The Best in Art, From Musée d’Orsay’s Blockbuster ‘Manet/Degas’ Show to a Mark Rothko Retrospective

The Big Idea: An Art World Divided

Before October 7, the contemporary-art world tended to be seen as a reliably liberal bloc, with shared values around issues of social justice including race, gender, and reproductive rights. But Hamas’s attack on Israel that day and Israel’s subsequent invasion of Gaza have divided artists, gallerists, curators, and other art professionals in an unprecedented manner.

Across the art world, people traded accusations of anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, and censorship. Pro-Palestinian protests erupted at numerous institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Talks were disrupted; artists pulled works from shows. In one case, a group of Jewish anti-Zionist artists withdrew their pieces from San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum, in part to protest funding from the Israeli government and pro-Zionist foundations. Another museum in that city, the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, closed for several weeks after nine of the 30 artists in its triennial spray-painted pro-Palestinian messages onto their own works and demanded that any supporters of Zionism be removed from the board. The interim CEO, who is Jewish, resigned, citing fears for her safety.

More from Robb Report

Estée Lauder's Former Vacation Home in Cannes Just Listed for $8.7 Million

How Heirloom Grains Are Bringing Unique New Flavors to Whiskey

Private institutions have also become targets. New York’s Neue Galerie, founded by Ronald Lauder, president of the World Jewish Congress, was splashed with red paint, as was Pace Gallery, which was tagged with slogans such as “Free Gaza.” Its opening reception for an exhibition by Israeli artist Michal Rovner was disrupted by protesters. A group of small galleries on the Lower East Side were plastered with posters printed with slogans such as “Stop selling to Zionists.”

On the flip side, museums have canceled or delayed exhibitions by artists who have been critical of Israel. Indiana University’s Eskenazi Museum of Art called off the respected Palestinian American abstract painter Samia Halaby’s retrospective at nearly the last minute after she labeled Israel’s bombings genocide. The prominent philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler withdrew from a lecture series at the Centre Pompidou after detractors accused her of anti-Semitism for describing the October 7 attacks as “an act of armed resistance” rather than as terrorism.

The turmoil has reached far beyond the U.S. Germany has been convulsed with uncharacteristic criticism of its longtime support of Israel, and Ruth Patir, the artist representing Israel at the Venice Biennale, has refused to open her country’s pavilion until there is an agreement for both a ceasefire and the return of Israeli hostages. The discord is loud and pronounced, the pain searing. The question left for those from every corner to resolve: How will the art world heal itself?

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Click here to read the full article.

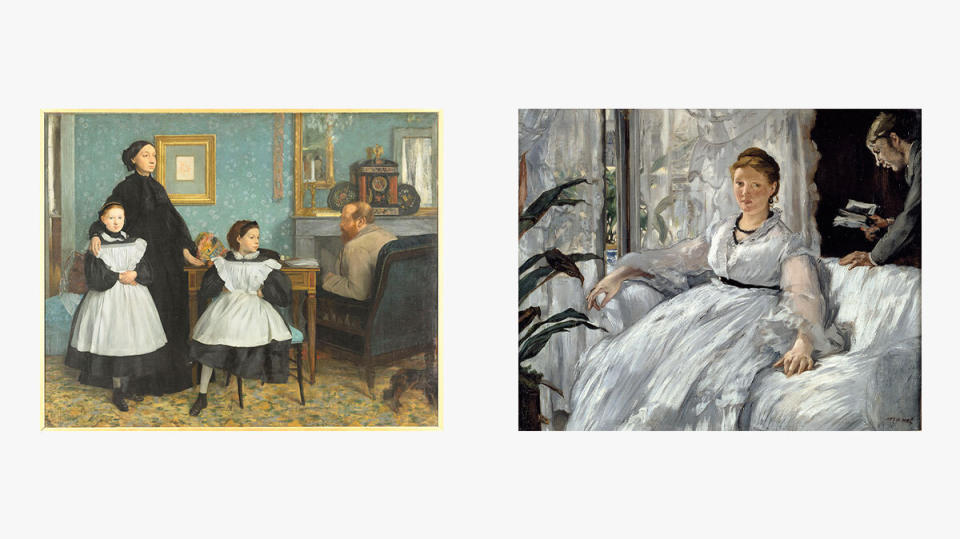

Blockbuster: ‘Manet/Degas’, Musée d’Orsay

From left to right: Edgar Degas, Portrait de famille, between 1858 and 1869, oil on canvas; Edouard Manet, La Lecture, between 1848 and 1883, oil on canvas

Even on a normal day, the Musée d’Orsay’s trove of works by Manet and Degas is an embarrassment of riches. (It was telling to stroll through the museum’s galleries and take in the paintings the curators didn’t bother to include in the special exhibition, among them Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe.) But more than its jaw-dropping assembly of masterpieces—here Manet’s The Balcony, there Degas’s A Cotton Office in New Orleans—this deep dive into two giants of the 19th century offered an intimate view of a close friendship and subsequent rift that would help shape the history of art.

