Cartoonist Jules Feiffer Skewered Nixon and Now Trump

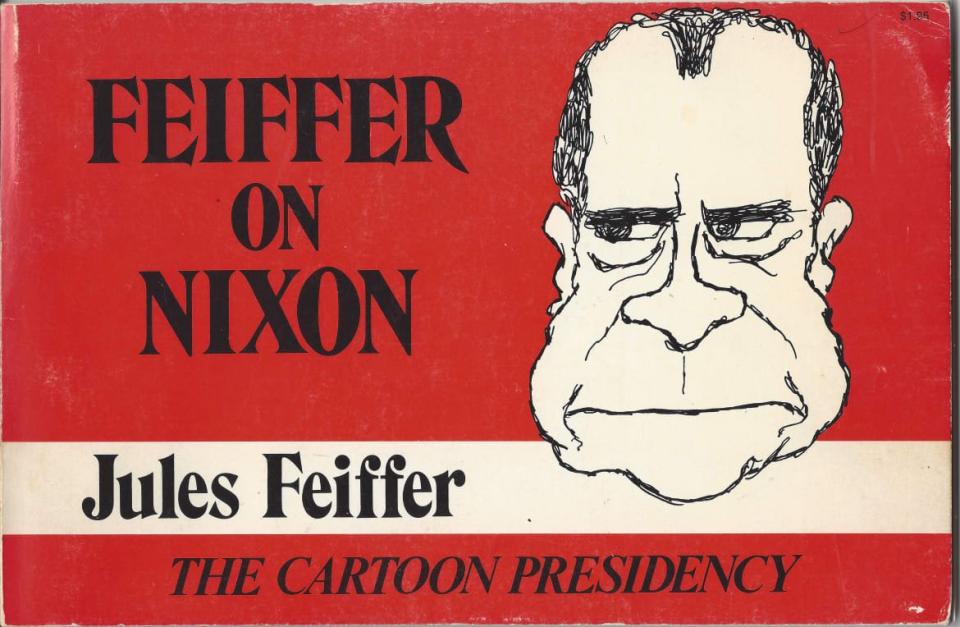

It must have seemed like the worst possible timing for a book of comics about President Richard M. Nixon. Feiffer on Nixon: The Cartoon Presidency—a collection of Jules Feiffer’s Nixon-related comics spanning 14 years from 1960 through 1974—was scheduled to hit bookstores on Sept. 20, 1974. As it turned out, a month and a half earlier, on Aug. 9, Nixon called it quits on that particular presidency. That morning, he walked out to a helicopter idling on the South Lawn of the White House and boarded with one final, suit-bunched, V-fingers-up, parting gesture.

Nixon, in a later interview with his former aide Frank Gannon, remembered that final farewell. “I kind of raised my hand. I didn’t know whether it was a salute or wave, but that was it.”

But was that really it? As Feiffer saw it, not at all. In November, tasked with promoting his new Nixon book, Feiffer gave an interview with his old friend Studs Terkel, for Terkel’s show on Chicago’s WFMT radio. Terkel introduced Feiffer and his book by saying, “And even though Nixon’s no longer president…”

Mueller’s Last Word: Nixon Won

Feiffer cut him off. “There’s very little evidence that Nixon is not president,” he informed Terkel. He went on to explain that Nixon “seems to be president of our minds and our psyches and our consciences.”

There are different types of presidents, Feiffer said. There are the ones who are elected for four-year stretches. Then there is another kind that enjoys a very different type of power.

Feiffer continued: “And it’s extraordinary… from the moment Lyndon Johnson announced he wasn’t going to run again, he almost ceased to be president, although he was still the president… One had every right to expect the same thing happening of Nixon. It hasn’t at all.”

Why? Explained Feiffer, “Nixon seems to be us.”

Long out of print, Feiffer on Nixon features 57 Nixon comics, culled from the syndicated comic that Feiffer began in the Village Voice in 1956 and continued for 41 years until 1997. Most of these are composed of six to eight panels. These panels are rarely divided by typical inked borders, emphasizing how a Feiffer comic is really an unbroken, ongoing conversation about politics, relationships, ambition, dreams, or whatever else Feiffer might have on his mind.

