Derek Williams, award-winning documentary maker whose films gave early warning of environmental crisis – obituary

Derek Williams, who has died aged 91, was a leading documentary filmmaker who made early films warning of the dangers to the environment of pollution and the car; he received four Baftas for his work and was nominated for four Academy Awards in the short films category.

Williams was born on August 20 1929, just across the Tyne from Jarrow. In the late 1930s his family moved to a suburb of Newcastle upon Tyne and he was educated at Newcastle Royal Grammar School, which was evacuated during the war to Penrith; his classmates included Brian Redhead, later presenter of the Today programme.

Derek became interested in cinema as a child, attending, via the Tyneside Film Society, documentaries by British filmmakers such as John Grierson, Paul Rotha, Harry Watt and Basil Wright, as well as foreign language features by Jean Renoir, Marcel Carné, Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica.

Following National Service in the Army, mainly spent in north German cities still devastated by wartime bombing, Williams went to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, to read History. There, while hitch-hiking in Italy during the long vac of 1950, he decided to dip his toe into amateur filmmaking with a documentary about Hadrian’s Wall.

Completed in 1951, it represented what Patrick Russell, on the British Film Institute website, described as Williams’s “calling card”, its combination of careful pictorial composition, literate commentary and melancholy romanticism foreshadowing much of his later work.