The pair met at the Louvre (admiring a Velázquez, no less) and struck up the kind of rapport that only peers can. On parallel paths, they painted modern life: bourgeois families, outings at the beach, millinery shops, drunks—and most consequently, female nudes. The source of their falling-out remains a mystery, though the fact that Manet slashed a portrait of himself and his wife that Degas had given him leaves tantalizing room for speculation. But if any question remains regarding Degas’s opinion of his rival, consider his actions after Manet’s premature death at age 51 in 1883: He became one of Manet’s most active collectors, eventually acquiring almost 80 works.

In the fall, Manet/Degas alighted at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, giving stateside viewers an unprecedented chance to see Manet’s audacious Olympia—arguably the canvas that ushered in modernism—in the flesh, so to speak.

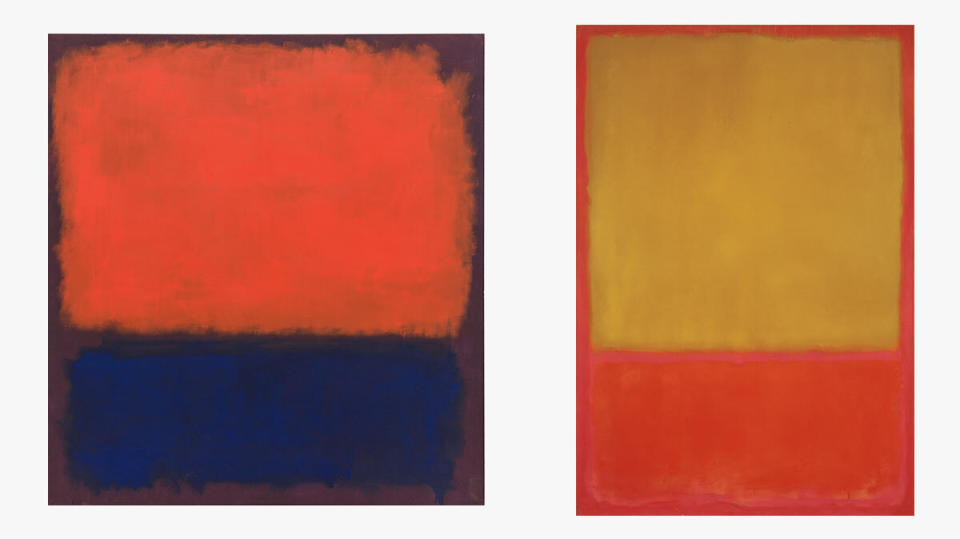

Retrospective: ‘Mark Rothko’, Fondation Louis Vuitton

Mark Rothko, The Ochre (Ochre, Red on Red), 1954, and No. 14, 1960, both oil on canvas.

This major Rothko retrospective was well worth what was clearly a heavy lift on the part of the Parisian museum: Besotted critics rightly called it “spellbinding,” “monumental,” and “stunning.” Beginning with his early, representational paintings of the 1930s, continuing through his flirtation with surrealism in the 1940s, and climaxing with his mature, abstract expressionist period, Fondation Louis Vuitton’s presentation captured this singular artist’s creative development in 115 works displayed over four floors.

Most viewers, no doubt, came to see his luminous canvases awash in gently stacked swaths of reds and blues, yellows and oranges, pinks and purples and blacks—the essential pieces one could easily get lost in. The museum succeeded in borrowing nine Rothkos donated to London’s Tate Gallery by the artist and normally displayed in a special room there; the deep-red paintings were originally planned for the Four Seasons restaurant in Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building in Manhattan, but Rothko reneged on the commission. New York’s loss, London’s gain.