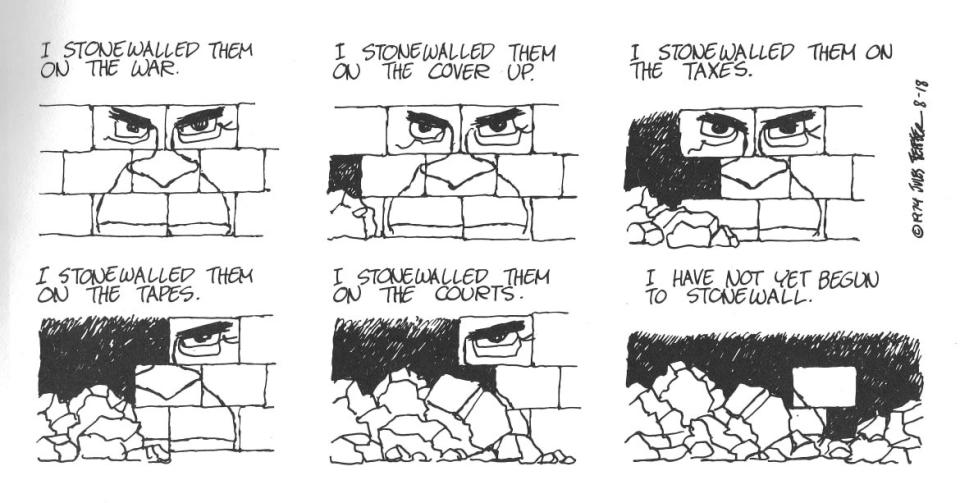

Reading Feiffer on Nixon from front to back shows both Nixon aging and Feiffer learning how to caricature him. The first comic shows Nixon campaigning in 1960. His smooth face is divided by thick eyebrows and topped with a jet-black widow’s peak. By Nixon’s first term, the familiar jowls have arrived, as has the ski-slope nose and promontory chin. Feiffer often draws this face as a floating head—a “minimalist aesthetic” as identified by Doonesbury cartoonist G.B. Trudeau, who has acknowledged that his own iconic, Nixon-era works owe Feiffer a significant debt. (A comic in this collection about stonewalling is particularly suggestive of a concurrent Doonesbury strip of a wall being built in front of the White House.)

Feiffer’s eye for caricature is masterly, both in art and prose. In his later book Jules Feiffer’s America: From Eisenhower to Reagan, he vividly described the Nixon look: “His eyes darted like pinballs. His battered head drooped low on his tin body. His shoulders met his eyebrows, his arms waved like tollgates, his legs like prosthetic devices. He was our favorite sick joke. But the joke was on us.”

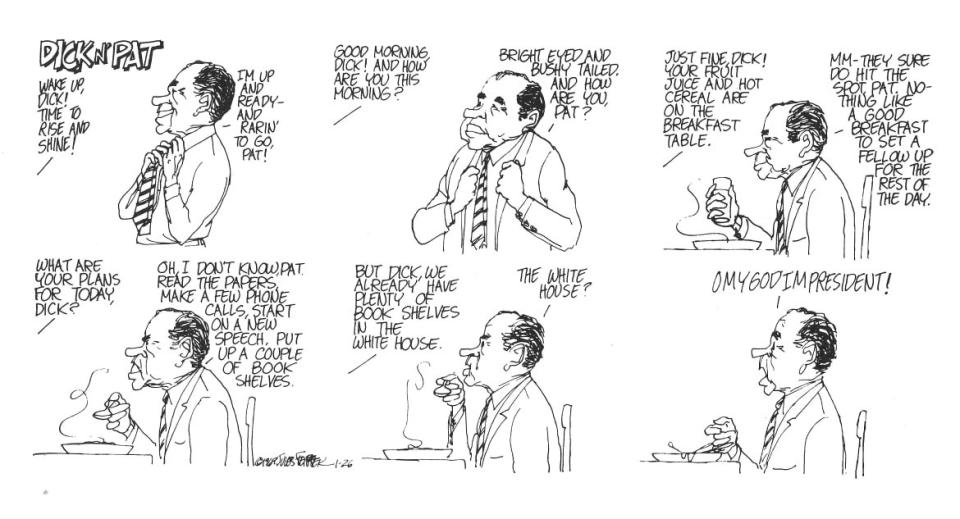

Some of those jokes in Feiffer on Nixon pay a debt to the old radio shows that inspired Feiffer’s script-like comics writing, none more so than the “Dick n’ Pat” occasional series, which allows us to eavesdrop on Richard and Pat Nixon like radio audiences would listen in on George Burns and Gracie Allen, or especially Paul Rhymer’s Vic and Sade. In one, Dick’s rosy morning is spoiled when Pat reminds him he’s been elected president; in another, Feiffer predicts Ronald Reagan’s cinematic presidency when Pat reminds Dick that “this isn’t a movie,” and Dick responds, “If this isn’t a movie this country’s in a lot more trouble than you think.”

