Bankrupt coal giant turns to grass in Wyoming to cut liabilities

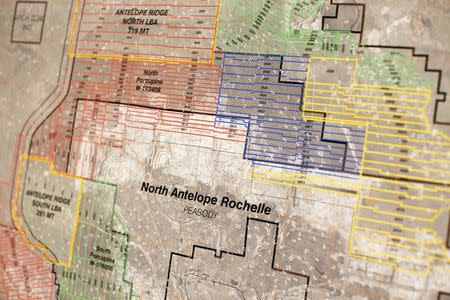

By Tracy Rucinski GILLETTE, Wyo. (Reuters) - A squad of about ten Peabody Energy Corp. miners clad in steel-toed boots and hard hats climbed into massive bulldozers on a recent morning, ready to create rolling hills of grass over former pits at the Rawhide coal mine in Wyoming. In the midst of a deep coal downturn and widespread layoffs, the staff that remains at Rawhide is spending more time in 2016 on landscaping than mining. "We're probably going to do four times the amount this year than we would normally do," said Mary DeRudder, a 30-year veteran coal miner at Rawhide, which saw its workforce cut by more than half to 95 since jobs peaked at 225 in 2012. Improving the environment with acres of prairie is a plus, but placing greater resources toward reclaiming stripped land is part of an effort by Peabody -- the largest U.S. coal miner -- to reduce its $1.2 billion (£913.8 billion) liability for future environmental cleanup costs. The quicker Peabody can recreate native grass and sagebrush, the sooner it can cut costs, free up cash and make its mines more attractive to potential buyers. It can also help Peabody meet a target of emerging from bankruptcy by next April. "We're doing everything we can to reduce our liability to a minimum," said Phil Dinsmoor, Peabody director of environmental services in Wyoming's Powder River Basin, where Rawhide sits. Before Peabody can exit bankruptcy, it must first overcome a $1 billion dispute between creditors -- including some of Wall Street's most litigious investment funds -- over claims on the coal producer's assets. In addition to planting grass, Peabody is also accelerating applications to regulators seeking approval of the reclamation of roughly 8,000 acres of land at its 28,000 acre North Antelope Rochelle, a mine adjacent to national parkland 50 miles south of Rawhide that produces more coal every day than anywhere else in the world. If its application is approved, Peabody will be able to remove millions of dollars of liabilities from its books. The company declined to disclose the total amount by which it expects the accelerated cleanup efforts to reduce liabilities. Whatever the motivation, environmental groups said an expedited plan by Peabody to clean up pits and win regulatory blessings for the reclamation will bring more transparency to the status of the mines, which is good news. "We'll finally be able to see whether they are meeting environmental standards," said Dan Cohn of the Western Organization Resource Councils, a grassroots group that watches over coal mining. CLEANUP REQUIREMENTS Under U.S. law, mine operators are required to clean up pits and restore vegetation after minerals have been extracted. Like other coal companies, Peabody has participated in a federal programme called "self-bonding" that exempts healthy companies from posting collateral to cover environmental liabilities, essentially guaranteeing them with little more than a promise. With roughly half of U.S. coal companies in bankruptcy due in part to low natural gas prices and falling demand in China, state and federal regulators are questioning whether the companies can make good on their pledges. Both the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate have introduced bills to ban self-bonding, and uncertainty about whether the programme will continue has complicated some plans to restructure troubled companies. There were $3.9 billion of self-bonds across the United States as of June 1, including $2.2 billion in the hands of bankrupt coal miners, according to federal mining regulator Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation Enforcement (OSMRE). This month, U.S. coal miner Alpha Natural Resources agreed to replace its self-bonds in Wyoming with other guarantees as part of a complex deal to exit bankruptcy, though it will continue to cover reclamation at former mine sites in West Virginia with self-bonds. Compared to other bankrupt miners, Peabody has the most self-bonds at $1.2 billion followed by the second largest U.S. coal producer Arch Coal with $458 million. Arch declined to comment on whether it was taking similar steps to Peabody. In order for land to be certified as reclaimed, state regulators must sign off on a three-stage cleanup. A percentage of reclamation bonds is released after each stage and the full amount is returned once native grass and waterways have been restored, a process that takes about 10 years in Wyoming. This year, Peabody expects to recreate hills at 400 acres of former coal pits at Rawhide, three times the annual average between 2013 and 2015, and plant seeds at over a third of that land to return habitats to the area's grazing cattle and pronghorn antelope. "When we walk out of here, we don't want anyone to know we were here," said Peabody's Dinsmoor. (Reporting by Tracy Rucinski; Editing by Amy Stevens and Edward Tobin)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News