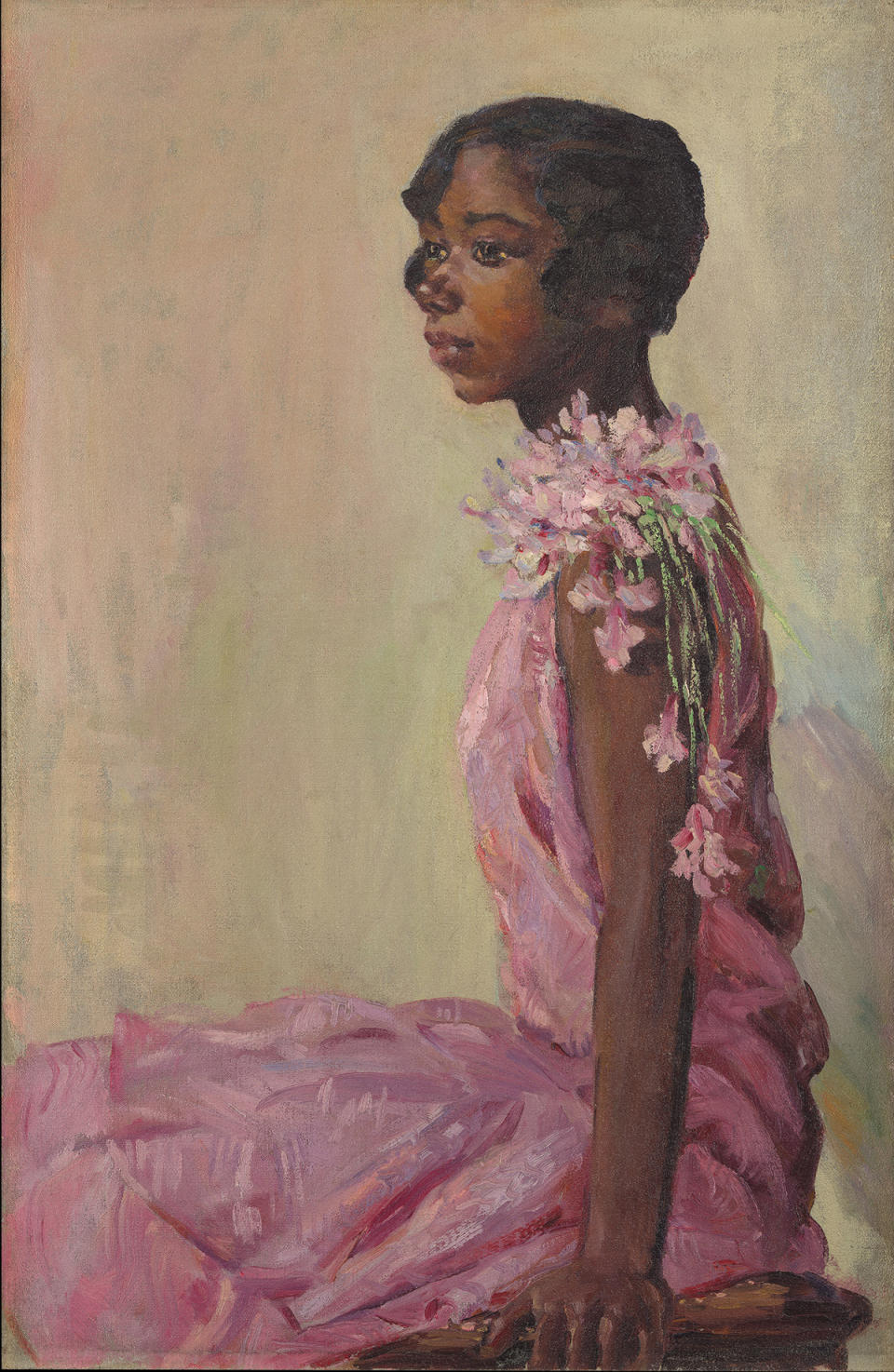

Historical Exhibition: ‘The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism’, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Laura Wheeler Waring, Girl in pink dress, oil on canvas, ca. 1927.

The flowering of music, literature, and fine art from the 1920s to the ’40s in New York and other American cities during the early days of the Great Migration is well-documented, with Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, Langston Hughes, Nella Larsen, Archibald Motley, and Laura Wheeler Waring among the scores of talents who defined a generation with their inventive approaches to Black self-expression. With this show, the Met has finally given the era its due: Curator Denise Murrell advances the narrative by making a strong case for the artists as major players in—not just acolytes of—the modern-art movement that was sweeping the globe.