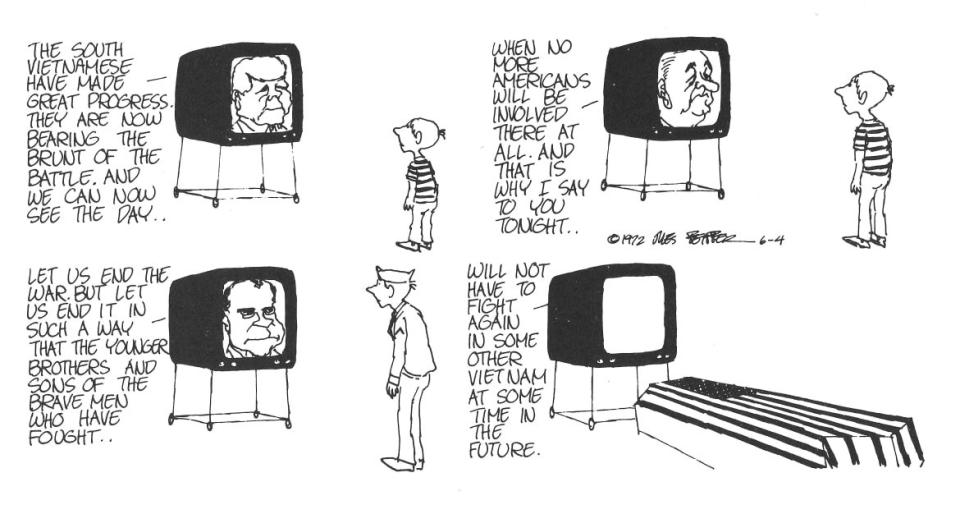

There are numerous comics about the war in Vietnam, none more stark than a series of drawings of a boy growing up watching television and a succession of three presidents—John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Nixon—promising to end the war. The comic ends with the television broadcasting to a flag-draped casket. Equally sobering is a comic written as a parable—complete with a “Once upon a time” beginning—that traces the tragic assassinations of the ’60s, culminating with a quote from none other than Spiro T. Agnew: “The disease of our time is an artificial and masochistic sophistication—the vague uneasiness that our values are false.”

Recently, I re-read Feiffer on Nixon while, in the background, live impeachment proceedings played over my computer. It produced a feeling that, at least for a short time, mimicked a sense of calm. While the faint voices of Matt Gaetz and Jim Jordan wafted into the room, Feiffer’s cartoons offered some hope that a well-wrought Constitution can survive a leader of ill will, even one prone to despotism.

