Bullet the red, white and blue sky: Why U2’s The Joshua Tree still resonates, 35 years on

In the spring of 1985, U2 fell in love with America. An extensive tour in support of their fourth album, The Unforgettable Fire, took them not just to landmark shows at major venues like New York’s Madison Square Garden but also to the towns and cities spread across the American heartland. They travelled in tour buses borrowed from country stars, complete with decorative cow horns. As they drove, they read the works of Southern Gothic author Flannery O’Connor and macho journalist Norman Mailer. They filled their hearts and minds with the myth of America.

The following year, frontman Bono and his wife Ali Hewson travelled to El Salvador and Nicaragua where they witnessed firsthand the devastation wrought by American foreign policy. The couple were shot at and watched with horror as villages were burned by US-backed rebel groups. Struck by the contrast between these competing visions of the most powerful nation on earth, the fantasy and the brutal reality, Bono sketched out ideas for the next U2 album, which he tentatively titled The Two Americas.

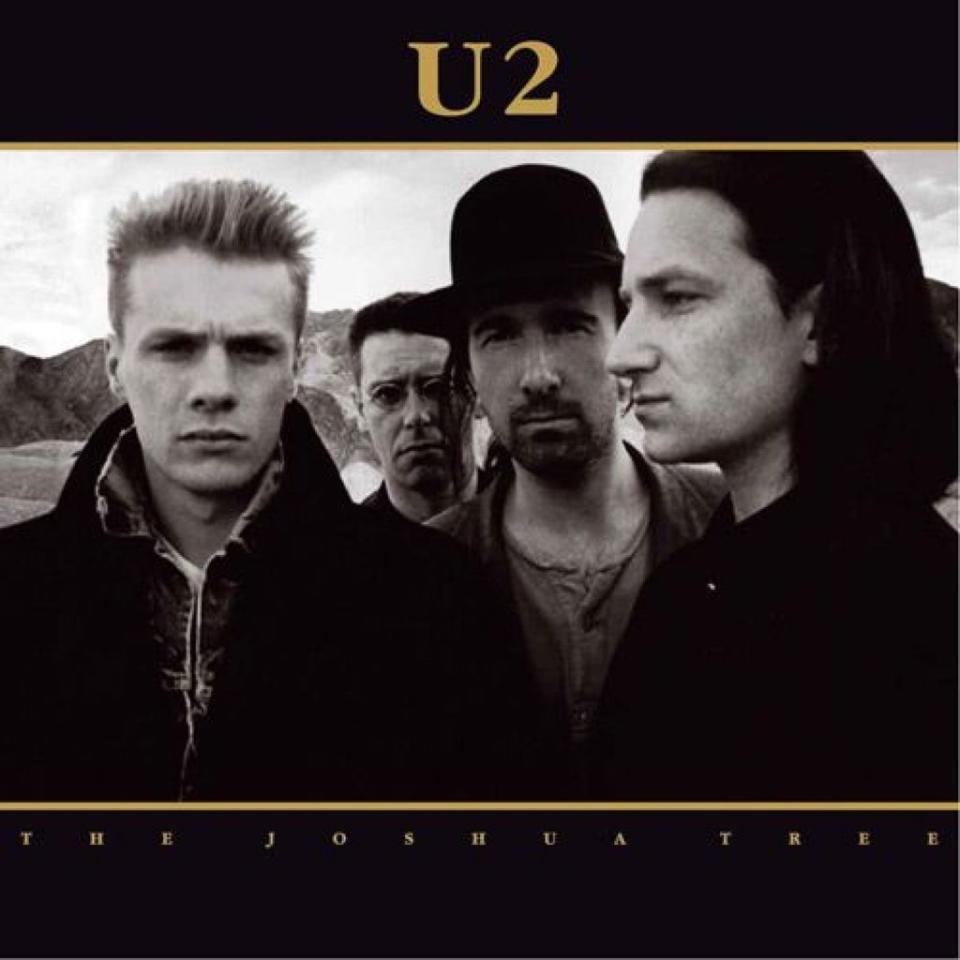

Later, during the cover art shoot with photographer Anton Corbijn in the Mojave Desert, Bono decided to rename the record. He called it The Joshua Tree, after the desert plants named by Mormon settlers after the Old Testament prophet Joshua because their stretching branches appeared to be raised in prayer. The album would become the most successful of the Irish band’s long career. When it was released 35 years ago, on 9 March 1987, The Joshua Tree became the fastest-selling album in UK chart history, spent nine weeks at No 1 in the US and has gone on to sell over 25 million copies worldwide.

