'Ceremony saved my life': Ochapowace First Nation man healing through culture and dance

WARNING: This story contains details of experiences at residential schools.

An Ochapowace First Nation man says going to ceremonies and participating in cultural events has been a big part in his healing from the trauma of residential schools.

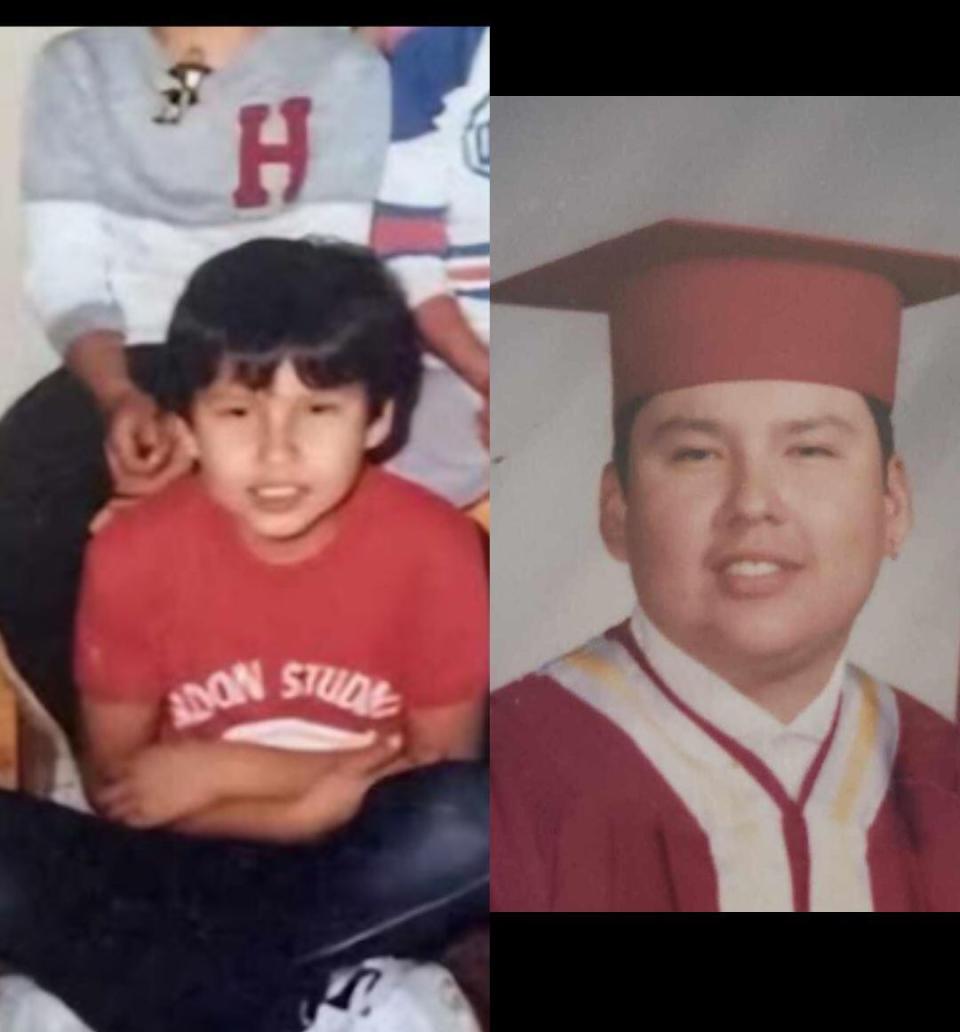

Ivan Isaac spent 10 years of his childhood in three different residential schools in Saskatchewan — Marieval Residential School, Gordon's Residential School and finally Lebret Indian Industrial School, where he graduated in 1998 — the year the school closed.

"I didn't realize how much it affected me," Isaac said. "I just thought I hated being an Indian."

When he graduated, he returned home to his home reserve, Ochapowace First Nation, about 160 kilometres east of Regina, where he played sports for the community's local teams. He said it wasn't uncommon for him to encounter racism as he travelled for sport.

During that time, Isaac also lost his little brother. The hostility he felt outside his community, because of his Indigenous identity, coupled with his grief, led him into a deep depression, he said.

