Coldplay have always been cool, and it’s ludicrous to claim otherwise

It was the kohl-eyed cultural assassin Super Hans who struck the killer blow. “People like Coldplay and voted for the Nazis,” Peep Show’s resident joker infamously told Jez in one 2005 episode of the sitcom. “You can’t trust people.” Granted, he was arguing that Jez’s new pub should be themed as a working laundrette and not serve lager, but this wild illogic acted as judge, jury and saucer-eyed executioner on the perceived credibility of Chris Martin and his three band members who, despite popular misconception, also have names.

In the two decades since, from pub to panel show, Coldplay have become shorthand for dull, mimsy musical Evian: industry bigwig Alan McGee dubbed them “bedwetters”; John Oliver likened their listening experience to “sex with the lights on” (which is better, right?). More than any other band of their era, however, Coldplay make the debate surrounding their so-called “coolness” seem about as pointless and ludicrous as a Tory 2024 manifesto.

To this day, proving that the human mind is a baffling cosmos where logic goes to die, “people” have lauded the jubilant poptimist breakthrough of Dua Lipa headlining Glastonbury and, in the very same tweet, had a crack at her fellow, equally pop headliners.

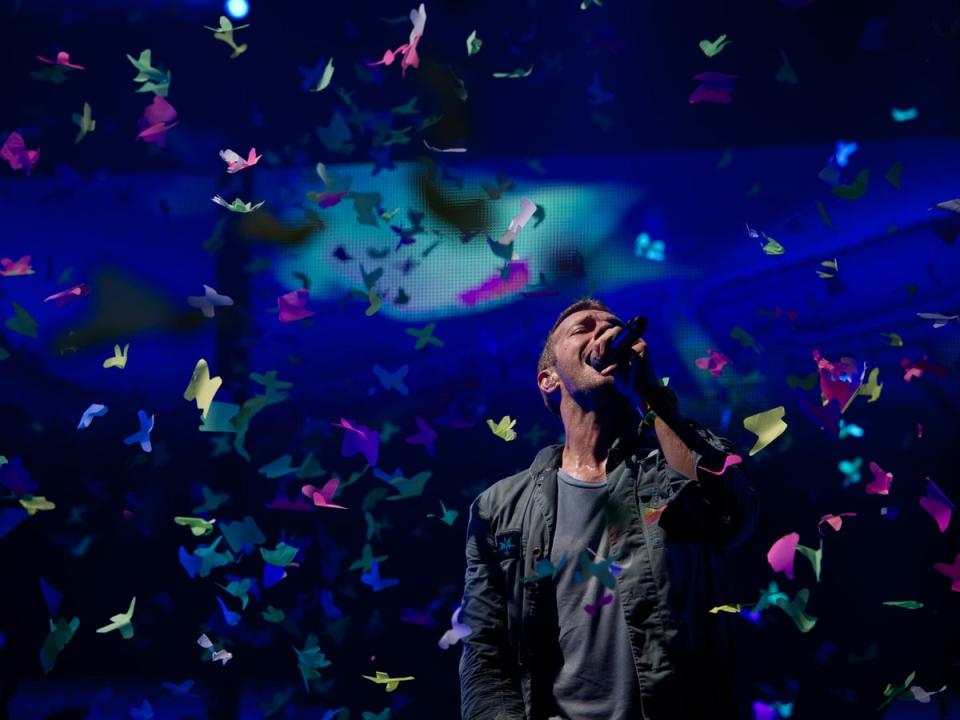

I have the opposite issue. I’m as weary of all the culture-throttling mainstream acts as the next outmoded indie troll with a heart of tar, but – and it still feels like it’s my turn to share at a support group meeting every time I announce this – I adore Coldplay. I share much of my cultural taste and outlook with Fat White Family, but watching Coldplay makes me laugh, weep and sing. Were I king, all of the Coldplay-adjacent faux rock bands like Bastille, OneRepublic and Maroon 5 would be clapped in irons in the tower awaiting medieval retribution for their crimes against sound, but when Chris Martin bounces down an ego ramp in a suicidal paintballer’s T-shirt wailing “oh-oh-OOO-a-ooooh-oh” as confetti canons transform the stage into air strike on Teletubbyland, my heart lights up like a “Fix You” firework.

