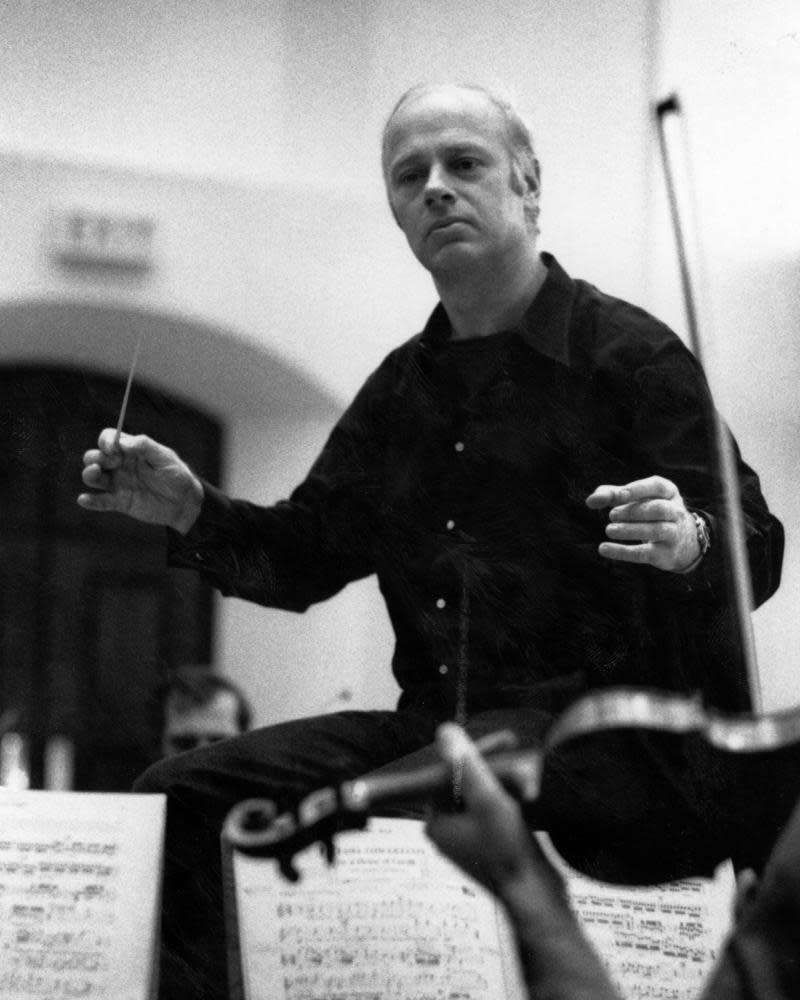

Bernard Haitink obituary

In the autumn of 1998, Bernard Haitink, who has died aged 92, conducted a magisterial account of Wagner’s Ring cycle at the Royal Albert Hall, London. The Royal Opera House at Covent Garden was closed, its board and management in disarray; there was serious doubt about the future of both the opera and ballet companies, and it was known that Haitink was considering resigning from the music directorship. It later emerged that he had indeed offered his resignation but had withdrawn it, chiefly out of loyalty to his performing colleagues.

The orchestra, which played gloriously throughout the long crisis, seemed the only stable element left, and at the end of Götterdämmerung it received, with its conductor, a tumultuous ovation. Haitink, a man of few words, raised a hand and said, “Thank you. You all know the situation. It’s desperate. Please help us.” It was a touching plea that may have reminded the wider world that while sound planning and bookkeeping are indispensable, it is the music-making that matters most.

Haitink’s six decades of performing at the highest level began in his native Netherlands in 1959, after the death of Eduard van Beinum, conductor of what is now the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam. The young Haitink succeeded him – initially in tandem with the German conductor Eugen Jochum. From 1963 he held the post in his own right, and did so with distinction for a quarter century. Notable performances included the Dutch premiere of Britten’s War Requiem in 1964, with the composer himself conducting the additional chamber orchestra, and with the Russian soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and British tenor Peter Pears as soloists.

Jochum’s departure enabled Haitink to perform more of the German repertoire, and within a few years he had embarked on Bruckner and Mahler cycle recordings. It was probably these works that appealed to the London Philharmonic Orchestra, which appointed him principal conductor in 1967. By this time he had conducted in New York and Washington with the Concertgebouw, had guested in Munich and Los Angeles, and had appeared at the Edinburgh festival and the Proms, for whose audience and ambience he was to develop an especially soft spot.

