. The echo was heard frequently because Windsor, though initially apprehensive, loved the show, which Johnson later adapted as a TV film, Cor, Blimey! (2000), with Spiro again inhabiting the character. Windsor told interviewers that, although she had never told the playwright the details of her pre and post-coital conversations with James, he had somehow accurately imagined them.

Poignantly, her final screen credit, before dementia enforced retirement, was in another version of her own life. In the BBC film Babs (2017), written by Tony Jordan, who had scripted some of her best scenes in EastEnders, Windsor played the older version of herself, with Spiro again taking the role through the middle-age years.

Having first appeared on stage as a child, her career spanned a remarkable 65 years. Although she will always be associated by some with the bikini catastrophe in Carry On Camping, she should properly be remembered for a significant body of work in cinema, theatre and TV.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News