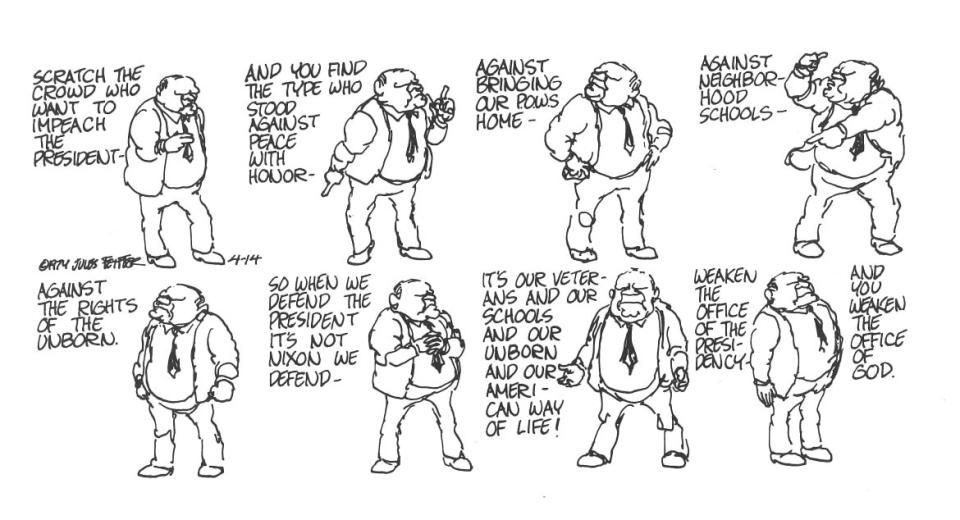

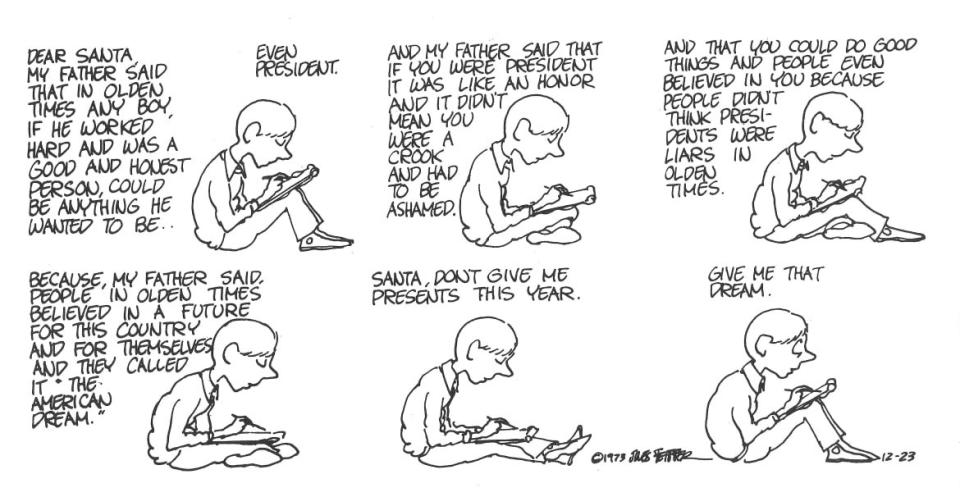

Yet other Feiffer cartoons aren’t so reassuring. Cartoonist Mike Lynch, in his blog, once posted how he came across Feiffer on Nixon in a local flea market and was amazed by how many of those comics are on point today. In fact, some seem to leap across the decades and speak to the Donald Trump presidency even more than they addressed the Nixon years.

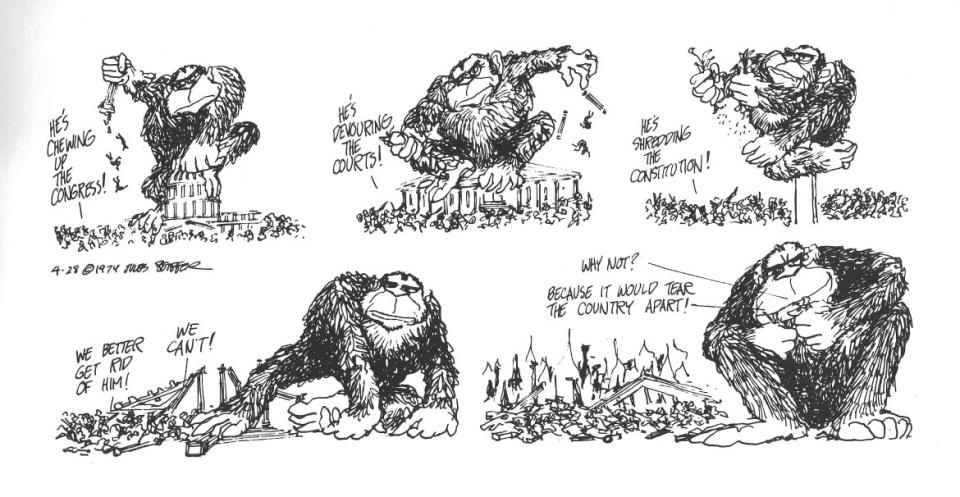

Such is the case with a comic of Nixon addressing the country, stating that he has brought law and order to the press and “renegotiated” the Constitution. He finishes with, “Now I want to inform you of my plans for a third term.” Another comic shows Nixon’s face on King Kong’s body, with citizens fleeing beneath the beast’s feet, screaming, “He’s chewing up the Congress! He’s devouring the courts!” As this Nixon-Kong rampages across Washington, D.C., a tiny voice comes from a victim in his deadly grip, worrying that resisting the monster might “tear the country apart.”