His first opera was Don Giovanni, in a modest Netherlands Opera production with which he was very dissatisfied. But opera was to become one of his finest achievements. In 1986, he told me on the BBC World Service: “The theatre has given me something I needed badly … it has enriched my life incredibly.” And there is no doubt that his sense of the dramatic was greatly enhanced by his experience of opera. Though he thought his performance of Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail at Glyndebourne in 1972 “too symphonic”, it was well liked by the press and public, and he returned for Die Zauberflöte the following year.

Glyndebourne’s antennae were never more sensitive: Haitink had in him the makings of a great opera conductor – though, characteristically, he was not so sure. At Glyndebourne, between 1975, when he conducted Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress, and 1978, when he took over as music director, he added Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande to his as yet modest repertoire. There followed operas including Mozart’s Così Fan Tutte, Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier, Bizet’s Carmen, Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra and Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The director Peter Hall remarked that Haitink was the ideal collaborator because “he leaves his ego outside the rehearsal room”.

Though the LPO was resident at Glyndebourne, Haitink’s relationship with its management, after a long and happy honeymoon, deteriorated sharply, and he resigned as the orchestra’s artistic director in 1978. He had done a lot for the orchestra, but most of his recordings (including a Brahms cycle) had been made with the Concertgebouw. He left the LPO without regrets: he was in regular demand by many of the world’s great orchestras, among them the Vienna Philharmonic and the Boston Symphony, whose chief guest conductor he became in 1995.

In 1977 Haitink had made his debut at the Royal Opera House with Don Giovanni, and later that year he triumphed in Wagner’s Lohengrin. He returned with Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera in 1981 and, two years later, it was announced that he would take up the music directorship at Covent Garden in 1987, with the departure after 16 years of Sir Colin Davis. Thus the new music director was the man who had once said: “I don’t think I have the temperament for running an opera house … you need about five extra skins.”

By no means thick-skinned, Haitink presided at the Royal Opera House by pure artistry. He detested musical politics and did not court personal publicity. It was really only when he was in the pit that the public was aware of his authority, and there his contribution was awe-inspiring. The range of his mastery of the established repertory – of Mozart, Verdi, Strauss, Janáček and, above all, Wagner – was combined with a commitment to 20th-century music – including Britten’s Peter Grimes and Tippett’s The Midsummer Marriage.

His concert work diminished, but he continued to appear at the Proms, where he had been a popular artist since 1966. The Promenaders adored him and he responded, from time to time, with some jokey badinage of the kind traditional in that unusual forum. But his Proms repertoire was serious: Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler were recurrent. Occasional were Dvořák, Tchaikovsky, Debussy, Stravinsky (notably The Rite of Spring) and Shostakovich.

British music was represented by Elgar (Haitink recorded both his symphonies, as he did Walton’s First and all nine of Vaughan Williams’), by Britten’s Spring Symphony and War Requiem, and by Alexander Goehr’s Metamorphosis/Dance. Specially memorable were a concert performance of Verdi’s Don Carlos by the ROH (1996) and Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, with which he opened the following year’s Proms, conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus and BBC Singers. Later in the same season he appeared with the European Union Youth Orchestra, whose music director he had become in 1994, when it was known as the European Community Orchestra, succeeding Claudio Abbado. In everything he did, he demonstrated a powerful and lucid control of large-scale forms, whether in the architecture of Bruckner’s symphonies or in the dramatic complexities of middle-to-late Verdi.

Though he made innumerable recordings with the Concertgebouw, he resigned in 1988 because of management changes and funding problems. “When he left, it was like when a marriage breaks up,” the flautist Rien de Reede said. For a while relations were strained, but 10 years later he was appointed conductor laureate, an honour he warmly appreciated. “Now he is St Bernard in Holland,” said De Reede. “His 70th birthday was a big thing, and when he comes back it is like when the Dutch swimmers at the Olympics come back with their gold medals.”

Born in Amsterdam, Bernard was the son of Anna (nee Verschaffelt), who worked for the French language institution Alliance Française, and Willem Haitink, a civil servant who was to become director of the Netherland electricity board. A shy child, during his early teenage years he experienced German occupation. His father was imprisoned by the Nazis for more than three months; that his maternal grandmother was Jewish was not discovered. Conditions were severe and food was scarce.

