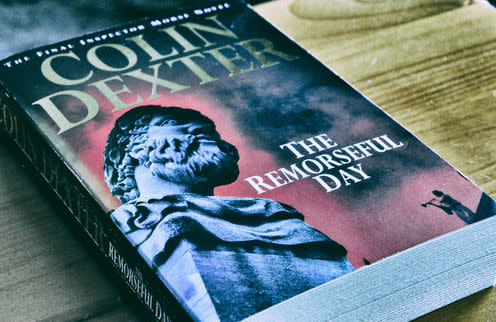

Colin Dexter 1930-2017: Morse novels a clue to the depth of writer's intellect

Colin Dexter’s death at the age of 86 has revived the debate about “serious” versus “genre” novelists. Newspaper tributes rightly referred to the creator of Inspector Morse as a “crime writer” – and so he was. But the sophistication of his novels, like those of John le Carre or Patrick O'Brien, mounts a strong argument for the proposition that pigeonholing their work simply as “detective” or “spy” or “historical” fiction is to diminish their value.

Dexter’s writing draws frequently on literary and other arts – and it should be particularly valued for its complex and nuanced representations of the merits and pitfalls of education and high culture.

First published during the Thatcher years, Dexter’s novels speak with renewed force to my concerns about recent negative representations of intellect, education and the academy in media and society. In the past year alone, academics in the UK and US, for example, have been painted as threateningly left-wing, liberal (in the US), silly, idiotic, and irrational.

They’ve been accused of trampling on freedom of speech and, by the US education secretary Betsy de Vos, of brainwashing students – as well as epitomising self-righteousness and entitlement.

Dreaming spires

Dexter’s Oxford, which is the backdrop for Morse’s adventures, is the most enduring fictional representation of a UK university – perhaps any UK educational institution. It includes depictions of town as well as gown, and balances an idyllic surface by plumbing the murky depths of elitism and corruption.

In his own words, Dexter created Morse because of his perception that in 1970s British readers and viewers were “fed up” of American hard-boiled crime fiction – “people running up and down corridors” – and endless “car chases”, saying: “What we want is a bit more brains and a bit less brawn.” The actor Kevin Whately, who played Morse’s sergeant Robbie Lewis, has spoken of Dexter’s obsession with “alpha-brains” – the superior intellect with which he imbued his detective protagonist.

Morse never graduated from his Oxford undergraduate degree, but is ferociously agile at crosswords and passionate about opera. His uncertified intelligence in the novels is pivotal to his success as a detective – Morse has the knowledge and ability to match the Oxford dons and high-flying students he encounters (often finishing off quotations for them, to their surprise and chagrin). Meanwhile his outsider status allows him to investigate unhampered by the old boys’ network.

Although Dexter’s writing celebrates lively intellects and culture vultures, with or without the trappings of academic qualifications or wholly rarefied lifestyles, it also paints Morse as a bit of an intellectual snob himself, despite facing prejudice from the Oxford establishment that he failed to join when he dropped out of university. Dexter also slyly celebrates Lewis’s vast, up-to-date knowledge of popular culture, which invaluably complements his boss’s academic and cultural sophistication when it comes to solving puzzles.

Formative influences

Dexter’s ability to convincingly represent different perspectives on intellect and education arguably stems not just from his life experiences but, more importantly, his own attitudes towards them. Dexter grew up in the East Midlands and declared that his family owned only three books. He and his brother trained to be Classics and English teachers. As a result – and unlike Shakespeare, whom he conventionally termed “the greatest writer in English” – Dexter could certainly not be accused of having “small Latin and less Greek”. Meanwhile Dexter once described his brother as becoming a talented pianist and violist, with a penchant for Wagner – a trait instantly recognisable in Morse.

In a late 2015 interview with Susan Smith, a postgraduate researcher at the University of Birmingham, he paid tribute to his school English teacher – the aptly-named Mr Sharp – who made it his mission to guide the teenage Dexter through his “ignorance of English literature” and the entire canon of Thomas Hardy.

Dexter was particularly fond of the teaching tradition of learning passages of poetry and phrases from drama by heart. He used them consciously and unconsciously in writing and apparently penned them from memory, rather than searching for his allusions in books.

He also emphasised the difficulty readers today face in getting Shakespeare’s historical references and believed that the sounds of Shakespearean lines could be more accessibly pleasurable and valuable than what they actually meant. If this was a veiled attack on test-driven education, it is an interesting one given Dexter’s work for the University of Oxford’s local exam board, a body which designed and awarded vocational qualifications. Meanwhile, the emphasis on the sound of words is poignant given that the onset of deafness was the impetus for this first career move away from teaching.

Killing off experts

The “death of the expert” has often been announced in recent months, and alongside it a more widespread anti-intellectualism bemoaned. Dexter’s whodunnits and their descendants are saturated not just with erudite characters with wide-ranging specialisms, high cultural works and events (opera, classical music, literary festivals). They also exhibit an everyday joy in mental exercise given Morse’s fondness for crosswords, anagrams, and arithmetic.

Indeed, his works constitute opportunities for readers’ and viewers’ mental puzzling, including spotting Dexter in his Hitchcock-style cameos as well as his mischievous deliberate errors and made up quotations. Their popularity, still airing in prime-time slots on various, commercial, free-to-air channels, after over half a century, goes someway towards counterbalancing moral panic about alleged social apathy – even hostility – to intellect, education and the academy.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Sarah Olive does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News