'Colourful, vibrant, sensual!' Stars on Jimi Hendrix, 50 years gone

Johnny Echols, Love

I first met Jimi – he was called Jimmy James then – at the California Club in Los Angeles. He was down on his luck at the time. His wardrobe was shabby and he reeked of Right Guard deodorant, which he used in copious amounts because he couldn’t afford to have his clothing properly dry cleaned. The heels on his shoes were so worn down he appeared to walk bowlegged. When Jimi sat in with us, he was a mediocre guitar player, at best, who was constantly out of tune.

A couple of years later, [Love frontman] Arthur Lee and I drove past the Whisky a Go Go in Hollywood, and there was the name Jimi Hendrix. We dropped by later that night, and Jimmy James had somehow morphed into a guitar god. I have no clue how he became so impressive in such a short period of time. The metamorphosis was simply astonishing. Later, after we became friends, I would often joke with him by asking if he had made a trip to the crossroads, à la Robert Johnson.

I heard the news of his death from Arthur before it became public. It was sad, even shocking, but not surprising. He had been living on the edge for quite a while. In the final analysis, living legends often don’t live very long.

Betty Davis

Jimi was very colourful. Very vibrant. He was electric – not just in his sound. He felt things on a deep, deep level. And he was like me, an introvert – he was an extrovert on stage and in his style, but Jimi was very quiet. He wasn’t a big partier. He was very, very sensitive, and also very sensual. My favourite song is Foxy Lady: it’s such a great way to describe a woman.

I used to play Jimi really loud all the time in our apartment, so that’s how Miles Davis was introduced to his music, just like I introduced him to Sly and Otis Redding. I remember I had Jimi and some people over our apartment for a Moroccan meal. Miles wasn’t able to be there because he was working at a club. So, Miles called, and he said: “Put Jimi on the phone.” And Miles asked him to go over to the piano and read the sheet music and tell him what he thought. And Jimi said: “I can’t read music.” The fact that Jimi couldn’t read music, and he was that rhythmic, really impressed Miles. His understanding of what a musician was changed when he met Jimi.

Dave Mason, Traffic

I can’t remember which club it was, but I went there just to hang out and get a drink. There was normally some band playing – a folk band or something. But suddenly some lanky, skinny guy with this big Bob Dylan electric hairdo gets up on stage. He’s wearing a pair of jeans and a Levi’s jacket. And that was the first time I saw Hendrix. I thought: “Oh my God, maybe I should look for another instrument.”

I played the acoustic guitar part on All Along the Watchtower, and I sang on Crosstown Traffic – there were three or four other tracks where I played bass and sitar, but I’m not exactly sure what happened to them. I didn’t know Watchtower was gonna be as special as it was – I assumed that anything he did would be pretty special. There was nobody like him and there still isn’t anybody like him. I mean, there are some great guitar players out there, don’t get me wrong. But there are no more Jimi Hendrixes.

And when he was recording – which was most of the time I was with him – he was all business. Jimi wasn’t screwed up in the studio. He wasn’t high. He was all about getting things done. To single one person out like Jimi on the drug thing ... I mean, did he make a mistake that night and take the wrong stuff? At some point, obviously so. But this could have happened to anybody. For God’s sake, everybody was on drugs.

Hannah Findlay, Stonefield

There aren’t really a lot of guitar heroes around these days, but we’re still talking about Hendrix. And I guess his death probably does affect how I see him. In a way, it’s almost the highlight of his life: that he made it all happen in such a short period of time.

Steve Howe, Yes

Prog was all about the sponge. What would Stravinsky do here? What about Count Basie? What would Hendrix add to it? We were always mixing up our arrangements into a conglomerate, if you like. It was about freedom, having no holds barred. That’s why I got into music in the first place. For that one word: freedom, and that’s exactly what Hendrix represents.

Kurt Vile

I got into Hendrix as a kid, walking down the shore and listening to my 90s Discman. Especially Castles Made of Sand. That reverse guitar going round your head, the way the tracks bled into each other: it’s a wall of noise that still has such an effortless, soulful groove. I remember being a stoned teenager for the first time and hearing EXP, the intro track to Axis: Bold As Love. I think we had four speakers arranged, and the weird, sped-up English broadcaster and all the feedback were literally spinning around our heads. Man.

