Cash for questions: what's next for big-money gameshows?

In 2000, the garden designer Judith Keppel began to think she could win Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? “The show had only been going for two years but it was huge – we’d never had a cash prize that big before – and I started to realise the questions weren’t that hard,” she says. “I began calling in to try and get on, so much so that BT rang me at one point to ask whether someone else was using my line. After about 250 attempts and a huge bill, I made it.”

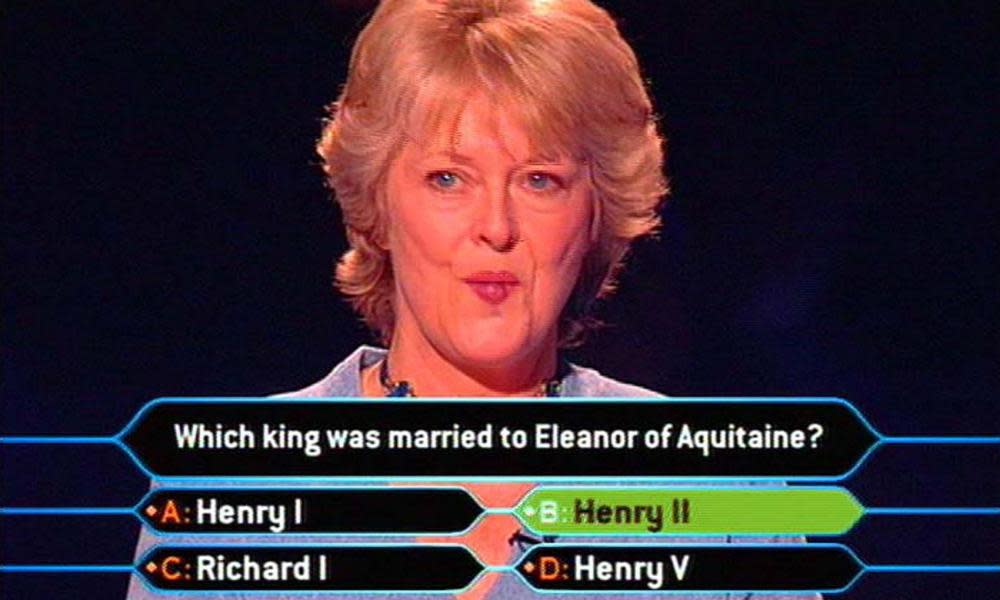

On 20 November, Keppel became the first person to win the show in the UK and leave with £1m. Her winning question was “Which king was married to Eleanor of Aquitaine?” (the answer is Henry II). “Winning absolutely changed my life because, at the time, I was worried about money since I was in between jobs,” she says. “After the win, the media response was huge and I was asked to do all sorts of funny things like open flower shows and then I was offered Eggheads in 2003, which is what I’ve been doing ever since.”

At its peak, the year before Keppel’s win, Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? was bringing in 19 million viewers per episode. “With Millionaire, we had our Concorde moment,” the gameshow producer and quiz writer David Bodycombe says, “it was the largest prize we’d seen on British TV and it was pulling in the biggest ratings as a consequence. It’s been difficult to know where to go from there in terms of rewards for contestants.”

Ever since the BBC launched its first televised gameshow, Spelling Bee, in 1938, the prize-winning format has been a staple of the nation’s viewing habits. The development of aspirational materialism in the 50s led to a spike in shows with seemingly glitzy new offerings, including popular iterations such as Double Your Money – with an initial cash prize of £1,000 – and Take Your Pick. In subsequent decades, TV personalities cemented viewerships for shows such as The Generation Game with its host Bruce Forsyth and Blankety Blank with Terry Wogan.

Early prizes were middling at best, though, ranging from the holidays and household appliances of The Generation Game to the bizarre chequebook and pen in Blankety Blank. Much of this was owing to broadcast restrictions that came into force after the “quiz share” scandal in the US in 1958, where producers helped contestants to win big money prizes, placing a £1,000 cap on the value of prizes on British shows from 1960. This increased to £6,000 by 1981, but it wasn’t until the restriction was scrapped altogether in 1993 that the money could rise to Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? levels.

The 00s then saw a brief leap forward, with producers competing with Millionaire to offer £1m on shows such as Poker Face, the Vault and Red or Black, leading to big winners including Graham Fletcher, who picked up £1.5m on Red or Black and Sarah Lang who won £1m on Poker Face. Yet, the years since have seen offerings drop off a cliff, with Davina McCall’s The Million Pound Drop plummeting to The £100k Drop in 2018, Tipping Point only offering a £10,000 prize and a revamped Supermarket Sweep giving contestants the chance to win just £3,000.

Since washing machines and microwaves don’t quite inspire the same level of awe as they might have done in the 60s and 70s prize hauls, why are people still lining up to get on to TV gameshows?

David St John holds the world record for having appeared on the most British gameshows – 34 between 1982 and 2013. “You never forget your first time,” St John says. “I remember getting on Sale of the Century with Nicholas Parsons and winning two Honda mopeds back in 1983. Since then I’ve been addicted.” St John estimates that in his decades spent quizzing, he has won about £15,000.

“You have to do it just for the fun of it because you can’t really win that much,” he says. “Everybody wants their 15 minutes of fame since it’s still a major achievement to get on TV but when it comes to gameshows, it’s all about skill.”

For St John, his “holy grail” show to compete on is Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?. “You have to have talent to get on a quiz show, as opposed to reality TV where you have to just make an omelette or something,” he says, “and the quizzing level has really improved in recent years with shows like Only Connect, so now it’s even tougher.”

Keppel puts her own win down to luck, as well as knowledge. “I was so lucky I didn’t get any questions on sports or soaps,” she says, “because even with answers that you might know, under the studio lights you can buckle so easily.” To add to the pressure, Keppel’s winning round had a five-day gap in between filming sections, since she was the third contestant and so ran out of time during the live taping of her opening rounds. “My heart was thumping all week and all I could do to calm myself was go on long walks,” she says. “It shows you how much confidence Charles Ingram must have had to go on cheating so obviously when he did.”

That notorious incident is now the subject of an ITV dramatisation, Quiz. Starring Michael Sheen as Millionaire presenter Chris Tarrant and Matthew Macfadyen as Ingram, it tells the story of army major Ingram’s 2001 appearance on the show and winning of the top prize with the aid of an audience accomplice who coughed when the correct options were read out.

Cheating notwithstanding for the participants, the former gameshow contestant and current Egghead Lisa Thiel believes it is the sofa play along element of gameshows that keep them so enticing to viewers. “People love seeing others under pressure and thinking they could do it better themselves,” she says. “I applied for the Weakest Link when I was just out of university since I wanted to be famous and win some money. Of course, I did neither; as soon as they started taping, my knees were shaking and I had to hang on to the podium to make sure I was even standing.”

Thiel ultimately, like St John, believes the thrill of playing has to overcome the generally poor prizes – £5,000 is the most ever won on the regular UK version of the Weakest Link. “You have to find something else that people are willing to compete for,” she says. “People still want to go on telly for the glory of it, to be with Bradley Walsh on the Chase or Richard Osman on Pointless.”

For the prizes, though, Keppel thinks there now needs to be a new goal for Millionaire. “They need to jump the prize to £5m – that feels like a new, life-changing amount,” she says. While Bodycombe thinks that with more than 60 gameshows being produced every year, cash is no longer king in making formats stand out. “There’s been several rumours of shows giving away trips to space. That could potentially be the next big frontier for gameshow winners.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News