‘The bravest person I ever knew’: Transgender computing pioneer Lynn Conway dies at 86

Lynn Conway, the tech pioneer and transgender trailblazer who helped revolutionize the microchip industry, has died at the age of 86.

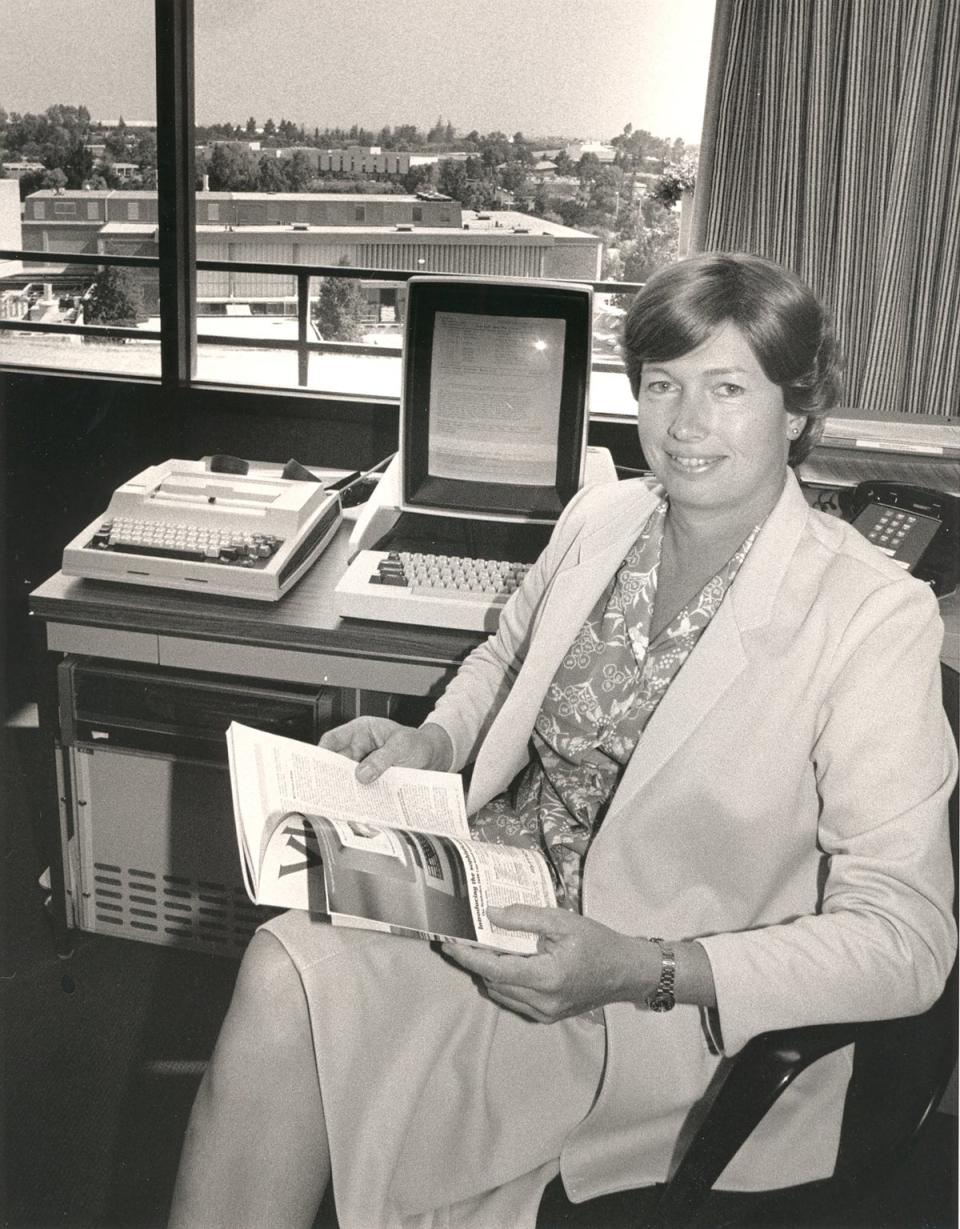

As a gifted computer architect in California’s Silicon Valley in the 1960s and 70s, Conway co-invented a new method of microchip design that now powers nearly every digital device in our lives, from smartphones to in-car electronics.

Yet, throughout those years, she was also secretly undergoing a gender transition that came with enormous personal and career costs, at a time when trans people were routinely targeted for violence and frequently denied the protection of the law.

After her retirement, she came out publicly and began sharing her story on her personal website, helping generations of younger trans people recognize themselves and learn about the process of transition.

“I think a lot of us [trans people] are living more interesting, more fun lives than most people. It’s our secret,” she told The Independent last year, in what is believed to be her final press interview.

“We are highly empowered – in ways that people may not understand – because of the joyfulness we feel in having been able to do what we do in spite of the difficulties, and find a place in society where we actually have joy in just living.”

Conway’s death was announced on Tuesday by the University of Michigan, where she served as a professor emerita, which said that she had passed away on June 9.

Michael Hiltzik, a columnist for The Los Angeles Times who had known her for 25 years, added that she died from a heart condition, and called her “the bravest person I ever knew.”