Such a superhuman capacity for musical cognitive dissonance comes with much dilemma for the professional cynic. While it’s in my marrow to sneer along with the widespread Coldplay disdain and cackle wickedly at the backhanded jibes, I’m plagued by an inner fanboy who simply doesn’t understand how these people can’t see the experimental pop daring of 2008’s Viva La Vida or Death and All His Friends. How their dumbstruck inner child has never gawped across a stadium turned into a neon Pollock by 90,000 light-up wristbands. Or how Martin somehow captured the precise moment in a relationship when everything falls to pieces on “The Scientist” in 2002.

To my mind, the last 20 years or so of simmering global Coldplay hate has been a symptom of a super-spreading “Yellow” fever pandemic. When 2000’s ubiquitous breakthrough hit inspired so much more ordinary multi-platinum fare from the likes of Snow Patrol and James Blunt, the people who never bothered to go and see what a spectacular, exuberant and life-affirming show Martin and co put on began considering Coldplay as a byword for beige, boring wimp-rock. They were music’s penne carbonara. Its Outnumbered. A Richard Osman novel.

If you wait long enough, though, eventually everything except Laurence Fox and gonorrhoea becomes quote-unquote cool. Of late, pundits have been pointing to Coldplay’s record-breaking fifth Glastonbury headline slot as a sign of some kind of credibility rehabilitation. The band are not only the subject of a new eight-part Radio 1 re-evaluation titled Music Uncovered: The Genius of Coldplay, but the more clips of Coldplay’s effervescent performances filter onto the feeds of pop-friendly TikTokers, and the more that dissing performers has diminished as the done thing, the more the act of hating them has become basic and passé. Coldplay are being rediscovered by Gen-Zers wondering who this bunch of psychedelic supply teachers collaborating with Selena Gomez and BTS were. Dumping on them is what their dads do.

“They shouldn’t be judged by rock’s rules,” Bono says in The Genius of Coldplay and, for perhaps the first time since around 1987, the U2 frontman is worth listening to. Coldplay are an impervious presence now; an intrinsic element of pop culture itself, a cloud their critics can only shake a fist at. The 90,000 people having the time of their lives to the millennial generation’s biggest pop-rock crossover phenomenon at any of their (count ’em ) six Wembley shows last year didn’t care which side the zeitgeist had got out of bed that day – any more than the hen parties down at Abba Voyage do.

If there’s a historical equivalent, it’s Fleetwood Mac. Once dismissed and derided by the punk mob in 1977 – largely on the basis of their monumental sales – the Mac eventually became the toast of the 2010s album-oriented rock revival, feted by Chairlift, Haim, Vampire Weekend and Best Coast, and sampled into Balearic bliss states. Their music hadn’t changed, it just became acceptable to admit it was brilliant all along.

The same, increasingly, goes for Coldplay. They hit Glastonbury 2024, then, with arguably their strongest ever tailwind of goodwill behind them. And, with Martin once again suggesting the band might be approaching their end (as he has with every album since at least 2014’s Ghost Stories), a fair amount of event status, too. That said, it’s perhaps ironic (or telling) that they’ve reached this turnaround moment at a point when they’ve discarded any sort of alternative pretence.

There’s no point, impact, edge or originality in still hating Coldplay after all these years

Their most recent album, 2021’s Music of the Spheres, fully embraced their standing as mainstream synthpop titans, inhabiting the same exalted echelon as your Swifts, Beyoncés, and Gagas. The uber-populist shift that began with Rihanna guesting on 2011’s Mylo Xyloto and pop production duo Stargate getting their sizzling mitts on 2015’s A Head Full of Dreams has reached its apotheosis. It’s hard not to conclude that the cultural cause has given way to the commercial. Coldplay in 2024 arguably exist purely to maintain the business of Coldplay.

But this gradual re-nosing of purpose has worked in their favour, enabling them to shrug off the haters. There’s no point, impact, edge or originality in still hating Coldplay after all these years – it’s time to let the next generation enjoy something joyous. After all, if Peep Show taught us anything, it was not to listen to Super Hans.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News