I could never try to play as well as Jimi. But he always has that soulful thing going on: moving in and out of noise and into melodic figures, and back to noise. He was definitely the first of the classic rock guys I got in those formative years.

I’ll tell you this. Neil Young is still with us, and still plays with that soulful feeling. He has it. Jimi had it. And the only thing you can see on Neil’s guitar strap is a picture of Hendrix. That tells you something.

Joey Walker, King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard

Machine Gun, the Band of Gypsys version, might be one of my favourite songs of all time. You can never quantify Machine Gun. Every time I listen to it, that entry into the solo where he holds that note for 30 seconds or whatever it is, that still just hits me now. Even thinking about that, I’m getting hit up by it.

His sense of rhythm is unbelievable, and maybe not as recognised as it should be. In Gizz, we do have solos, but they’re not lairy – I feel like rhythm is a real intensely important element to our playing. And Hendrix comes through in that way. Hendrix is obviously one of the greatest of all time, but he was technical without ever being boring. He worked within constraints that weren’t hugely advanced in what would be considered guitar maestro, on a theory level. So that’s inspiring to me. Because I know theory to an extent, but I don’t go psycho with it.

John McLaughlin, guitarist with Miles Davis and Mahavishnu Orchestra

I know it might sound strange, but I’d compare Jimi’s playing to the later recordings of John Coltrane – things like Intergalactic Space or Om. Trane was going for two or three notes at a time and distorting his saxophone – the harmonics come out and the note is fatter, more robust. And Jimi was amazing at this, at the tone.

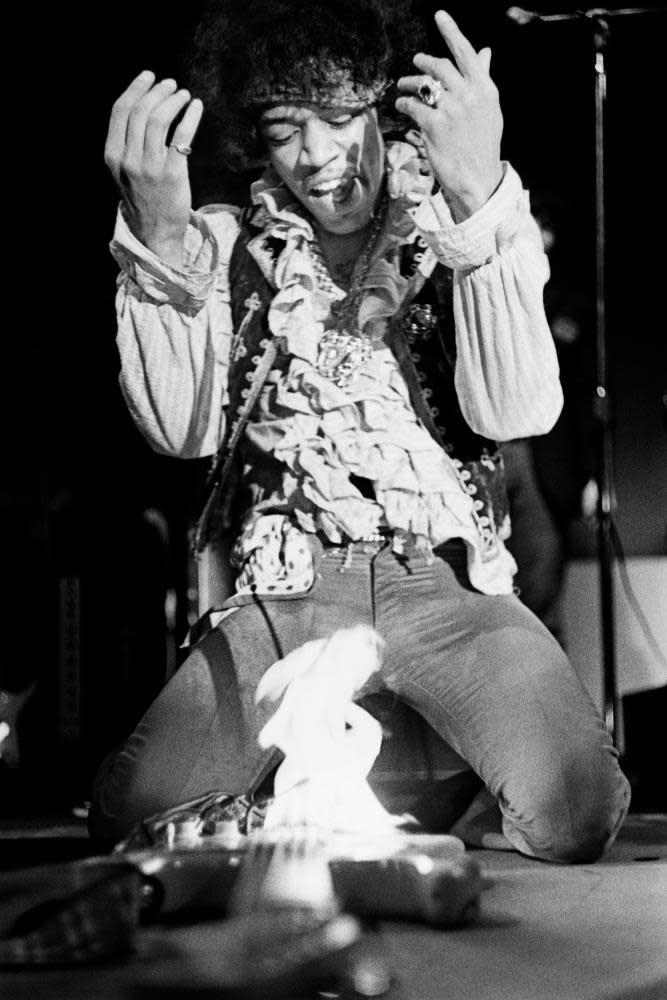

I was at Miles Davis’s house one day, and he told me he’d never seen Jimi play. So I took him to one of the arts theatres downtown, where they were showing the 1967 film Monterey Pop, which has the famous scene of Jimi setting his guitar on fire. All the way through Jimi’s performance, all I heard was Miles talking. “Damn! Damn, Jimi!”

For me, the idea of the best is something to do with sport. Winning. It doesn’t really apply in music. It’s what gets you. It’s what grabs you by the intestines and the heart and the mind all at the same time. The few who do that, they’re the greats. Jimi was one of them.