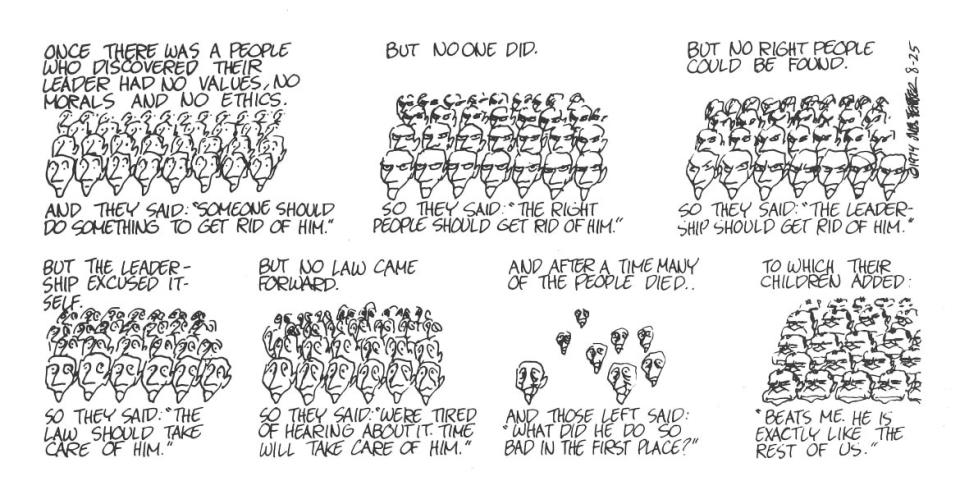

But no comic in Feiffer on Nixon is as chilling as one dated Aug. 25—drawn shortly before Nixon’s resignation but not published by newspapers until after Nixon’s final march across the South Lawn. In it, panel after panel shows rows of identical faces. “Once,” Feiffer writes, “there was a people who discovered their leader had no values, no morals and no ethics. And they said: ‘Someone should do something to get rid him.’ But no one did.”

Nobody steps forward—not political leadership, not the law. After a time, Feiffer continues, many of those clamoring for the leader’s removal die off. The survivors wonder, “What did he do so bad in the first place?”

These descendants can be seen in the final panel, each one with a face identical to Nixon’s.

“Beats me,” these children in the nightmare comic respond. “He is exactly like the rest of us.”

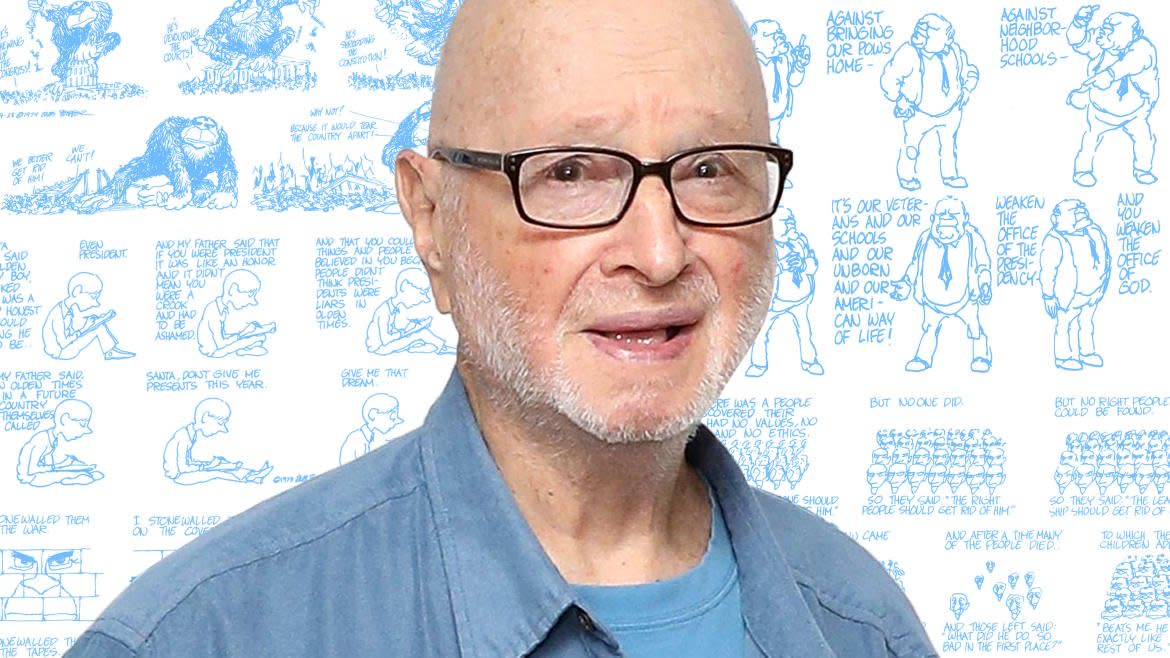

One recent snowy morning on Long Island, I had the chance to visit with Jules Feiffer for a filmed interview for Improv Conference NOLA, a New Orleans-based arts and literary festival. Near the end of the interview, I placed my copy of Feiffer on Nixon in front of Feiffer himself, and opened it to the parable of the leader that nobody would remove.