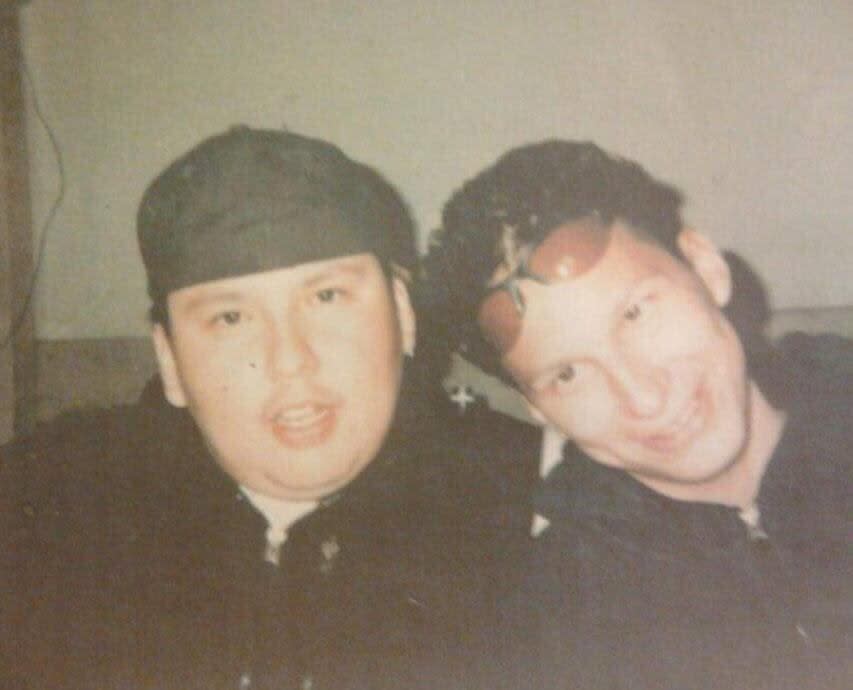

Ivan Isaac with his little brother, Jimmy Dean Isaac. (Submitted by Ivan Isaac)

"I didn't know how to grieve, so I hit the bottle hard and I blamed my brother for leaving me," he said. "I blamed him for years, and it wasn't even his fault."

Isaac said he used alcohol as a coping mechanism for years.

"I thought I was numbing the pain, which I wasn't," he said.

Healing through dance and ceremony

As the years passed, Isaac lost many friends to addiction and suicide. In his late 30s, he decided he didn't want to die. He decided to get sober and pursue knowledge instead.

Isaac started studying at the Regina-based First Nations University to pursue a career in education.

That was when he learned more about the impacts residential schools had on Indigenous communities.

When he started a teaching practicum, the feelings he thought he had suppressed from his own residential school experience came flooding back, Isaac said.

"I had to push through … and keep a smile on my face. I would teach through the day and come home and cry my eyes out, and do it again the next day," he said.

"But it was healing, because if I didn't go through that, I'm thinking I would still carry that."

Left, a photo of Isaac at Gordon's Residential School, and right, his graduation photo from Lebret Indian Industrial School. (Submitted by Ivan Isaac)

That was also when Isaac began to want to dance powwow. He was in a beading class and met someone who made regalia, and she helped him put together an outfit.

"Cool things have been happening ever since I've been dancing," he said. "And since then I've been trying to give myself to the Creator and offer what I can."

Isaac says he's also started to pay it forward. He now makes powwow regalia, just like the regalia he was given when he started, and gives the special items to new dancers.

This year, Isaac is going to be initiated into the powwow circle in his home nation of Ochapowace.

Isaac says growing up, he never felt like he belonged anywhere. But when he started going to ceremonies, he was welcomed in with open arms.

"When I go to my ceremony family I feel like I belong, and they accept me for who I am, with all the flaws, and all the good things. They accept me for me."

Isaac said he taught the kids he worked with in his teaching practicum about Indigenous culture and the power of dancing powwow.

Isaac says he wishes he could have always danced powwow. He is happy to be on this path now, and says it is never too late to start learning. (Submitted by Ivan Isaac)

"Some of these kids, these inner-city kids, Native kids, they haven't even seen anything like that, and that blew my mind," he said. "To show them a little bit of smudging … was cool."

Sharing cultural teachings with the kids really helped him, because it was something he always wished he knew about growing up.

Isaac lost another brother this year, but now that he's sober, he's allowing himself to grieve in a healthier way this time, he said.

"I'm really trying to stick to the culture because it's really helping me find my way."

Isaac said when he feels the grief of what he went through and the loss of loved ones, he turns to ceremonies to help him, and that his ceremonial family helps him stay strong.

All of these healing practices have helped him feel proud of his First Nations identity, Isaac says. He plans to continue learning more about his cultural ways and share what he's learned with others.

"Ceremony saved my life," he said.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line is available to provide support for survivors and those affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour service at 1-866-925-4419.

Mental health counselling and crisis support are also available 24 hours a day, seven days a week through the Hope for Wellness hotline at 1-855-242-3310 or by online chat.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News