The boy tuned in – illicitly – to radio broadcasts of the Proms, listening to the conductors Henry Wood and Adrian Boult, and attended concerts by the Concertgebouw Orchestra under Willem Mengelberg, its conductor for half a century. He unearthed some miniature scores and began to follow them, and entered the Amsterdam Conservatoire, where he learned the violin.

In 1948 he met Boult (whom he later described as “really great”) and, in the same year, at the Edinburgh festival, persuaded the promoter Ian Hunter, who later became his agent, to let him into Rafael Kubelík’s rehearsals of Don Giovanni. Then, at Salzburg, he heard Wilhelm Furtwängler. He began to feel that conducting was his true metier – but military service intervened, and it was not until 1953, at a Netherlands Radio conducting course, that he began to attract attention.

An appointment as conductor with the network enabled him to acquire some repertoire, and his big chance came when the Concertgebouw Orchestra invited him to stand in for an ailing Carlo Maria Giulini, who had been engaged for the Cherubini Requiem, a work with which Haitink was familiar. The following season, 1957-58, he had seven concerts with the Concertgebouw, cementing their association.

The difficult period he went through with the ROH four decades later came to an end when Covent Garden reopened in December 1999, after more than two years’ building work. Haitink’s last three years as its music director not only saw a remarkable revival in the company’s fortunes, but also a further enrichment of his own gifts. When, in April 2002, he gave his last, towering performance of Tristan und Isolde, what the conductor Jane Glover described as his “radiant integrity” was rewarded with an explosive ovation and an avalanche of flowers. A similar reception greeted him at the two final galas in July, when he chose to conduct Act II of Le Nozze di Figaro, the King’s study scene from Don Carlos, and the closing scene of Die Meistersinger.

Appointed honorary KBE in 1977 and CH in 2002, Haitink remained a citizen of the Netherlands and retained his distinctive Dutch accent. But he was at home in Britain, especially at Glyndebourne, and with the British, whose sense of humour he shared.

Orchestral musicians admired his authority and, because he treated them as colleagues rather than minions, gave him their willing collaboration. His steadily growing stature as an interpretative artist made him a welcome guest worldwide. He became principal conductor of the Dresden Staatskapelle (2002–04), one of five great orchestras – with the Concertgebouw, the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonics and the London Symphony Orchestra – that he conducted in unforgettably eloquent concerts at the Barbican, London, in his 75th year. During 2006 he recorded, for LSO Live, a magnificent Beethoven cycle at the Barbican, and embarked on a four-year contract as principal conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In 2008 he started on a further association, with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe: “With the COE, I feel I am not a conductor any more. I feel like a musician who can make music with them.”

The following year, when he turned 80, one of the highlights came with the LSO: his Mahler Ninth at the Proms, a performance that, in the words of one critic, “held 5,000 people mesmerised” for its nobility, its immaculate execution and unbearable poignancy. In 2013 came Shostakovich, the symphonies nos 4 and 15, with the LSO; he had met the composer in 1975, and considered him “too great to be miserable”. His final two retirement concerts, in September 2019, were with the Vienna Philharmonic at the Proms and in Lucerne.

The diffident young violinist had risen to a rare eminence, leaving far behind those occasions when, as a younger and less confident musician, he had sometimes sounded pedestrian.

Narcissism was alien to his nature and he never resorted to pushy or inflated publicity. “I don’t like to listen to my recordings,” he told me. And when I questioned him about his emotions and the part they played in his conducting, he had the perfect – and perfectly characteristic – formula: “Think with the heart. Feel with the brain.” He included some biographical reflections in the book Dirigieren Ist ein Rätsel (Conducting Is a Mystery, 2019), written with the journalists Peter Hagmann and Erich Singer.

Haitink married four times, in each case to a musician. In 1956 he married his first wife, Marjolein Snijder, and they had two sons and three daughters. His fourth wife was Patricia Bloomfield, a barrister and former viola player at the ROH, whom he married in 1994. She and his children survive him.

• Bernard Johan Herman Haitink, conductor, born 4 March 1929; died 21 October 2021

• Robert Ponsonby died in 2019

Yahoo News

Yahoo News