Joey Santiago, Pixies

When I first heard him play guitar, it was amazing. They were showing Woodstock on TV, and Hendrix did the Star Spangled Banner. His guitar seemed to be like an extension of his body – it’s a part of his arm. I was blown away at how he made the guitar sound, like Vietnam, like jets fucking attacking bullshit. You know? One that I later got blown away by was Third Stone From the Sun: definitely drug-induced. I took acid because of him actually. You shouldn’t follow everything people do, but I did. And when he burnt his guitar at Monterey, that was pretty fucking cool for a kid.

Michael Rother, Neu!

I was 17 when he somehow fell from the stars. He was on a German TV show called Beat Club, and he played Hey Joe. My jaw must have dropped.

His guitar style, the way he liberated it using the whole studio, impressed me deeply. And I think it also had a pre-echo to the way I recorded Neu! with Conny Plank. The forward guitar, the backward guitar, the sideways flying guitars: they still move me because I have this – what do you call it, a knack or something? – for mystery in music.

He didn’t have much time to sit down and focus on where he was going. It was five or six years before my solo career took off, and even that was a challenge: suddenly being well off and selling a few hundred thousand copies. But, compared to artists like Jimi Hendrix, it’s nothing. How does one adapt to a totally new situation within hours, weeks, days? Psychologically this is a very tricky and demanding situation. I think it’s no wonder that so many musicians end up in that 27 club.

Peter Hayes, Black Rebel Motorcycle Club

There was a phase in high school when I was searching for something: home, a self, I guess. And then I discovered Jimi Hendrix. I started listening to his music constantly – anything and everything I could find at the time, on repeat, non-stop.

I had a few moments listening to his music on LSD. There was one moment I remember pretty distinctly, when nothing was really making sense but Hendrix. It was all chaotic, but he was very clear: the music, his voice, his picture.

There’s a freedom in Hendrix’s music. And a lot of the words he was talking still make sense. If 6 Was 9 was a favourite. “I’m the one that’s gonna have to die when it’s time for me to die” – that was a big statement at 16 for me [laughter].

Michael Hampton, Parliament-Funkadelic

I don’t think I can say I understand him – I’m not sure if you can ever get someone like Hendrix. I’m not sure if I even want to. When he gets really heavy or deep, maybe a little dark in some places, it makes me back up. I try and take whatever I can and get outta there. I don’t wanna be that good. Being on that level brings its own thing to the music. You feel like you have to play to that high every time – it brings competition, which can morph into jealousy, to the sound.

It can get overwhelming – to play on that level or beyond can take you out, for real. You go all out with your music and you lose sight of everything else happening around you at the same time. Too much one way or the other and you may even lose your creativity. Flying too close to the sun, that can melt your wings.

What he was talking about, together with the music, are on the spiritual level. His music is a church-type thing. You can’t put a label on it. It’s just music, notation and sound, and it brings people together in a very real way. And I guess being on that level can pose a lot of responsibility for a musician.

Playing like that gets you in the zone. You don’t know what’s coming next, and if you’re open to the guitar, it can become one with the person playing it. If you could feel that zone, too, you’d feel something like a spiritual experience, I suppose.

Will Carruthers, Spacemen 3 and Spiritualized

Jimi Hendrix was the greatest guitarist that ever lived. At least that’s what I’d heard. I went down to the record shop and looked through the sleeves, and found Axis: Bold As Love. And it looked very peculiar. From the greatest guitarist who ever lived, I was expecting pyrotechnics, but I found myself seduced by the ballads. I was expecting twiddly solos or something, but it was the subtlety of his playing and the lyricism and the poetry that got me in.

I moved to Birmingham and lived in an Irish pub. Somebody gave me a cassette of Electric Ladyland, and that’s the only music I had for about a year. I was working in a sheet metal factory, and there wasn’t much transcendental about it: it was brutally repetitive, boring work. After a shift, I’d go upstairs and put on Hendrix every night before I went to sleep. 1983 … (A Merman I Should Turn to Be) used to drift me off beautifully into the dreamworld, which was, I have to say, infinitely preferable to the real world. I know the album note-by-note. It’s woven into the fabric of my teenage, factory-working self.

Samantha Fish

Blues and rock’n’roll is all sexual. That’s been part of blues since the blues began. It’s just oozing with sexuality. And he did – that’s part of his draw.

