Black Power: A British Story of Resistance review – a tortuous fight for justice

Steve McQueen’s film series Small Axe grew out of a desire to tell Britain’s stories of black resistance. So, too, does this complementary documentary (BBC Two), executive produced by McQueen, narrated by Daniel Kaluuya and directed by George Amponsah, whose credits include the 2015 feature documentary The Hard Stop, about the aftermath of Mark Duggan’s death at the hands of the Metropolitan police.

These means are necessary – to borrow a phrase – because so many stories remain overlooked and untold. Narrative cinema has a unique power but, as conversations surrounding the Oscar-nominated Judas and the Black Messiah and The Trial of the Chicago 7 have demonstrated, Hollywood’s requirement that movies be palatable to a wide audience can trump historical accuracy, sometimes in troubling ways.

For many, the first surprise of British black power is that it existed – and not just in the hopeful imaginations of a few sixth-form revolutionaries with cool American cousins. This film describes a multifaceted movement for change that consisted of a variety of groups – the United Coloured People’s Association, the British Black Panthers, the Fasimbas, the Black Liberation Front and many more – all over the UK in the late 60s and early 70s. Interviews with key members and archive clips of others provide insight into what it was really like to be at those meetings, protests, court cases and house parties.

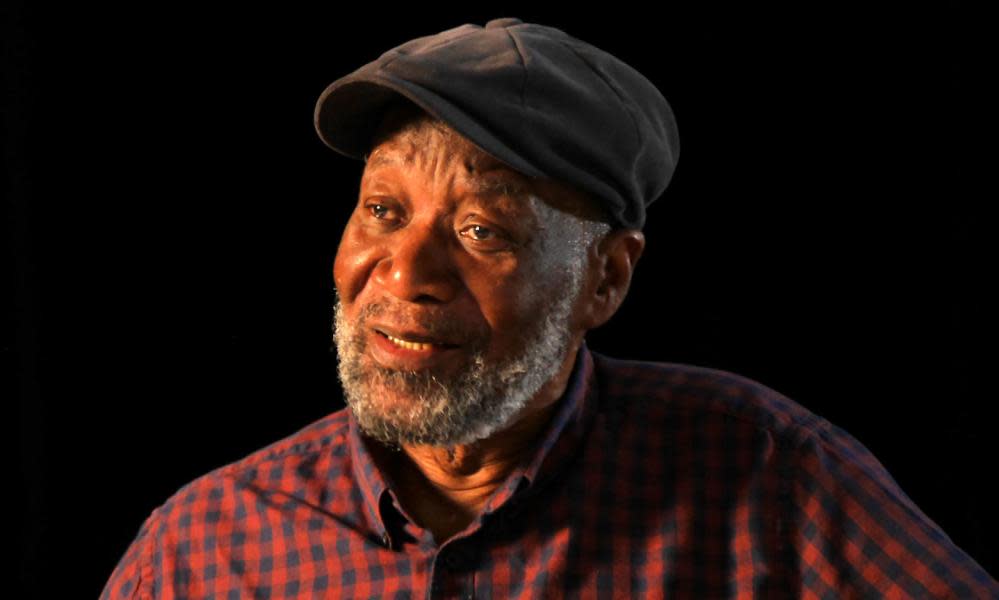

Most British schoolchildren study the US civil rights era, but this country has its own civil rights heroes: the brilliant legal mind and inspirational speaker Darcus Howe (who died in 2017); Altheia Jones-LeCointe, (played by Letitia Wright in McQueen’s film about the Mangrove Nine) whose incisive analyses remain on point; the exhilarating Speakers’ Corner presence Roy Sawh; the “fearless” south London community activist Olive Morris. Amponsah revives their reputations and honours their legacies with an editing device that takes us into the darkrooms of the black photographers Neil Kenlock and Charlie Phillips.

Any tendency towards fanzine-style fawning is kept in check by the inclusion of the movement’s most confusing, conflicted chapters. Candid, regretful accounts of the 1975 “Spaghetti House siege” reveal the extent to which revolutionary ideology is open to exploitation by dangerous elements. Among multiple, faltering attempts to explain how a petty crook and eventual murderer such as Michael “Michael X” de Freitas was able to hoodwink not only the establishment media, but also many good-faith, grassroots activists, it is Howe – speaking in 1998 – who seems to get closest: “I used to like to hear black people say things that were brave and bold, even if it didn’t make sense, because we were too quiet.”

Michael X featured recently in the Adam Curtis series Can’t Get You Out of My Head, but this documentary crams in much more relatively unfamiliar and unseen material – from the murder of Kelso Cochrane in 1959, through three ineffectual iterations of the Race Relations Act, right up to recent Black Lives Matter marches. The resultant sensation is one of struggling to keep up as history whooshes past, balanced by the equally strong impression that nothing ever changes.

Here, in 1964, is the Conservative candidate for Smethwick defending his notorious racist campaign and N-word sloganeering with the same “legitimate concerns” narrative that you hear from racist-appeasing politicians today. Here, in 1970, is an example of heavy-handed Met policing turning a peaceful protest into a violent confrontation.

The popular, long-running BBC drama Dixon of Dock Green ran until 1976, the same year that a new Race Relations Act once again exempted police from anti-racism legislation. While many of the people featured in this documentary have tragic personal experience of police corruption and brutality, the notion that friendly British bobbies could stray so far will remain difficult for many watching to accept.

This is why some of the most affecting moments in Amponsah’s film come not from activists, but from two former Met officers. One breaks down in tears while describing how he witnessed a colleague severely beating a black man in his cell: “I was kind of ashamed I was there, but I didn’t say anything … I didn’t have the courage to do that.” Another suggests with a waggish smile that, in fact, he was the victim: “Not believing that I would do a professional job? Y’know … who had the prejudice?”

Both of these examples are as useful to our understanding of how racism manifests itself in Britain as the most dramatic footage from a National Front rally.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News