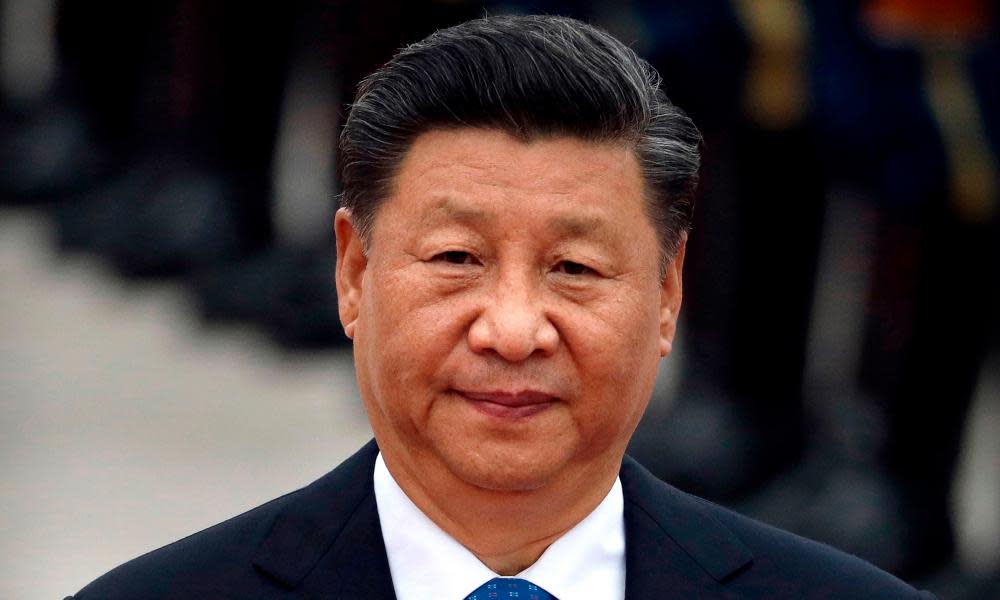

Chinese journalists to be tested on loyalty to Xi Jinping

Chinese journalists will soon be required to pass a test grading their understanding of Xi Jinping Thought, the socialist teachings espoused by the country’s leader.

A notice from China’s media regulator has been sent to more than a dozen state-owned news organisations in Beijing over the last month. It instructs employees to prepare to take an exam on the “study Xi” propaganda app, launched earlier this year, in order to have their press credential renewed.

Most believe the regulation will soon apply to Chinese reporters across the country. Journalists from three media organisations, two of which were outside Beijing, told the Guardian their publications had also received informal notices to register on the app.

“From the top down to the bottom, I don’t think anyone will be able to escape it,” said one reporter from a broadcaster in the eastern Shandong province who said he was not authorised to speak on the topic.

The on-site, closed-book exam, to be administered by news organisations in early October, will be divided into five parts, including two on Xi Jinping’s teachings on socialism for the new era and Xi’s “important thoughts on propaganda”, according to Media Reform, a self-published news account on WeChat.

News of the test, first reported by the South China Morning Post, comes as Chinese media face increasing restrictions. China is considered one of the least free countries to operate as a journalist, ranked 177 out of 180 in 2019 by Reporters Without Borders, above Eritrea and North Korea.

While Chinese journalists face jail time and self-censorship is common, journalists especially from independent publications often push the envelope, investigating cases of local or corporate corruption. To get a press credential, journalists have previously been tested on their understanding of “Marxist journalistic ideals.”.

“To be honest, it doesn’t mean that much,” the journalist from Shandong said. “Still, it’s a move to restrict public debate.”

Authorities have stepped up their regulation of Chinese media and the internet, which already limits access to foreign websites, including news sites. In July, a draft regulation under China’s social credit system proposed punishing citizens for publishing information that “violates social morality” or causes “adverse social impacts”.

Xi has demanded loyalty from Chinese journalists before. In 2016, he told staff at three state-run news outlets in Beijing that they were “the propaganda fronts and must have the party as their family name”.

According to Media Reform, the exam for journalists is not expected to be difficult. The notice sent to reporters from their editors said news organisations should establish study groups and begin preparing for the test. Sample questions will soon be uploaded to the app, according to the news website Sohu.com.

The test will only be able to be retaken once. Journalists said they were not sure whether they would need to take it every time they renewed their press cards, done every five or six years.

While some journalists said they resented the new rule, others were less critical. “Chinese society needs to strengthen political study and correctly lead public opinion,” said a reporter with a paper in the south-western province of Guizhou, who asked not to be named.

“Western media may be able to report on anything they want, but they also still pay attention to the ideology of their countries,” he said.

Additional reporting by Lillian Yang

Yahoo News

Yahoo News