Hendrix liked to make psychedelic things happen on stage and freak people out, too. I’m drawn to that. The most important thing about Hendrix was the voice he had and how he channelled it through his fingers. Innovation isn’t just about gadgets. I don’t care if he was running that shit clean through an amp – it would have been just as amazing, passionate and real. That’s what guitar playing is about.

I think the music industry is still fucked up, but just in a different way. You can’t show up and be as reckless as some of these rock stars of yesteryear – they won’t have it in business – but it’s still just as shady once you get past the substance and the craziness. Like Hendrix did, artists get taken advantage of and used up. I can’t say the business can kill people like it killed him then, but real problems still exist.

Eric Bell, Thin Lizzy

The first time I heard and saw Hendrix was on a little black and white TV in my home in Belfast. Hey Joe. The sound of the guitar got to me first, and then his relaxed confidence. And when he played the guitar solo with his teeth, guitar playing was never going to be the same again – we would all have to start practising more. In Thin Lizzy, Jimi was incredibly influential to Philip [Lynott, frontman], who saw a black man up there having a rare talent and showmanship, leading the parade and all of us following him. It gave Philip confidence in himself.

Shana Cleveland, La Luz

I found Axis: Bold As Love and Are You Experienced? in my mom’s record collection when I was 14. I listened to them every day for a couple of years. They’re dreamy and wild, and that’s how I felt all the time as a teen, so it made sense.

I remember taking a Hendrix CD to school one day and playing it in class, and some of the other black kids were kind of laughing at it, thinking it was lame, whatever. And when I showed them his picture they couldn’t believe it. They thought it was so weird that this black guy was playing rock’n’roll, playing guitar like that. Kids were just really closed-minded about music back then, with these really fixed and narrow ideas of what “white music” and “black music” sounded like. Of course, black people invented rock’n’roll. But I didn’t know that then, so I couldn’t tell them.

He redefined the guitar so he will always matter. I read things about how the electric guitar is going out of style or whatever, but I don’t believe it. Maybe cheesy blues-lawyer shredders are rightfully going out of style, but real artistry isn’t diminished by time or the tide of trends.

Captain Sensible, the Damned

Fire is my favourite. It’s upbeat and raunchy. If the song had been released in the heyday of punk, it wouldn’t have sounded out of place. The lyric showcases Jimi’s cheeky sense of humour, too. I mean, “move over Rover and let Jimi take over” may well be about a dog hogging the heater on a cold day, but I’m putting my money on the bulk of it addressing a lady friend.

I only managed to get my head round a handful of Jimi’s guitar licks, but they’ve enabled me to bluff my way through 40 years of live work. His playing is so inventive, and that’s something the Damned always wanted to emulate. We stretched ourselves in the studio, even if it drove the engineer nuts.

Connan Mockasin

I first heard Hendrix in a Steven Seagal movie, Under Siege, when I was a kid in the early 90s. I put Band of Gypsys on to tape and just kept rewinding: finding little details and trying, trying to play it on guitar. It got me down a rabbit hole of Hendrix. He still affects me in nearly every way. I really enjoy bending, for example – guitar is such an expressive instrument, and bending just gets things flowing through it.

Will Sergeant, Echo and the Bunnymen

My favourite Hendrix song has to be Voodoo Child (Slight Return). It was the first record I ever bought: a seven-inch single for six shillings. He’d only recently died. When it kicks off in the middle, you just think, “How the fuck is he doing that?” It sounds like 10 guitars going off at once, but you can do it with one through volume. You can hear the hum on the amp in the whole track – which means, basically, that the volume was turned up fucking loud.

Extreme volume is an effect in itself. You can do things with it. You feel kind of superhuman. You can blast into a great big E chord and it just goes on for ever – it changes the air and the plasma in the room to make something else, almost from another dimension or something. But Hendrix hasn’t influenced me at all. It’s impossible. You can’t say that you’ve been influenced by him, because you can’t go anywhere near him. It’s cheeky to think that you’re even in the same world, let alone to mention him in the same breath.

