A Christmas hit can be the gift that keeps on giving, so why have so many artists given up?

As Mariah Carey and Wham continue to rule the yuletide charts with decades-old songs, it seems many contenders have abandoned the festive fight

To me, the Christmas season doesn’t start when offices close. It’s not when the first person on the street turns on the Christmas lights, or even once the Christmas pageant has been held.

It’s the first day I hear a carol.

Everyone’s got their favourites. It might be a classic or a cover, religious or secular, joyful or sad. Whatever it may be, and however much we might roll our eyes, it’s a great time for music.

Which means a great time for musicians. Christmas music has long been helping artists make money. In fact, the Guinness Book of World Records calls Bing Crosby’s 1942 White Christmas the bestselling single of all time, with more than 50m sales worldwide.

There was a time when releasing a Christmas album was an artist’s best hope at making a few dollars, and while there’s no exhaustive source of album releases, Allmusic data suggests there were more than 230 Christmas albums released in 2001.

Source: author calculations based on Allmusic

By 2011, that number had plunged to a little over 90. A rough early count suggests that this year, the tally will be about 60.

What’s with the decline of Christmas albums?

First, it’s symptomatic of the slow demise of albums more broadly. As musical technology and formats have changed, so too have preferences. In the 2010 calendar year, Australians bought 33m CD albums. By 2020, the number had dropped to 3.3m – one-tenth of the value it was 10 years ago. In a return to retro, forecasts suggest that in 2021, we probably spent more on vinyl than on CDs.

CDs defined the album format. A CD can fit 74 minutes of content – the length of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Fans were willing to pay a premium for an album ($20-$30) over a single ($5-$10). Labels and artists designed albums with two to three hopeful hits (which would be spun out in to singles), and a balance of filler tracks. The practice was both common and common sense.

Now, of course, there is streaming.

According to 2020 figures, streaming represents 89% of total recorded music sales in Australia by value. By all accounts, you’re more likely to see a subscription gift card in your email this year then you are to see a CD wrapped underneath a tree.

Related: Rockin’ around the Christmas streams: why festive music is bigger than ever

Artists and labels have adapted accordingly. Under streaming models, music makers get paid every time someone listens to a track – or the first 30 seconds of it. The result is more focus on singles, and shorter track lengths. You could break a three-minute song in to two one-and-a-half minute songs, or three one-minute songs, and get paid double (or triple) as much for your efforts.

The other contributor is that streaming provides better access to a wider catalogue.

In a physical music store, constraints around distribution and physical space meant that artists were very reliant on labels and networks to get access to consumers. Whether a single or an album, you could only take up shelf space for so long. Music had a short half-life.

Online, however, there are few limits. Musicians can reach audiences of millions without labels – a Scottish man singing a Kiwi folk song on a social media platform became the song of a pandemic, with more than 75m views.

It’s also enabling access to golden oldies – and increasing focus on them. Older Christmas songs have become increasingly prominent on Spotify charts over the last five years. As an example, consider the most streamed songs in Australia on 20 December from 2017 (the first year Spotify chart data is available) onwards.

In 2017, every song in the Top 10 had been released that year. In 2018, Mariah Carey’s 1994 festive hit All I Want for Christmas Is You made the list – and it has featured in the Top 10 every year since. Three out of the Top 10 streamed songs on Spotify in Australia on 20 December 2021 were from previous years.

This is not to say that there have been no new contenders. This year, Ed Sheeran, Kelly Clarkson and Megan Thee Stallion have all thrown their hats in to the ring. Yet none have made the Christmas week Top 50. It’s no wonder that festive new releases have declined.

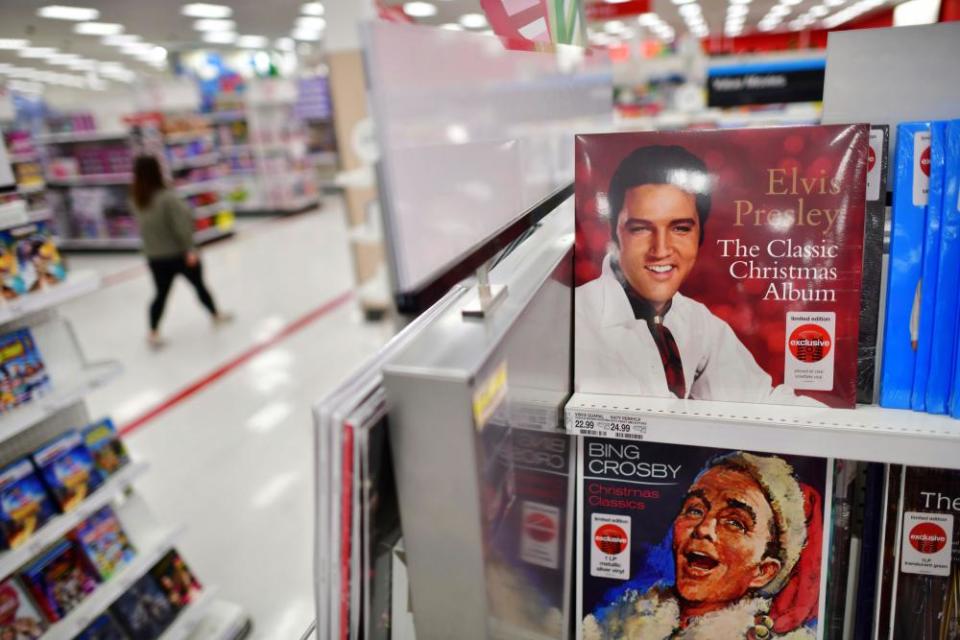

Nostalgic Christmas listening is not limited to streaming. Consider the classic crooners making money from beyond the grave. There has been at least one Christmas album release from Bing Crosby, Elvis Presley, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra or Nat King Cole every single year for the last decade. Not bad considering none of them have not seen a Christmas in more than two decades.

Source: author calculations based on Allmusic

Love them or hate them, Christmas songs are here to stay. So turn it up and make the most of it while it lasts – January is only a week away.

• Jessica Mizrahi is an economic consultant and commentator. She has taught, researched and applied economics for over a decade

• The author previously served on the board of the Australian Live Music Business Council and has previously co-authored research commissioned by the Australian Independent Record Labels Association. All opinions and analysis are her own

Yahoo News

Yahoo News