Feiffer, who turns 91 this month, first noted with some amusement that I had purchased a used copy of the out-of-print book and had left the $4 price penciled in the inside cover. Then he started reading the comic. Of the thousands of comics he’s drawn in his still-vital career, this was one he’d forgotten.

He read each panel out loud, until he reached the conclusion: a nation populated by little Richard Nixons. Nobody had to state the obvious parallel to Trump’s presidency: Will this era begat new Trumps? Feiffer finished reading and looked up. “Oops, I tripped over it,” he joked about his own prescience.

Feiffer continued: “These were things that have been with us since the very beginning, and that’s essentially what got me to go into this work, hoping I had an effect, and all I had was a good time.”

I told him I didn’t agree. Feiffer’s comics in The Village Voice opened the door for personal, insightful, introspective, and often viciously satiric comics in the alternative press. His influence on the national conversation is immeasurable.

“I think what I’ve done is make people who feel lost less lost because I’m there with others doing similar work,” Feiffer said. “But the one thing I’ve learned as an old man is that this is a country without a learning curve. We don’t learn, and the reason we don’t learn is because we don’t regard history as serious… History is the past for us, history has nothing to teach us, and if it did, we wouldn’t want to be taught, go fuck yourself.

“We’re not just against public education, we’re against education… Because learning means you learn things that may be unpleasant to learn, and information may not be useful to you in terms of your preconceptions and prejudices. Fuck that, that’s not fun.”

In addition to graphic novels—over the past decade, Feiffer published a wonderful film noir-style trilogy of books set in the middle of Red-baiting and McCarthyism—Feiffer now draws “American Follies,” a monthly comic for the website Tablet Magazine. These works are every bit as biting as his works from a half-century earlier. In one, an interior monologue penned on Trump’s obscenely long necktie features references to Roy Cohn, who happens to have been Feiffer’s cousin. Another is a pas de deux of a man and a woman unable to say anything to each other beyond Trump’s name, even shouting the name to each other while making love. It’s a horrific update to the assertion that Feiffer once made to Studs Terkel about how someone can become the president of our minds and psyches.

“The president affected much more than the politics of the country,” Feiffer says. “And you see it with Trump. He created a social style of what was acceptable and not acceptable in all forms, not just political, but social, interpersonal behavior. The way we react to one another, whether we’re kind or the way we’re paranoid or suspicious. Somehow it’s all centered in the White House and spreads out.”

Feiffer considers it his good luck to have had Franklin D. Roosevelt as his childhood president, which introduced the idea to his young mind that government can be a force for good in people’s lives. “One thought, as a boy in the Bronx growing up with immigrant parents, that that is what government is, that’s what the great thing about America is.”

Nixon was something different. “The thing about Nixon—it wasn’t that Nixon changed anything, it was that Nixon as a personality, his own avarice, bad character and corruption, was like a mob, a gang, taking control of the White House. They were all crooks. And I did several cartoons in which I showed them as mob members, wearing dark glasses, and Nixon being the ruler of the mob, because that’s what they were. And the most wonderful line Nixon ever stated, as everybody loved, was ‘I am not a crook,’ because we all knew he was.”

As for the current president, “He’s bringing us back the real America. That’s it. Making America great again is making America openly bigoted again. You had to hide the bigotry during the liberal years. Now we don’t have to hide it. And that’s what you see in the Trump rallies. That’s what you see with his crowds… He’s licensing his followers to behave as badly as they once fantasized but didn’t dare. And he’s saying, ‘Let’s stop fucking around, this is who we always were.’”

Feiffer recalls what he considered the callous response of many Americans to the news of the My Lai massacre—comparable to the widespread acceptance today of the forced separation of families at the Southern border. It’s not due to any lack of information, as Feiffer told Studs Terkel in 1974. It’s just “the process of denial, over and over again.”

Those looking for punch lines in Feiffer comics might be disappointed—that’s not how he regularly chooses to punctuate his stories. Similarly, in both a Feiffer comic and Feiffer conversation, there is no rush to a hopeful conclusion.

“As Martin Luther King famously said, you have these fights over and over and over again, but the arc goes toward freedom,” Feiffer says. “Well, I’m not so sure the arc necessarily has to go that way.”

And as with the Nixon seen in Feiffer on Nixon, no matter when and how Donald Trump finally does make his exit, this new presidency of our mind doesn’t appear to be going away soon.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News