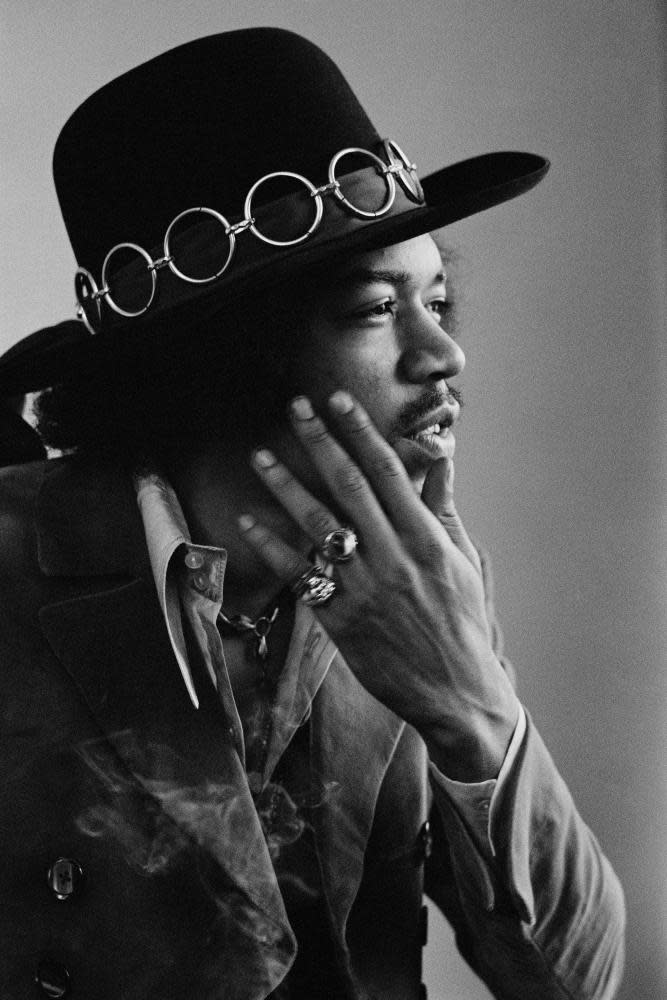

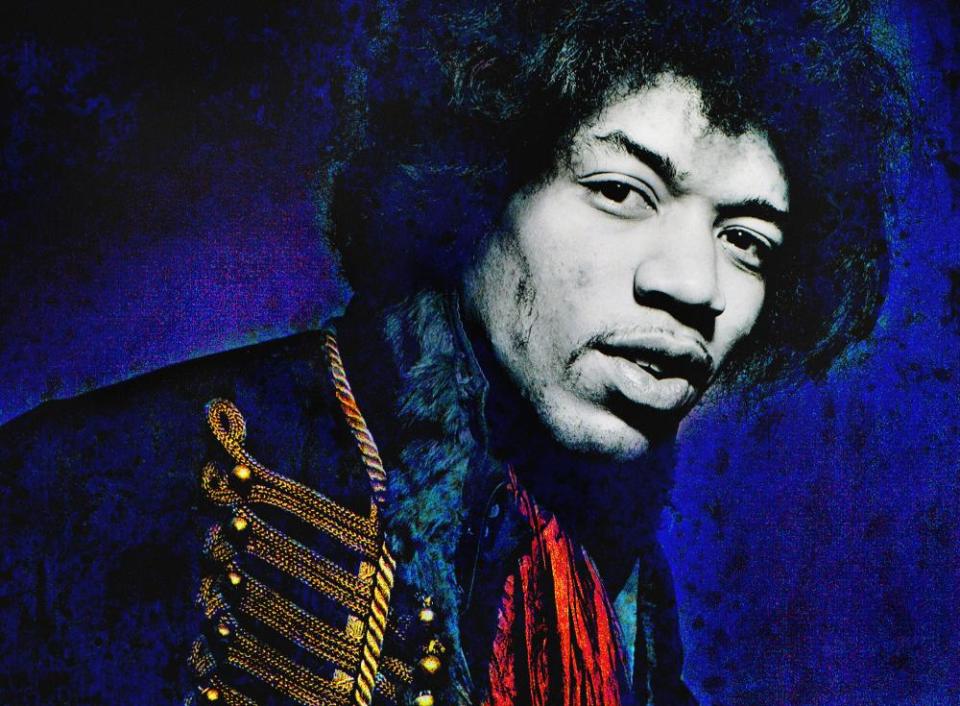

• Images courtesy of Masterpiece Art gallery, London, from the exhibition Bold As Love: Celebrating Hendrix, until 30 September.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News