You have until July 28 to catch Motley’s expressionist canvases capturing Black joy, Waring’s elegant portraits, and William H. Johnson’s bright, flattened depictions of vibrant urban life, among the more than 160 paintings, sculptures, drawings, photographs, and archival materials on display.

Survey: Simone Leigh, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston

Simone Leigh, Cupboard, 2022, bronze and gold, and Sentinel IV, 2020, bronze, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston.

In 2022 Simone Leigh became the first Black woman to represent the U.S. at the Venice Biennale; she also walked away with the prestigious Golden Lion for her contributions to the main group exhibition. Last year, fresh off that acclaimed outing, Leigh brought her strikingly original sculptures celebrating Black women—and the art and architecture of Africa and its diaspora—to the ICA.

Leigh creates monumental figures in clay and bronze, often absent eyes but with exaggerated hips and lower bodies covered in raffia, resembling thatched dwellings.

The work confronts racism in nondidactic but blistering ways, with pieces that allude

to “mammy” stereotypes in the American South, souvenir photographs of Black female laborers, and the enslaved man Ota Benga, who was exhibited in a cage at the Bronx Zoo in 1906 and later died by suicide.

If you missed the ICA’s presentation, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the California African American Museum are now jointly hosting the survey, which will be on view through January 20.

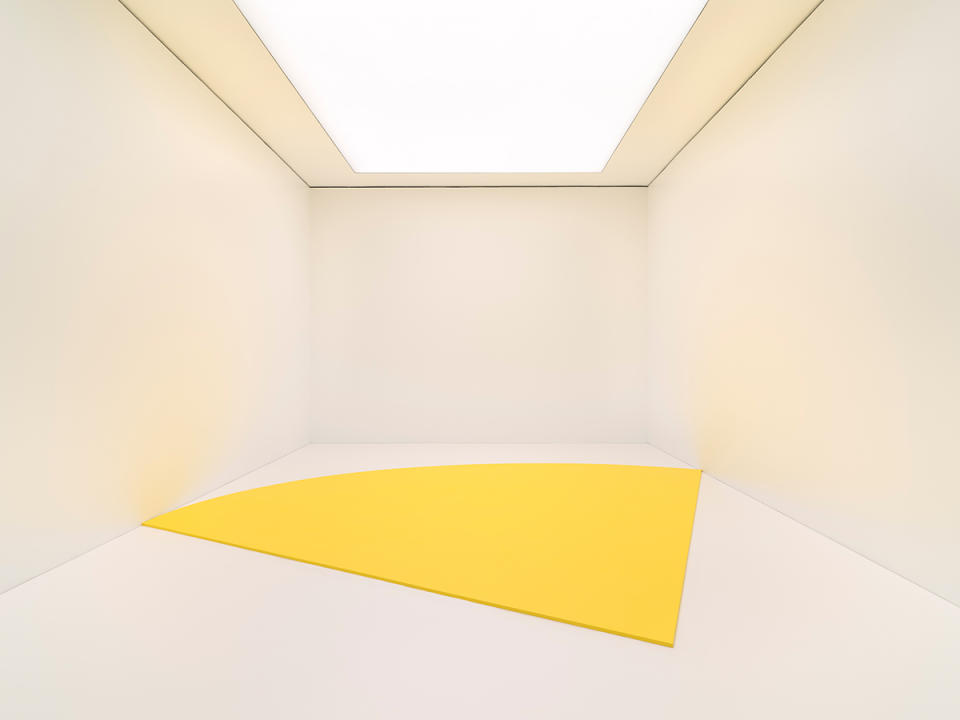

Anniversary Show: ‘Ellsworth Kelly at 100’, Glenstone

Ellsworth Kelly, Yellow Curve, 1990, acrylic on canvas on wood

Ellsworth Kelly, the difficult-to-categorize artist famed for his large, shaped canvases painted in brilliant monochromes, would have turned 100 last year. To mark the milestone, Glenstone, the private museum exquisitely situated on the sprawling Maryland estate of its founders, Mitch Rales and Emily Wei Rales, put on quite the centenary celebration.

The couple, longtime friends and collectors of the artist, who died in 2015, filled the galleries with Kelly’s curved paintings and totemic sculptures as well as his sublime plant drawings, inspired by daily walks in the countryside around his house in Spencertown, N.Y. Also on view were some of his less-exhibited black-and-white photographs—the slant of a roof, the slope of a snow-covered hill, a signpost and its shadow, a half-boarded window—which offer an intriguing glimpse into how he translated the world around him into his sharply defined, geometric abstractions.