Conway was born in 1938 in White Plains, New York, growing up in a white middle-class world that she described as “haunted” by the violence and repression that lurked underneath its “appearance of normalcy”.’

After graduating from Columbia University in the early 60s, she moved to Silicon Valley to work on a secretive IBM supercomputer project.

She thrived on the work, but her personal life was falling apart under the pressure of her suppressed identity, and she finally resolved to undergo medical transitions.

Then IBM fired her after learning of her plans to transition, forcing her to restart her career almost from scratch in a new identity. It was, she recalled, very much like being a Cold War spy.

“You have to operate at a high level pretty quickly, or else you’ll get exposed, and then you’re a traitor to your whole institution,” she told The Independent. “But at the same time you have to be kind of affable, and not attract attention... can’t ever get angry, or show fear.”

Conway secured a job at Xerox’s PARC research lab, now famous for innovations such as the computer mouse and the digital desktop interface, where she began collaborating with California Institute of Technology professor Carver Mead to solve a thorny industry problem.

At the time, the number of components that could be squeezed into each microchip was increasing exponentially every year. But the resulting complexity was difficult to manage using traditional, bespoke methods of chip design, creating a bottleneck on actually exploiting this new power.

Conway and Mead’s innovation – known as “Very Large Scale Integration”, or VLSI – was to develop a set of rules for clustering components together in standardized blocks, like neighborhoods in a city, simple enough for even a novice engineer to follow.

“It was freedom of the silicon press,” Conway recalled, “where the designer, the creator, didn’t have to work inside the printing plant.”

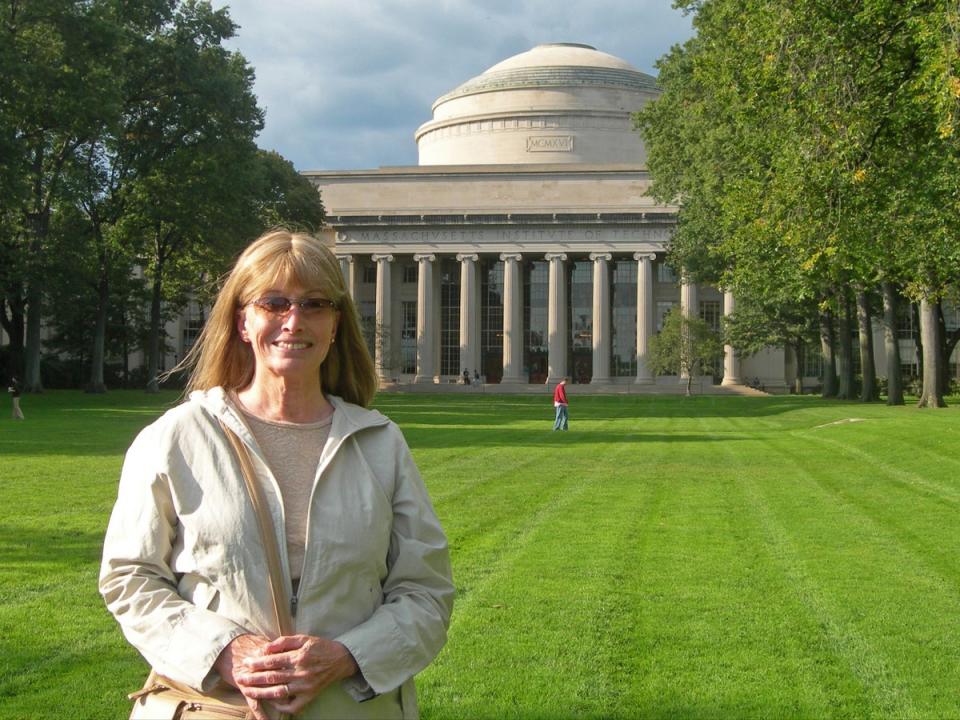

That work led to a post for Conway at the military research agency DARPA, and then a professorship at the University of Michigan.

She retired from active teaching in 1998, but continued her love of adventure sports such as rock climbing, motocross, and white water rafting.

In the years that followed, Conway came to feel that she had been unfairly left out of the computer industry’s popular history of her invention, and pushed aside in favor of her male collaborator.

“Mead probably thinks it was 80/20 him; most people, I think, in the long term, will find it was really 80/20 me,” she said.

But in recent years her contributions have increasingly been recognized, thanks in part to her own documentation and campaigning.

In 2009, she received an award from the engineering trade group, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

In 2020, IBM finally apologized for firing her 52 years earlier. Last October she was inducted into the National Inventors’ Hall of Fame as the co-creator of VLSI, 14 years after Mead received the same honor.

In a more personal way, Conway also touched the lives of many trans people. For years, her personal website was one of the few places where you could find clear, detailed, unprejudiced information about the experience of being trans and the process of transition – as well as a striking example of how trans people could find lasting happiness and success.

“It was the early 2000’s. My relationship with my girlfriend was falling apart. I was having a hard time containing the feelings I had when I was younger about the need to transition,” says Rebecca, a 51-year-old government worker in Colorado.

“Her site wasn’t the first one I found. But when I did find it, it opened a whole new world to me. I knew I wasn’t alone.”

Conway is survived by her longtime husband Charlie Rogers, and by her two children, four grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News