In 2007, when the album was reissued, Bono explained in the liner notes about the tense dichotomy that had inspired him. “Two Americas, the mythic America and the real America – harsh reality alongside the dream,” he wrote. “It was prosperous and it was parched, and I began to see this era as a spiritual drought. I started thinking about the desert, and what came together was quite a clear picture of where I was at personally – a little off-kilter in my emotional life but very much waking up as a writer and as a commentator on what I saw around me, my love of America and my fear of what America could become.”

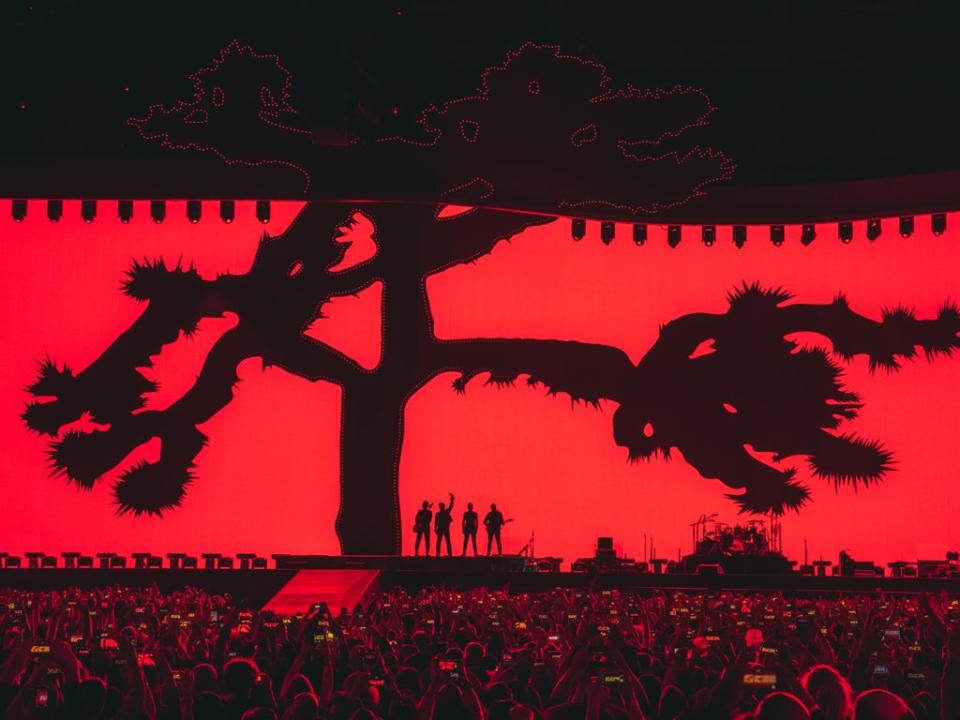

Tragically, many of its themes remain just as relevant now as they were then. In 2017, U2 toured The Joshua Tree once more to mark its 30th anniversary, and took the opportunity to point out the parallels between America under Reagan and Donald Trump. “Weirdly enough, things have kind of come full circle,” guitarist The Edge told Rolling Stone. “That record was written in the mid-Eighties, during the Reagan-Thatcher era of British and US politics. It was a period when there was a lot of unrest. Thatcher was in the throes of trying to put down the miners’ strike; there were all kinds of shenanigans going on in Central America. It feels like we’re right back there in a way.”

While the album’s title and cover art evokes the American southwest, the band recorded it much closer to home. The Edge was house-hunting around Dublin when he visited Danesmoate, a Georgian manor house in the foothills of the Wicklow Mountains. “We decided it wasn’t for us,” he wrote in the band’s 2005 autobiography U2 by U2. “But later I had the idea that the owner might rent it to us to record in.”

Bono, The Edge, bassist Adam Clayton and drummer Larry Mullen Jr all moved in, joined by producers Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois, who had also worked on The Unforgettable Fire. They converted the grand dining room into a control room, complete with tape machines and a mixing desk, and replaced a pair of massive double doors with a Plexiglass screen so that the elegant drawing room could become their live recording space. In an effort to steer away from the increasingly digitised sound popular in the mid-Eighties, the band brought in Mark “Flood” Ellis as recording engineer, after being impressed by his work on Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’ 1985 album The Firstborn Is Dead. “We just thought: This is what we want… The sound of a room,” The Edge told Mojo in 2017. “That ambience, that non-clinical feel.”

