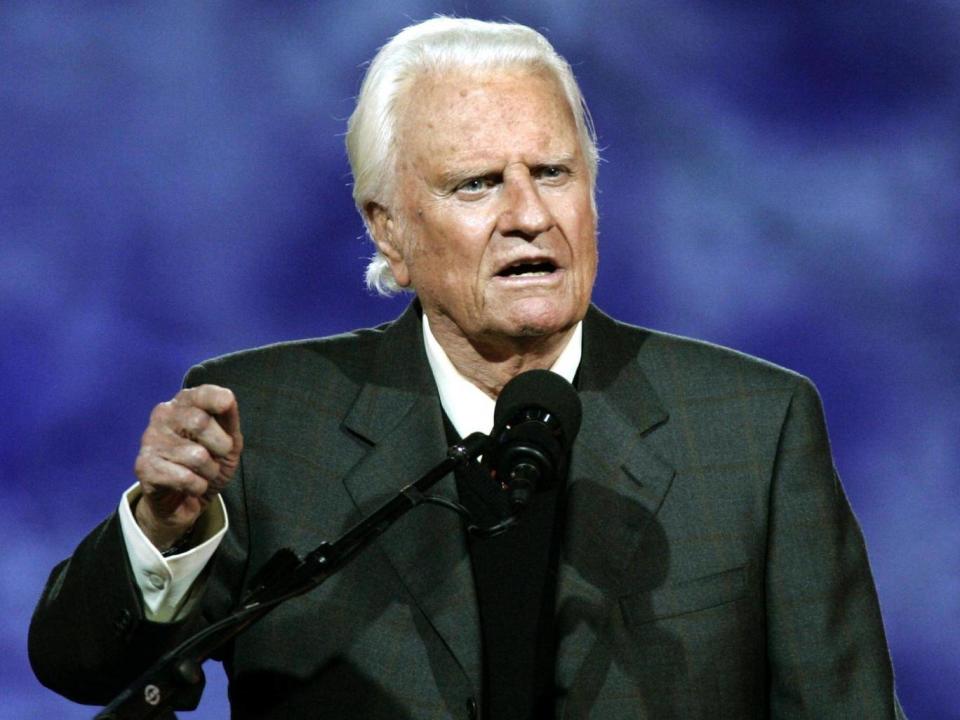

Billy Graham: American evangelist preacher who was a friend to presidents and the Queen

In terms of sheer arithmetic, Billy Graham was the most successful evangelist the world has known, a man who preached the Gospel to more people than any other person in history.

For countless millions both inside and outside the US he became a standard bearer, not just of American Protestantism, but of America itself. His tall, gaunt frame, his granite jaw and flowing mane projected the very image of a modern prophet. The Billy Graham Crusades for Christ created a formula that proved as successful in its way as McDonald’s hamburgers or Kentucky Fried Chicken. Backstage organisers and public-relations managers prepared the ground for months, ensuring that the stadiums were filled to capacity.

The chosen hymns – old favourites such as “Bless the Lord, O My Soul”, “Amazing Grace” and “When We All Get to Heaven” – reflected a broad, user-friendly approach: nothing too devotional that might embarrass newcomers or non-believers. Guest singers like Cliff Richard and Johnny Cash imparted a country-and-western flavour, while Graham’s sermons, delivered in rambling, conversational style punctuated by clenched fists, pointing fingers and hands thumping the Bible like thunderbolts, carried all the conviction of Charlton Heston playing Moses.

The sermons on the familiar, all-embracing themes of sin (especially sexual sin) and redemption, were timed to the second to guarantee rapid editing so the videotapes could be distributed with the minimum delay.

Every service reached the same predictable climax: the “invitation” to the audience to make their “decisions” for Christ – whether for the first time, or to reinsure themselves after a period of “backsliding” when Christ’s “warranty” might be thought to have lapsed. The faithful, or newly converted, would then line up to make their dedication, and receive a blessing from the great evangelist himself.