The retrospective, Glenstone’s first traveling exhibition, is on view at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris through September 9.

Book: ‘The Work of Art: How Something Comes From Nothing’ by Adam Moss

After the revered editor Adam Moss stepped down from New York magazine in 2019 following a 40-year career in journalism, he tried his hand at painting. Luckily for the rest of us, he wasn’t very good at it. His struggles led him to write The Work of Art, which became an instant bestseller when it was published this spring. The title’s nuance is a tip-off to what sets this book apart: It’s an ode to the hard labor (both physical and mental) that goes into making art.

Moss set about interviewing more than 40 acclaimed creators of all stripes—visual artists, poets, composers, novelists, designers, filmmakers, playwrights, chefs, and even The New York Times crossword guru Will Shortz—to tease out their processes by focusing in on a specific project by each. Kara Walker recounts the development of her monumental sphinx-mammy installation, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby; George Saunders talks about Lincoln in the Bardo. And no less a luminary than Stephen Sondheim treats his enraptured audience (self-proclaimed fanboy Moss but also, by extension, us) to an account of how he completely transformed “The Wedding Is Off,” a comic song that just wasn’t working, into the showstopping “Getting Married Today” for the musical Company.

Group Exhibition: ‘Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than The Real Thing’, Whitney Museum of American Art

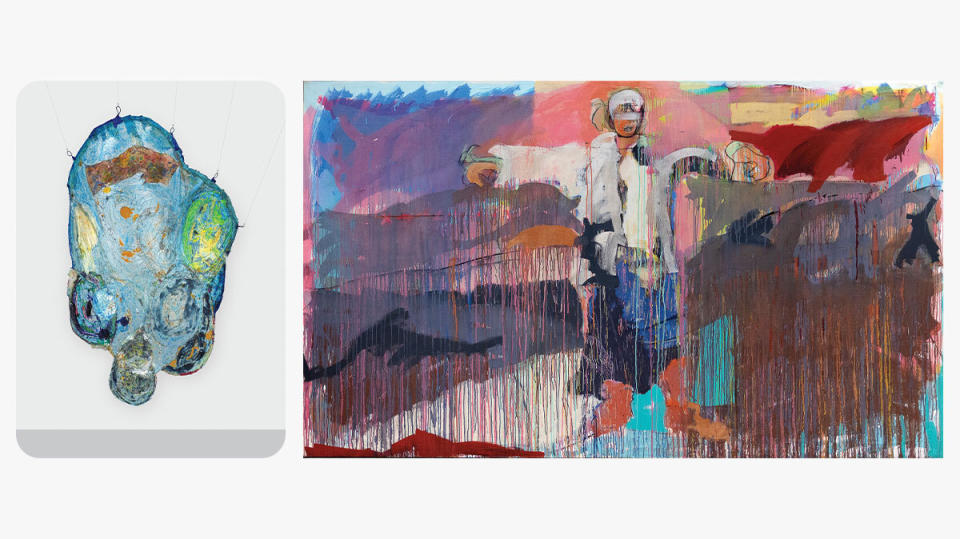

From left to right: Suzanne Jackson, Rag-to-Wobble, 2020, acrylic, cotton paint cloth, and vintage dress hangers; Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Self-Portrait—She Now Calls Herself Sahara, ca. 1990s, acrylic on canvas.

For this biannual exercise (the museum’s 81st) in showcasing art that defines the scene today, lead curators Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli recruited a broad array of artists representing diverse ethnicities, geographies, genders, and sexualities. But what’s particularly refreshing is that some of the most compelling work comes courtesy of octogenarian women, among them two Black artists. Mary Lovelace O’Neal’s large abstract paintings, such as Blue Whale a.k.a. #12 (from the “Whales Fucking” series), command the viewer’s attention. Suzanne Jackson’s canvas-free pieces, made from layers of acrylic paint, hang from above like brilliantly colored skins, or two-dimensional two-sided sculptures to be slowly circled.

Other highlights among the 71 artists and collectives include Jes Fan’s eerily beautiful sculptures based on CAT scans of his body; Lotus L. Kang’s installation In Cascades, a forest of dangling, monumental photographic films that she has exposed to light; and ektor garcia’s delicately intricate crochet sculptures. The Biennial is on view through August 11, but if you can’t make it to New York by then, the film program is available online.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News