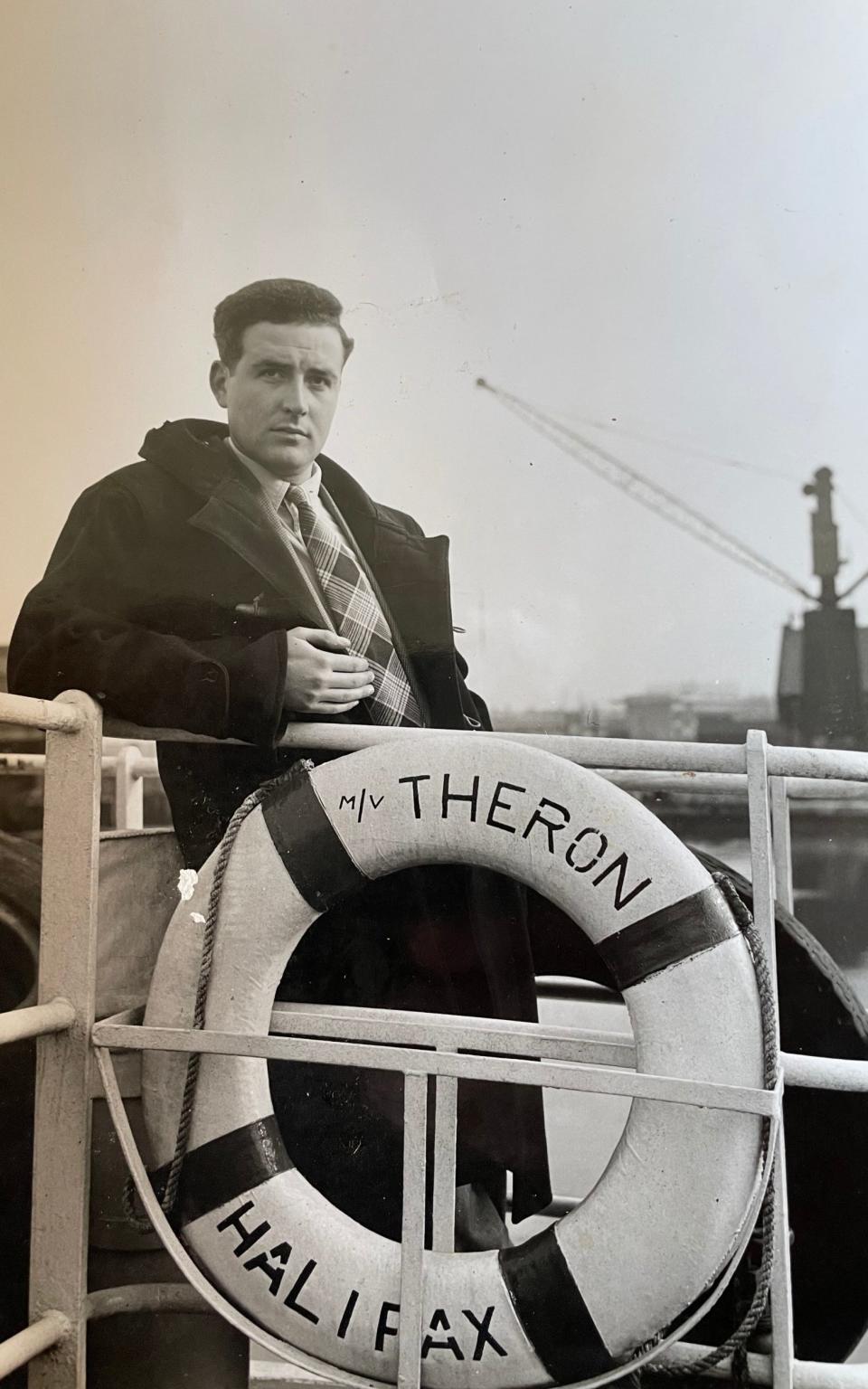

It landed him a job as a trainee assistant with World Wide Films, which gave him his first big break in 1955, when he was appointed to film the British Trans-Antarctic Expedition under Vivian Fuchs, sponsored by BP.