The size of the harvest of souls wrought by these performances is widely disputed. Graham’s policy was to encourage converts or “enquirers” to join or return to their local churches, leaving it to the clergy to follow them up. Since the attitude of local clergy tended to vary from warm endorsement to outright hostility, the follow-up process was uneven and variable in its results. One academic study concluded that less than a third of enquirers actually went on to join local churches.

In any case the proportion of those in the audience who took up the “invitation” was often quite small. His original mentor, Bob Jones II, told Graham “your converts don’t last” – a claim that was often repeated over the years. Graham’s supporters would argue that gains or losses in terms of individual happiness or moral good cannot be quantified statistically.

Born in the South Carolina Bible Belt into a modestly prosperous farming family, Graham was brought up with a strict literalistic view of biblical truth.

Heaven was a physical place, as real as London or Chicago, somewhere near the North Star, measuring 1,600 cubic miles; among other celebrities, he once told an audience, he expected to find Elvis Presley there.

Like most American fundamentalists he held the pre-millennialist view that Christ would return before establishing the 1,000-year reign of peace on earth.

Pre-millennialists tend to be pessimistic and deeply conservative, since there is no point in improving a sinful world that will soon be destroyed.

As the “End Times” approach, with all the portents of famine, pestilence and war foretold in the Book of Revelation, the Christian’s duty is to save individuals, not society – to get them into the lifeboat, to use a favourite metaphor. While socially regressive, the pre-millennialist view that Christ’s return is imminent, when the “saved” will the “raptured” into the air and all others will be left behind, lends urgency to evangelical efforts.

Graham received his early training at Bob Jones College in North Carolina and the Florida Bible Institute, and although he found both regimes too restrictive and scholastic, he never formally abandoned the pre-millenialist doctrines they taught. An indifferent scholar, Graham poured all his energies into the art of preaching, sometimes memorising whole texts of sermons culled from printed books. He completed his education at Wheaton College, Illinois, majoring in anthropology – a discipline that apparently taught him that all people everywhere were essentially alike and equally susceptible to the Gospel.

After an attack of mumps prevented him joining the army as a chaplain at the end of the Second World War, he joined Youth for Christ (YFC), an evangelical organisation which gave him the opportunity and means to preach at high schools and colleges, civic clubs and business groups throughout the union. During 1945, with funds provided by the organisation’s wealthy backers, he visited 47 states, logging some 135,000 miles. United Airlines recognised him as its most frequent civilian flyer. His talents as a publicist were already apparent.

Along with usherettes, youth choirs and smooth melodies played on a “consecrated saxophone”, YFC rallies were warmed up by a horse named after General MacArthur who knelt before the cross, and tapped his hoof 12 times when asked how many apostles there were.

However it was politics, rather than gimmickry, that brought Graham nationwide attention. Like other pre-millennialists he identified the Soviet Union as the antichrist: “Communism is not only an economic interpretation of life,” he told an audience in Los Angeles.

“Communism is a religion that is inspired, directed and motivated by the Devil himself who has declared war against Almighty God.”

The fire of that war, he warned them, would fall directly upon their city “because the fifth columnists, called communists, are more rampant in Los Angeles than any other city in America”. Such tirades endeared him to the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst who ordered his editors to “puff Graham”. The coverage thus assured was reinforced in 1950 when Graham entered major-league broadcasting. Within weeks of its launch, his radio show, The Hour of Decision had attracted the largest audience ever recorded for a religious broadcast, spreading to 1,000 radio stations in the US. A television version, on the fledgling ABC network, commenced the following year.

Graham consolidated his success by assiduously courting political power. Although President Harry Truman reacted coolly towards his overtures – viewing him as a self-seeking “counterfeit” bent on publicity – Eisenhower recognised his potential political value, as did Vice President Richard Nixon.