With their makeshift recording studio assembled, the band set about finding a sound that would complement Bono’s observations on the duality of America. On the thunderous “Bullet The Blue Sky”, Bono sang about seeing “fighter planes/ Across the mud huts as children sleep” and an unnamed man, who he later revealed to be Reagan, “peelin’ off those dollar bills/ (Slappin’ ’em down)/ One hundred, two hundred.” He instructed The Edge to: “Put El Salvador through your amplifier,” and the guitarist responded by making his instrument scream and wail.

The album’s closing track, the haunting, sorrowful “Mothers of the Disappeared”, was similarly inspired by Bono’s travels, a heartfelt hymn for all those who had been “disappeared” by corrupt US-backed regimes across Central and South America. “It’s kind of ominous,” Clayton told Mojo in 2017. “But there’s an optimism in the melody that we can survive these dark forces, as well as an acknowledgement that those dark forces are demonic in these situations.”

Other songs were inspired by more personal reflections. “With or Without You”, which became the album’s lead single, has been interpreted both as a song about tension in a romantic relationship and spiritual yearning. Interviewed for the 2006 book 1001 Songs, Bono said he’d been inspired by the idea that “there’s nothing more revolutionary than two people loving each other. One, ’cause it’s so uncommon these days, and two, ’cause it’s so difficult to do.”

Anthemic second single “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For”, meanwhile, blossomed out of a jam session and was heavily influenced by the love of gospel music the band had deepened while touring the southern states. The Edge had scribbled down the title phrase as a potential song name and handed it to Bono on a scrap of paper while he was singing. In a 1998 Classic Albums documentary, co-producer Lanois said he’d encouraged the band to embrace gospel as an influence. “I think it opened a door for them to experiment with that territory,” he said. “He’s [Bono] singing at the top of his range, and there is something very compelling about somebody pushing themselves. It’s like hearing Aretha Franklin almost. It jumps on you and you can’t help but feel the feeling.”

The album propelled U2 to the status of biggest band on the planet and captured the full attention of the country that had inspired it

Out of step with much of popular music at the time (it was preceded at No 1 in the US Billboard charts by Beastie Boys’ Licensed To Ill and followed by Whitney Houston’s Whitney), some critics weren’t sure what to make of it. A Rolling Stone review from the time stated that while “The Joshua Tree is U2’s most varied, subtle and accessible album … it doesn’t contain any surefire smash hits.” That verdict would be proved wrong by the mammoth success of “With or Without You”, which gave the band their first US No 1 single, and “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For”, which gave them their second. The album propelled U2 to the status of biggest band on the planet and captured the full attention of the country that had inspired it. By April 1987 the band were on the cover of Time magazine, their name in flames above the line: “Rock’s Hottest Ticket”. The following year The Joshua Tree won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year, beating Prince’s Sign o’ the Times and Michael Jackson’s Bad, much to the King of Pop’s chagrin.

Today the album remains widely regarded as the band’s finest work, both musically and politically. Its themes continue to resonate. In October 2016, a month before the election that would give Donald Trump the presidency, U2 used a searing performance of “Bullet the Blue Sky” in San Francisco to point out how far the country was drifting from its own mythical self-image. After playing a clip of Trump touting the “great, great wall” he planned to build along the country’s southern border, Bono responded directly to the figure projected onscreen above him.

“Now candidate,” he said, as the band continued to play the song’s pulsing, relentless bassline. “You understand it’s not just Mexican people who are going to have a problem with this wall of yours? It’s everyone who loves the idea of America. Like the Irish, for example. Or the French. Or the Brazilians. Everyone who loves the idea of America. Everyone who believes what they read at the foot of the bottom of the Statue of Liberty: ‘Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.’”

Bono continued to repeat that famous inscription again and again, raising a megaphone above his head. Then he ran along a walkway into the crowd, adapting the song’s closing lyrics to be about himself: “And I run, and I run, into the arms of America.” He finished the song with his arms raised above his head as if in surrender: still in love with the States, still fearing what the States could become.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News