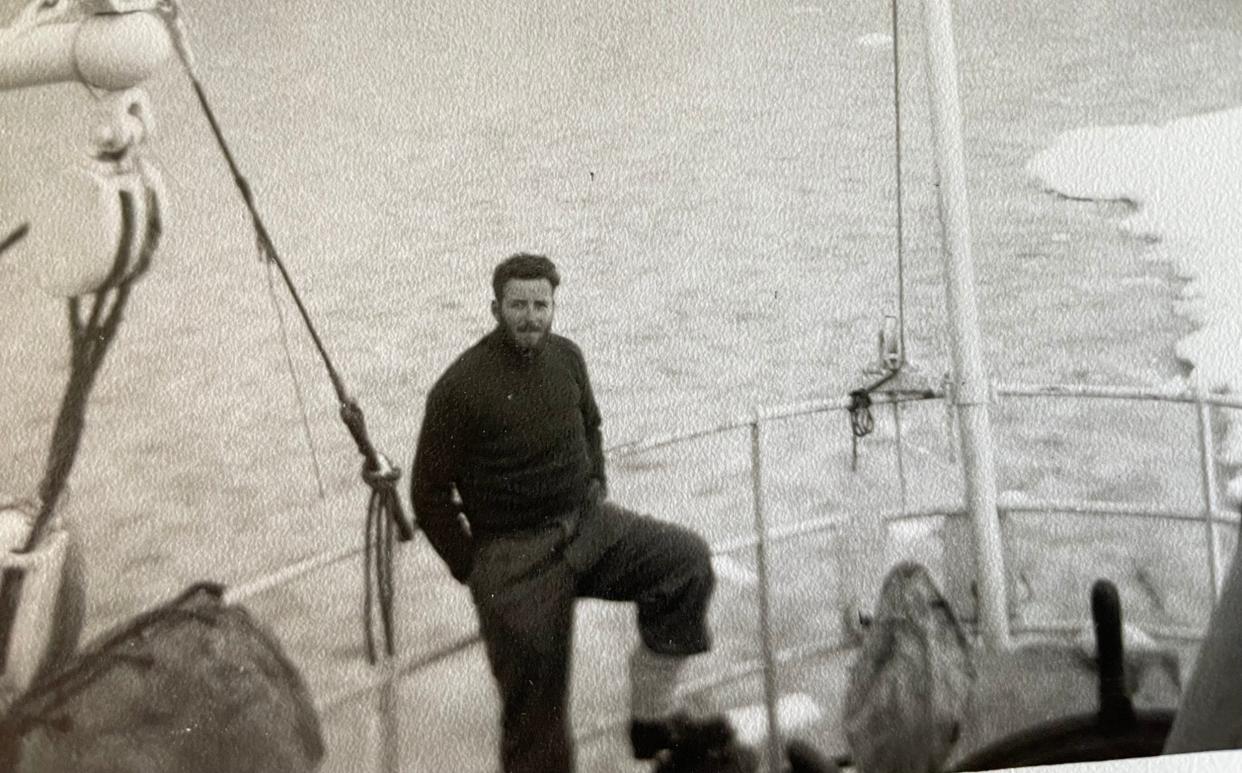

He became a member of the 16-person party that sailed to the Weddell Sea aboard the Canadian sealer Theron to establish an advance base for the main party due to arrive the following year. During the outward journey the ship became stuck in pack ice, sustaining considerable damage, and though after several weeks Theron was able to free herself, she had to depart more quickly than originally intended, having deposited the shore party who were to stay through the Antarctic winter, though Williams himself did not stay on.

The resulting film, Foothold on Antarctica (1956), received a private viewing at Buckingham Palace and went on to receive an Oscar nomination.

Williams subsequently moved to Greenpark Films, for whom he wrote and directed documentaries on a wide range of subjects, including There Was a Door (1957), about the care of the severely learning-disabled, which was televised by the BBC.

With Foothold on Antarctica having established him as a filmmaker willing to shoot in inhospitable conditions (and having established his credentials with the expedition sponsors, BP), he was later commissioned to accompany a team of BP-contracted Canadian oil prospectors to Alaska.

The resulting documentary, North Slope – Alaska (1964) was a heroic portrayal of man struggling to tame a hostile wilderness. But the acclaim which greeted its release died down as faith in industrial progress began to give way to environmental concerns, and in the years that followed Williams became involved in attempts by the oil company to renegotiate its relationship with the environment.

His The Shadow of Progress (1970), BP’s contribution to European Conservation Year, was a stark portrait of environmental crisis, featuring sobering images of rubbish-choked rivers, smog-covered cities, smoke-spewing chimneys and roads and cities teeming with cars. It won a galaxy of awards, though Williams later expressed regret that he had pulled his punches in the “solution” parts of the film so as to avoid any overt criticism of the sponsors.

On the strength of the film’s success, Williams persuaded BP to fund a sequel as a contribution to the 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment. The Tide of Traffic (1972) showed the mixed blessings of the internal combustion engine, with Williams’s commentary conveying his own dismay at the car’s effect on the urban environment. The film received an Oscar nomination and a Venice Golden Mercury.

The difficulties of satisfying sponsors while retaining intellectual integrity proved an issue during the making of Health of a City (1965), which Williams was commissioned to direct by Films of Scotland to mark the centenary of Glasgow’s appointment of its first Medical Officer of Health. Williams’s depiction of the grimmer aspects of Glasgow life did not go down well with the sponsors and he was not credited on the film’s release.

Patrick Russell reckoned Williams’s crowning achievement to be The Shetland Experience (1977), sponsored by the environmental advisory group of the Sullom Voe Association, a contemplative portrait of the Shetland Islands and an account of the environmental measures taken by the oil industry at the Sullom Voe Terminal. The film was nominated for an Oscar and Williams was able to attend the ceremony in Los Angeles for the first time.

Williams, who mostly worked freelance and continued directing until 1992, later found his career suffering due to the downturn in documentary sponsorship and declining audiences for film documentaries due to the growing power of television.

His last two films, A Stake in the Soil (1989) focusing on the exhaustion of soil by intensive farming, and Oman – Tracts of Time (1992), both sponsored by Shell, were largely limited to educational viewing, though the latter won the Chicago International Film Festival Award for best documentary.

In retirement Williams returned to his earlier interest in Roman history that had inspired his Hadrian’s Wall and went on to publish two well-received books: The Reach of Rome (1996) about the defensive system protecting the whole 4,000 mile imperial frontier, and Romans and Barbarians (1998), an account of relations with the tribal societies outside the frontier. He also appeared in television programmes on Roman topics.

In 2010 he was the subject of a retrospective at the British Film Institute.

In 1960 he married Olive Warren, who survives him with two sons.

Derek Williams, born August 20 1929, died August 2 2021

Yahoo News

Yahoo News