In the 1960 presidential race, Graham backed Nixon against John F Kennedy, refusing to sign the Catholic senator’s pledge not to bring religion into the campaign.

Nevertheless he prudently avoided saying anything that would alienate Kennedy. He later declared that the new President would promote a better understanding between Protestant and Catholic churches. By 1964 Graham’s influence was such that President Johnson found it politic to befriend him, and actually attended a “Crusade for Christ” in the Houston Astrodome, the first President go so far.

Graham rewarded Johnson by lambasting the Vietnam war protesters demonstrating outside the stadium, comparing them unfavourably to the good Christian youths within. Nixon’s victory in 1967 delighted Graham: his friend, whom he regarded as “deeply religious”, would go down as “the greatest President in American history”. When the Watergate scandal broke, Graham at first refused to accept that Nixon’s “moral and ethical principles would allow him to do anything illegal”. The transcripts of the Watergate tapes exposing the President’s cynicism proved personally shattering for the evangelist.

He may well have come to the conclusion that his other presidential “friends” had also been using him for their own ends, finding that it improved their images wonderfully to be associated with the America’s most famous professional Christian. After Watergate, Graham was more cautious in his dealings with the White House. Though close to Ronald Reagan, he refused to endorse him publicly.

Graham sought to justify his political opportunism with the words of St Paul. “I have been all things to all sorts of men that by every possible means I might win some of them to God,” he said. When charged with his failure to confront presidential wrongdoing he would say: “I am not Nathan” – referring to the Old Testament prophet who called King David to account over his affair with Bathsheba.

His liberal critics, however, felt that his refusal to speak out against racism, Vietnam and other foreign policy excesses, his preference for ranting against the evils of sexual permissiveness while ignoring the death and destruction caused by military or institutional violence, smacked less of Paul – who after all, suffered imprisonment and martyrdom for his views – than Zedekiah, the false prophet favoured by Ahab, King of Israel, for telling him what he wanted to hear.

Although Graham accepted than men were created equal by God, he had preached before segregated audiences in the South, claiming that his purpose was “to proclaim the Gospel, not promote integration”. American liberals, notably Reinhold Niebuhr, the country’s foremost theologian, criticised his failure to take black suffering seriously. Graham’s lukewarm support for the civil rights movement does not seem to have been based on personal prejudice. It stemmed rather from his pre-millennialism and reluctance to countenance any breaking of the law. For him the ultimate obstacle facing the realisation of Martin Luther King’s “dream” was eschatological: only after Christ’s return would the “little white children of Alabama walk hand in hand with the little black children”.

The primacy Graham gave to law and order over the Christian conscience was manifested most clearly, and paradoxically, in the historic crusades he held in Russia and Eastern Europe during the 1980s. Despite his earlier condemnation of communist governments as agents of Satan, he agreed to refrain from all criticism in order to be allowed to preach. In Moscow, he went far beyond the requirements of diplomatic etiquette by quoting the 13th chapter of Romans, in which Christians are urged to obey the authorities.

When a Soviet demonstrator protesting at religious persecution was hauled away by plain-clothed police, Graham blandly told his audience that people in the United States were also liable to detention “if we catch them doing something wrong”. On a visit to Ceausescu’s Romania he stunned observers by congratulating the authorities for giving “full and generous freedom to all religious denominations”.

Given his preference for order over anarchy, it is hardly surprising that the Chinese authorities welcomed him to Beijing in 1988. Here he was able to explain to them that Christians made the most reliable and hard-working citizens: honest family people who did not gamble or drink away their pay or otherwise make trouble for the authorities.

As time went on Graham began to waver from the strict pre-millennialist belief that winning souls could be detached from addressing political and social evils. In the 1980s he became an increasingly passionate advocate of disarmament – an activity that would logically postpone, rather than hasten, Armageddon.

Abandoning his insistence on the futility of human action this side of the millennium, he began to address issues of social justice, and even to echo Catholic statements about “God’s preferential option for the poor”.

As the complex realities of the modern world became increasingly apparent, Graham and his organisation were forced to grapple with the thorny problems of religious and cultural pluralism. On abortion and homosexuality, two of the touchstones of fundamentalist orthodoxy, his less-than-absolutist position drew fire from ultra-conservatives. “I don’t get involved in the abortion thing,” he said in a 1994 interview. “I preach to unite people ... God loves the homosexual as much anyone else. I think homosexuality is a sin, but no greater than idolatry and adultery. In my judgment it’s not that big.”

Traditional evangelicals were equally annoyed by growing ecumenism, manifested in his admiration of the late Pope John Paul II as “the greatest religious leader of the modern world and one of the greatest moral and spiritual leaders of this century”. In the latter part of his career his tolerance appeared to stretch even beyond the boundaries of Christendom. God was “calling people out of the world for his name”, he told the television preacher Robert Schuller in 1994. “Whether they come from the Muslim world, or the Buddhist world, or the Christian world or the non-believing world, they are members of the body of Christ.”

The conferences of world evangelists Graham set up at Lausanne in 1974 and at Amsterdam in 1984 and 1986 grappled with the challenge facing evangelists in non-Western cultures. His recognition that evangelism and sociopolitical involvement are both part of Christian duty – that “faith without works is dead” – opened the door to a new, theological departure.

Like other fundamentalists who found that Jesus was taking an inordinate amount of time to return, Graham shifted towards the post-millennialist view that the Second Coming would only happen after humanity had put the world to rights. In his last years he struggled against disease – Parkinson’s, a broken pelvis and prostate cancer – with impressive fortitude, drawing inspiration from the example of the ailing Pope John Paul II. “I’m looking forward with great anticipation to going to heaven,” he told an interviewer on the eve of his final crusade in New York in June 2005, which was attended by 80,000 people.

Despite his immense popularity, the sincerity with which Graham held his more liberal views remains open to doubt. A private conversation, secretly taped by President Nixon which came to light in 2004, revealed a virulent streak of antisemitism that contrasted starkly with the bland, ecumenical approach of his public statements. The Jews, Graham told the President, were responsible for “all the pornography” washing over America through the “stranglehold” they held over the mass media. The same year Graham’s son and chosen spiritual heir, Franklin Graham, (George W Bush’s favourite preacher) infuriated American Muslims by reverting to the older (and probably more authentic) Graham spirit when he declared that the God of Islam is not the same God as the God of the Judeo-Christian faith. “It is a different God and I believe Islam is a very evil and wicked religion.”

Billy Graham was no intellectual: but the charm and force of his personality was such that he persuaded many who knew him (though not Harry Truman) that he believed, and practised, what he preached. He successfully avoided the sexual and financial temptations to which several prominent “televangelists” succumbed during the Eighties. His visits to Britain allowed him to strike up a friendship with the Queen.

His financial dealings, with prudent fundraising practices and properly audited accounts, were generally models of probity. Convinced that Satan would stop at nothing to trap him, he ordered his aides to screen his hotel bedrooms for possible female infiltrators, and took care never travel alone in a car with any woman other than his wife.

The deals he made with totalitarian governments were justifiable according to his lights. In the eyes of God any means were acceptable in bringing Christ to the unsaved. (Knowing that their room was often bugged in communist countries, he and his wife would read long passages from the Bible in the hope of converting the spooks.)

The message he preached, like that of the “circuit riders” on the old American frontier, was essentially personal: so long as the individual got himself right with God, the Almighty could be counted on to deal with everything else. In key respects his views accorded with the Big Brother communism he once so adamantly opposed. “From birth to grave,” he told one of his British audiences, “God has a TV camera focused on you, and every bad word is being taped.”

Billy Graham, American evangelist, born 7 November 1918, died 21 February 2018

Yahoo News

Yahoo News